Funding freeze for Delaware's early learning 'Stars'

Listen 5:29At Babes on the Square child care center in Brandywine Hundred, 160 little stars spend their days in a nurturing learning environment.

The goal for the children, ages 6 weeks to 5 years, is to have them ready to thrive or excel by the time they reach kindergarten, director Andria Keating says.

“We are the base,” Keating said one recent morning while making her rounds at the sprawling center located in a suburban office park.

“We are the first people who engage with these children or the first people who are going to teach them how to take care of themselves, how to play with other children, how to follow directions. We begin the process of learning, of reading, and without the work that we do children start school not being prepared.”

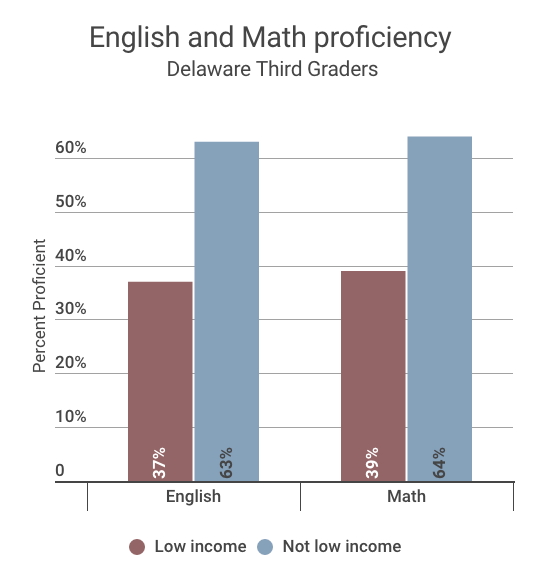

Educators consider early learning the most critical component to reducing the glaring achievement gap between low-income children and those of means.

For example, in third grade English, 37 percent of Delaware’s poor children are proficient, compared with 63 percent of children who aren’t low income.

In third grade math, 39 percent of low income students are up to speed, compared with 64 percent of children of means.

Those jarring statistics are burned into the mind of Logan Herring, who runs the Kingswood Community Center. The multipurpose complex is next door to Wilmington’s impoverished Riverside housing project, home to many of the families served by Kingswood’s child care center and other programs.

“If you can’t read you are not just struggling in English class,” Herring said. “You can’t read your math books. You can’t read your science books. You get frustrated. You start to act out. Everything starts in the early learning stages.”

To help cut the gap, Delaware pays most or all child care costs for poor parents who are working or going to school, a subsidy that last year cost taxpayers $70.4 million a year.

Centers who take low-income children also get additional subsidies under a program called Delaware Stars for Early Success. Monitored and evaluated by Department of Education officials, centers earn from one to five stars for the quality of their staff, curriculum and family engagement.

Extra state subsidies for Stars programs

Michelle Shaivitz, executive director of the Delaware Association for the Education of Young Children, a trade association for child care centers, said directors have embraced the nine-year-old Stars program to improve the quality of their programs.

“So the Star system was put into place so that we can improve the level of education our youngest citizens in Delaware get,” Shaivitz said.

She noted that the program is voluntary, “This is a center director or owner saying I want the best I can possibly give to my staff and the children we serve,” Shaivitz said.

Centers rated three or above receive so-called tiered reimbursements of up to $15 a day for every low-income child. The higher the ranking, the higher the subsidy. The state spent $20 million last year on the program.

Keating’s center has a four-star rating. The reimbursement she receives for her 55 children from poor families helps make ends meet.

“I get about $12,000 a month from the tiered reimbursement at a Star 4,” she said.

It goes to pay for the increased education of staff. It goes to pay for what benefits I can offer to staff. It goes to make sure that we have a high quality food program.”

Keating, whose center has its own kitchen and culinary staff, is now going for a Star 5 rating. That would bring another $4,000 a month.

Stars reimbursements frozen in place

But in September, Babes on The Square and the other 500 Stars centers received unsettling news.

Under Gov. John Carney’s shared sacrifice budget, they would not receive additional money by raising their Star level. The Carney administration and lawmakers also cut $26 million from K-12 education as part of plan to eliminate a projected general fund deficit of nearly $400 million.

Center directors had been buoyed by Carney’s claim that he planned to “maintain” investments in early childhood initiatives. But in late September, they officially learned what the administration had written into the state budget before it was passed by the General Assembly on July 3: that Stars programs could not increase their Star level, or the money that came with higher levels.

“There is not enough funding to expand Stars and tiered reimbursement in the 2018 fiscal year,” said a letter from Kimberly Krzanowski, who Carney appointed as director of the Department of Education’s Office of Early Learning in March.

‘Stunned’ directors now eyeing next budget

Shaivitz said state officials had assured them funding was going to be sustained— not frozen. Many child care leaders complained loudly at a subsequent public meeting.

“For some folks, this was the first time they were really hearing this information and they were quite stunned,” Shaivitz said.

“From the government perspective, when they shared that information they said there’s a lot of different organizations that have been cut completely.”

Officials told directors that “we’re not cutting anything. We’re sustaining you at this level,” Shaivitz said. “But when you are a person losing $50,000 a year then that word sustain means nothing to you, not for all the work you’ve done.

In an interview with WHYY, Krzanowski said that despite the freeze, the state remains committed to Stars participants. The state did relent somewhat and allow centers to pursue and earn higher ratings, albeit without the additional money this fiscal year.

“Although we’ve had a very tough budget year we’ve still been able to recognize programs and still provide them with their current tiered reimbursement levels,” Krzanowski said.

Child care centers are now preparing to lobby state officials and lawmakers to unfreeze the payments for fiscal year 2019, which begins in July. On their side is Krzanowski, a Carney appointee.

“I’m hoping that next year we are in a situation where growth can happen for Star programs and that the investment will continue,” she said.

“Some will say that without higher-level tiered reimbursement, they can’t offer the same services to these children and families. And that impacts our community. It impacts children coming into kindergarten. It impacts third-grade reading level.”

But even without the financial bonus, directors say they will continue the hard work of teaching the littlest learners, especially the neediest.

“They will run our economy someday,” Keating said, stressing that children who get quality early education are likely to do better in school and life.

“They don’t have to go to jail. They don’t have to have services in high school because they’re not prepared. Their health will be better because they have been taught how to take care of themselves. What we do right now changes the entire outlook of our state.”

Herring echoed other advocates in saying that one of the best investments parents and the government can make is toward educating children as soon as possible.

“If we don’t address this need, address it in a consistent manner,” he said, “we’re going to be struggling for a long time.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.