For the sake of boredom: Finding comfort in doing less

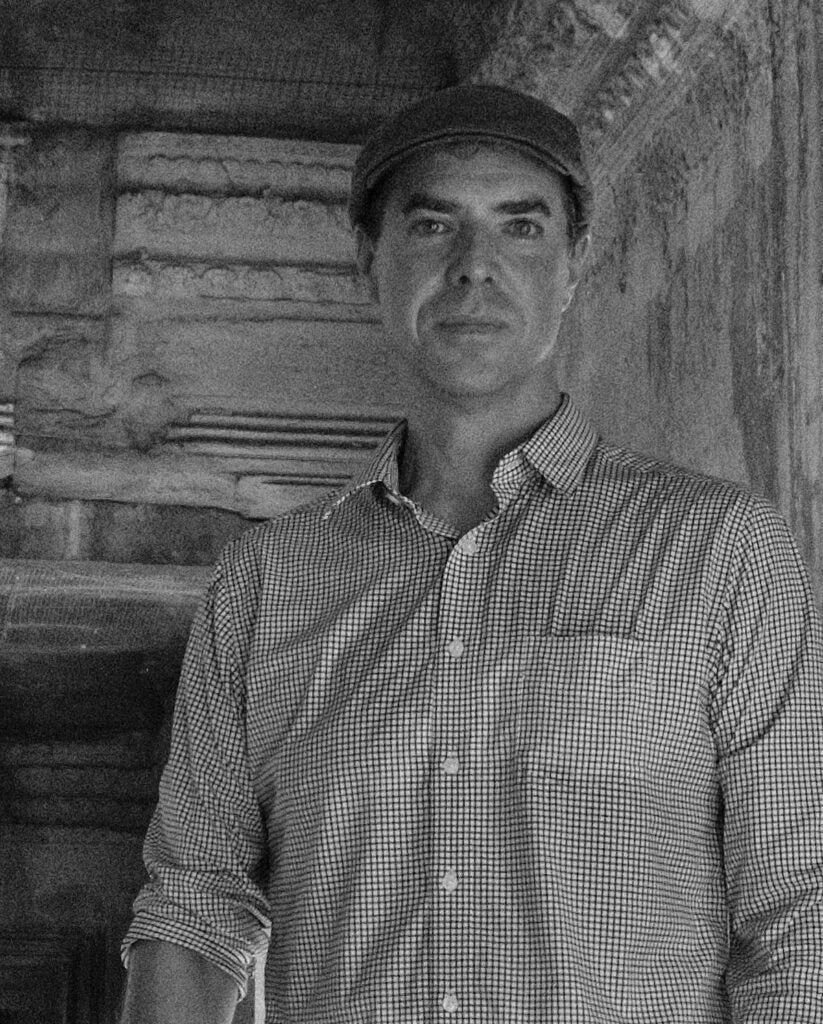

UPenn religious studies professor Justin McDaniel shares his take on boredom and the insights he learned from his time as a monk.

Listen 7:17

Justin McDaniel during his time as a Buddhist Monk in Thailand. (Courtesy of Justin McDaniel)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

In “Anna Karenina,” Russian writer Leo Tolstoy once described boredom as a “desire for desires,” a restless commotion arising out of not knowing what to do.

For linguist Justin McDaniel, boredom means something much more literal:

“To bore a hole in something. Meaning that you are pierced, you’re rendered frozen, and then you’re emptied out,” he described. “It’s like a beginning.”

That new beginning started for McDaniel when he traveled to Thailand in his early 20s, expecting to volunteer and teach English. Instead, he became a monk in a remote Buddhist monastery on an island between Thailand and Laos.

“The closest thing to monastic life is military life or prison,” McDaniel said. “You have to do a lot of these tasks that go against your instincts, go against protein, go against procreation because you’re celibate.

“In my monastery we had 243 rules — from the way you speak to how you go to the bathroom, how you walk, every movement you make,” McDaniel said. “The one thing that is not captured is your mind.”

It was a simple life with very few choices and a lot of chores that had to be done every day.

“Tomorrow, you have to sweep the path again,” he said. “There’s going to be dust on the Buddha statue; you polish it again. It just seems endless.”

But for McDaniel, there was a lot of beauty in those simple tasks.

Subscribe to The Pulse

“There’s something very liberating in that doing these series of tasks allows me to concentrate on them and breathe; pay hyper attention.”

McDaniel adjusted well to monastic life. He wasn’t bothered by the routines, the strict rules, or how little food they usually ate — just about 800 calories a day. So eventually, he decided to try something more extreme: seven days of fasting in complete solitude.

“[I was] placed in this wooden box in the middle of the jungle,” he said. “There’s no light, I was bent over, seated in a half lotus position. You can’t stretch your legs. And then you would have a straw come in through a hole twice a day to sip some water.”

McDaniel remembers being extremely uncomfortable. It was hot and his hunger was brutal. After about three days, he started hallucinating.

“There was a benefit, at least for the first three days, of really feeling your body,” he said. On the seventh day, he fell out of the box and the other monks had to carry him back to the monastery. It took him a week to recover.

“It was dangerous, and I shouldn’t have done it,” McDaniel said. “But I was kind of a hothead. I just like challenges.”

The lessons from McDaniel’s time as a monk stuck with him and today, he’s well known for bringing them into the classroom at the University of Pennsylvania. For 22 years, the religious studies professor has been teaching a radical course on comparative monasticism called Living Deliberately in which students have to take a vow of silence for a month. No speaking, no gesturing, no phone, and no internet are just a few of the restrictions in the course.

He also teaches a course called Existential Despair where students gather on Monday evenings and read a book cover to cover. They read authors like William Burroughs and Yukio Mishima — writers who grappled with life often on the fringes of society. The course is notorious for pushing many out of their comfort zones, but that’s part of the point.

“I want my students to, just like I did as a monk, learn to appreciate the task that’s in front of them, the words that are in front of them, the desk that’s in front of them, and then the person that is sitting next to them,” McDaniel said. “Slow down and pay attention to the room.”

“We’re encouraged that if you want to be creative, take this pill or take a class or do yoga or do SoulCycle or talk to a therapist, which are all great things,” he said. “But these are just adding, adding, adding. If you look at what monks and nuns do, they don’t add more, they do less — less speaking, less choice of clothing, less choice of food, less choice of activities. A monk’s day is very boring to most people. However, it makes you reevaluate your every day and see that it is not boring. Gravity is not boring if you actually feel it. Breathing is not boring. Just sit there and try to fill up your lungs to the greatest capacity possible until your chest is straining. It is incredibly interesting to see how the body works.”

McDaniel wants students to learn how to feel at ease with boredom, with the lack of input, and to just exist in their bodies. Rather than antagonizing boredom or apathy, he believes these states signal a much-needed resting state for our brains.

“It’s interesting how our brains crave nothingness. And we do this all the time. Like we go listen to music or we go to a museum. But we try to act as if it’s about learning or productivity when it’s really about our brains needing a pause.”

‘How to be comfortable with ourselves’

McDaniel’s cousin Simon Fitzmaurice was an Irish filmmaker who spent the last years of his life living with ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a rare neurodegenerative disease that progressively causes paralysis. Watching his cousin live through the condition reinforced how he viewed the power of boredom.

“For the last three years of his life he was completely frozen,” said McDaniel. “So, he was bored all the time and he would talk about this. ‘I have to wait for everything. I have to wait for somebody to change my breathing machine. I have to wait for food. I have to wait for my children to be put in front of me because I can’t turn to see them.’ And the power of his mind; the beauty of his words, that he couldn’t even speak, was so impressive.”

Fitzmaurice wrote a memoir, “It’s Not Dark Yet,” and directed a feature film, “My Name is Emily,” while living with ALS. Despite his creative feats, the trait that impressed McDaniel the most was not his cousin’s ability to turn boredom into productivity — but his ability “to be comfortable.”

Simon Fitzmaurice died on October 26, 2017 in Dublin, Ireland.

“Our job is simply to learn how to be comfortable with ourselves,” McDaniel said. “Even if it’s just a few moments a day – learning how to read a novel for just the sake of reading it, learning how to read a poem for the sake of reading it, learning how to walk for sake of walking, wait for the sake of waiting, play music for the sake of music. Not for being good at it, not for practicing, not for showing off. But for stopping yourself; for freezing yourself; and putting a hole in yourself.

“The everyday is so spectacular,” McDaniel said. “And I think that if you can be comfortable with not knowing; if you can be comfortable with lack of productivity; if you can be comfortable with the wonder of the everyday around you, you’re going to be more empathetic to the person next to you in that they’re part of that wonderment.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.