Equipping police with a life-saving drug

Listen-

-

-

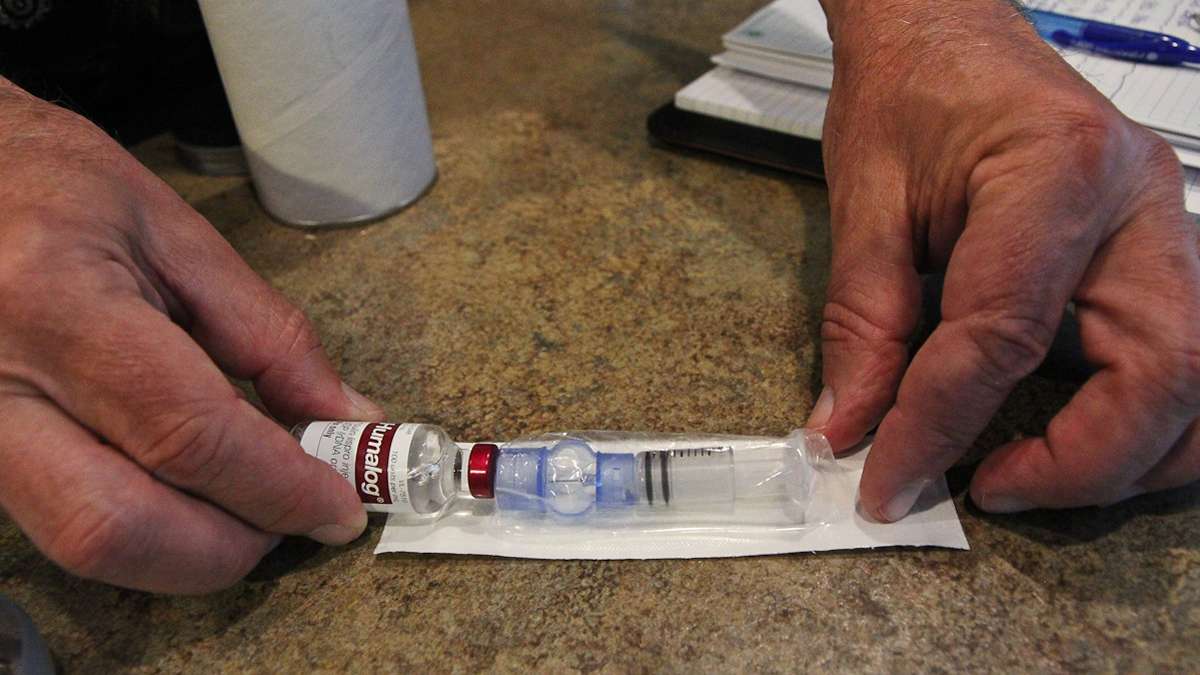

Randy Childress says management at his last job had a hard time understanding that he needed to take time during the work day to have snacks and inject insulin. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Overdose deaths from heroin have been rising all over the country, but some police officers now have a tool that could help prevent those deaths.

People are overdosing on heroin and prescription drugs across the region, including in quiet picturesque neighborhoods. Now police officers are pushing to get a tool that can help them save lives.

A few months ago, Denise Issacson walked out of her house in a quiet suburban Pennsylvania neighborhood and found her 21-year-old daughter in the driveway.

“It was traumatic seeing my daughter laying on the ground unresponsive. I think my heart stopped beating,” she said.

Issacson lives in Bensalem on a street where American flags fly in front of homes and the sound of birds chirping is the only noise in the neighborhood. It is peaceful and calm.

That sense of safety was broken on the night Issacson’s daughter injected heroin for the first time.

“I literally was on top of her, pounding her, trying to get her to talk to me. I was screaming her name. I don’t even remember. I think I was screaming, ‘What do I do? What do I do?’ I was just screaming.”

Issacson waited for help to arrive. The police got there. Still, she waited…hoping someone would bring her daughter back to her.

Finally, Issacson says, after what felt like hours, the paramedics arrived and gave her daughter the anti-opiate drug naloxone. The drug is perhaps better known by the brand name “Narcan” and it can be injected via syringe, or nasal spray.

Susan Shoemaker is outreach director at Steps To Recovery, a nationwide treatment provider that’s located in Pennsylvania.

“If paramedics did not arrive that night, we don’t know if she would be here today. Or if they hadn’t arrived in time.”

Coming back to life

In those dark moments when a person has overdosed on heroin or other opiates, Narcan can bring them back to life. Issacson’s daughter survived and is getting addiction treatment.

Lower Makefield Township Police Chief Kenneth Coluzzi knows things could have turned out much worse.

“We had somewhere in the area of sixty overdoses in Bucks County alone since the beginning of the year with about six deaths. So you can see one death’s too many – you can see the numbers are high and I don’t expect them to go down anytime soon.”

Chief Coluzzi said for his cops, arriving on the scene of an overdose can be frustrating. They’re not allowed to carry the life-saving drug, they have to wait for paramedics to arrive and administer it.

“That can seem forever for a police officer who’s standing there, especially when family’s lookin on and you know demanding that the officer do something to help and he’s just helpless.”

Coluzzi’s affluent swath of Bucks County is a world away from impoverished, crime-ridden Camden. But they share a common problem: drug use. Coluzzi’s cops, in Pennsylvania, don’t have the Narcan that’s available to his counterparts elsewhere, including in New Jersey.

Pennsylvania cops envy New Jersey counterparts

Just across the river in New Jersey, police aren’t so helpless. In June, the Garden State expanded a pilot program — putting Narcan in the hands of police. Officers in Camden have been quick to put the anti-opiate to use.

It was a May morning around 9 a.m. and Officer Edwin Cortez — a rookie cop — was on patrol.

“It was probably about here I heard the screaming but I didn’t know where it was coming from. And about right here’s where I stopped my car.”

Cortez pulled up to 6th and Cherry Streets in Camden and a man started hobbling toward him.

“He was like, ‘I’m having a hard time breathing. I’m feel like I’m dying,'” Cortez recalled.

The man had used heroin. The rookie cop grabbed a dose of Narcan from his car and administered the drug via a nasal spray. Cortez was the first Camden police officer to save a life by administering Narcan.

Camden County Police Chief Scott Thomson is glad his officers have the drug.

“When you’re dealing with the overdose issue, every second counts,” he said.

New Jersey Governor Chris Christie also supports the use of the drug.

“Treatment is impossible for someone who’s died,” he said. “It’s an obvious statement, but it’s true.”

Access to a life-saving drug

New Jersey isn’t alone, says the Network for Public Health Law’s Deputy Director Corey Davis.

“Law enforcement officers are carrying naloxone in at least 15 states including Ohio, California, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Georgia and New York.”

The Obama administration has called for law enforcement officials across the U.S. to carry the life-saving drug, saying drug addiction is a disease that can be treated and that the country can not arrest its way out of its drug problem.

There is opposition. Critics wonder if easier access to NARCAN will embolden users not to fear OD’ing.

But Davis says there’s no proof that happens.

“I know of no evidence that equipping officers with naloxone increases or decreases drug use. But there is evidence that naloxone access reduces overdose deaths, and one study showed that a naloxone training program reduced drug use among heroin users.”

Rich Roberts, with the International Union of Police Associations, worries whether officers will receive sufficient training to recognize an overdose and on how to administer the drug.

Lower Makefield Township Police Chief Kenneth Coluzzi understands the concern, but said he wants his officers to have the life-saving drug on hand.

“I think it’s something new and it’s scary to people and you don’t wanna do any harm,” he said. “But it’s relatively simple and we’ve had demonstrations on Narcan and especially the nasal form is very easy to administer, very safe.”

Chief Coluzzi is backing legislation now in Harrisburg that would give Pennsylvania police and EMTs the ability to carry Narcan.

The author of the Pennsylvania legislation has a personal motivation. State Representative Gene DiGirolamo’s son almost died from an overdose.

“I suffered in my family with a son who was a heroin addict for five years,” he said. “And I wanna tell ya my friends, it is the worst experience that you can possibly have – having a son or daughter who is addicted to drugs. It is a living hell.”

DiGirolamo said the ability to administer the drug via a nasal spray – as opposed to by syringe – is a ‘game changer:’ training is easy. It is afterall a nasal spray that’s administered like common allergy medication. And by bringing a person back from an overdose he said, there’s the opportunity for that person to get treatment and go on to lead a clean, productive life — like his son.

Some critics worry about requiring police to administer the drug, but DiGirolamo said the legislation isn’t a mandate – it simply gives police permission to carry the drug and use it.

Isn’t Police Chief Coluzzi worried that the additional ‘tool’ might be adding more work and asking police to do too much? Without a pause, Coluzzi said, not at all.

“We can’t make a decision on who lives and who dies, and when a police officer arrives on the scene, that’s his job,” he said. “And that’s what he did when he rose his hand and took the oath.”

Since late May, Camden police have saved more than a dozen people who were overdosing — by administering Narcan.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.