Does pretty hurt? A look at the health risks of hair dyes

Coloring is a complex chemical reaction, a sophisticated organic synthesis, that takes place in each strand on the top of your head.

Listen 11:09

Because beauty products are not heavily regulated in the U.S., there is some concern about the unknown health risks of hair dyes. (Image courtesy of Gerain0812/Bigstock.com)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

It was when she first started beauty school, in 1999, that Michele Ortiz first noticed unusual things happening to her body. The symptoms started out as allergy sensations.

“I was getting skin irritations and breakouts all over my hands, itchy eyes,” said Ortiz, who lives in Santa Barbara, California.

After beauty school, Ortiz started working as a hair colorist. And gradually, things got worse. She started to feel chronic fatigue, nausea and achy joints. She had trouble with temperature regulation.

“I was experiencing bouts of uncontrollable heat in my body throughout the day and at night. Very, very uncomfortable, and definitely caused some depression as well,” she said.

Butterfly rashes erupted across her cheeks. She felt sick and light-headed when she was under the sun. Her whole body hurt.

“It was a struggle to walk upstairs,” she said. “I was just in pain a lot.”

For a while, Ortiz felt really lost. She didn’t want to confront the possibility that her job was making her sick, because she loved her work — enjoyed making the formulas for different colors and the craft of applying the dye.

But she was in her 20s, and should have been at the top of her health.

“I was thinking, ‘Well, maybe I’m just having stress and anxiety,’” Ortiz said. “I kind of felt crazy, like something was wrong with me.”

Here’s the thing: Maybe Ortiz wasn’t so crazy. There are thousands of chemicals used in hair dyes, and their impact on our health is often unknown, or of concern.

Because personal-care and beauty products are not heavily regulated in the United States, some researchers and advocates fear that hair dyes can be harmful, especially for people like Ortiz, who are exposed all the time.

What are the health risks of coloring your hair? To make sense of it, it’s first helpful to understand how hair dye works.

What’s happening chemically when you dye?

You might not think of it when you’re in the salon, but hair dyeing is a complex chemical reaction, unfolding within each strand of your hair.

“You are basically doing a very sophisticated organic synthesis, right on top of your head,” Jiaxing Huang, a professor of material science and engineering at Northwestern University, said.

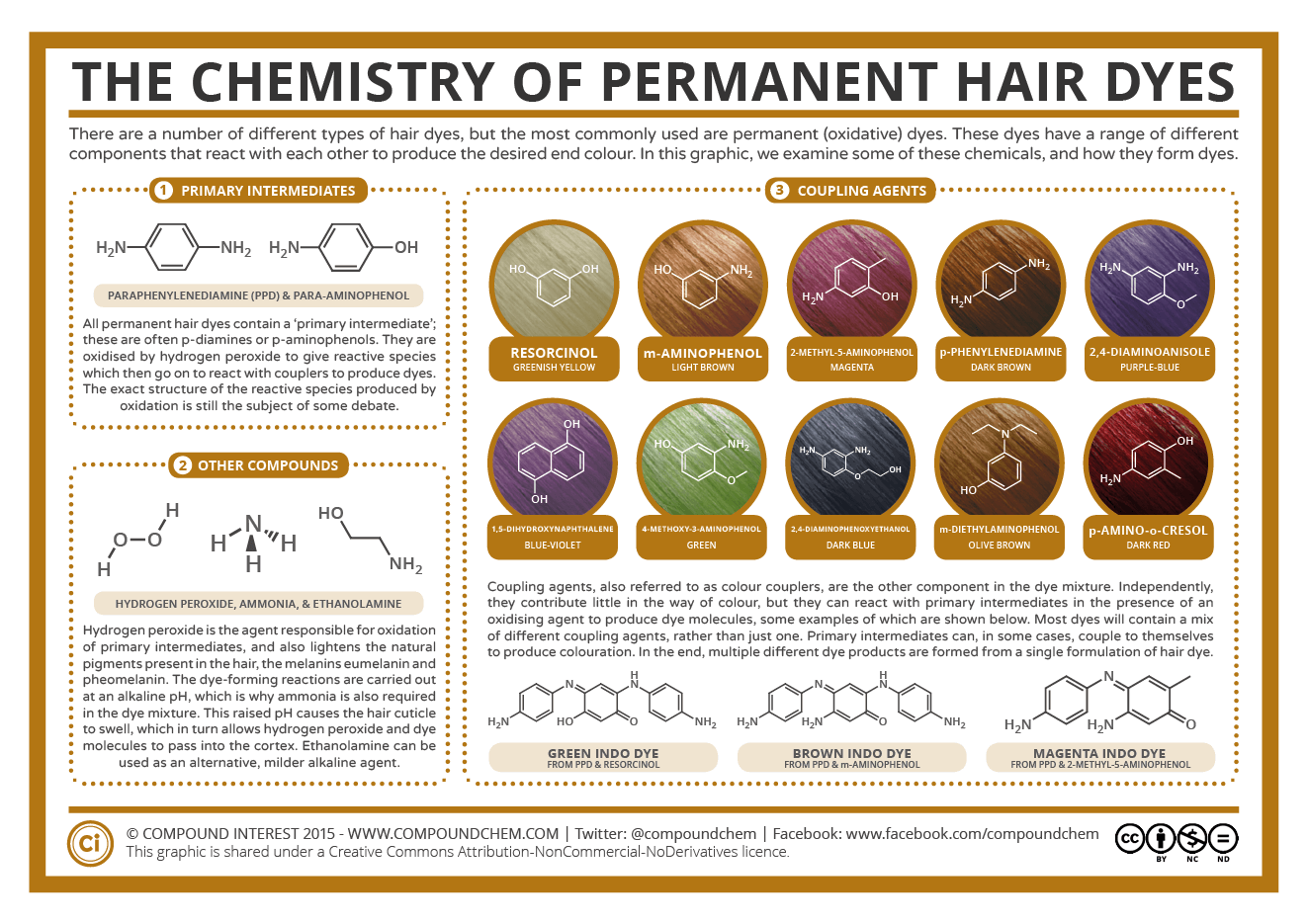

Your hair shaft is covered in cuticle scales, like the scales on a fish or like the shingles on a roof. The coloring molecules in hair dye are usually big — too big to get through the cuticle scales. So chemists came up with the idea of breaking these molecules into tiny subnanometer fragments, or precursors. When you apply dye to your hair, you’re diffusing these precursors through the hair shaft.

“It’s kind of like how you marinate a fish,” Huang said.

To facilitate this diffusion process, you need another chemical, an alkalinizing agent — often ammonia or an organic amine.

“What they do is open up the hair cuticle scales so that these molecules can get inside more quickly,” Huang said.

Once the small molecules get into the hair, an oxidizing agent, typically hydrogen peroxide, triggers a reaction that chemically combines the precursors. They come together to form color.

Melissa Piliang, a dermatologist with the Cleveland Clinic, said there are two main ways these chemicals then could get into our bodies.

“One is you could absorb it in the air during the dyeing process. Some of it becomes aerosolized and you could inhale it into your lungs,” Piliang said.

The other way is through the skin. Remember, to penetrate the hair cuticle, these molecules have to be teeny, and a smaller molecule is more likely to be able to penetrate the skin.

The chemicals could also potentially soak down through the hair follicles, which are highly vascularized, Piliang said.

So through our skin or hair follicles, compounds in hair dye could get into our bloodstream. That’s potentially worrisome, because a lot of the chemicals in hair dye are known or suspected to be linked to health issues.

One common precursor is paraphenylenediamine, or PPD, which is derived from petroleum. Because it gives a long-lasting color that has a natural look, it’s used in a lot of hair dyes. It often triggers allergic reactions, and it’s associated with blood toxicity and birth defects.

Ammonia is a respiratory irritant. And hydrogen peroxide is a skin and lung irritant (also the reason why colored hair can feel brittle and straw-like).

Those are just a few of the thousands of ingredients that can be found in hair dyes. Some other unsettling ones include lead (a neurotoxin), formaldehyde (a known carcinogen, and linked with miscarriages), and benzene (associated with leukemia).

Many other ingredients have yet to be studied, either in isolation or combination with one another.

All these health risks, known and unknown, don’t really line up with how we use hair dye — that is, in a very routine way. There are boxes in seemingly every grocery and drugstore. Professional coloring is the bread and butter of the salon business, more so than haircuts, perms, blowouts or anything else. In the U.S., more than 75% of women use hair dye at some point in their lives.

The cost of beauty

For a long time, Ronnie Citron-Fink was one of those women. She started coloring her hair in her early 30s to cover her grays. Her hair was always an important part of who she was. When she was young, it was long, straight, shiny and dark — think Cher — and it swung over her shoulders.

“I always got a lot of attention because of it,” Citron-Fink, who works as a journalist and editor for the Environmental Defense Fund, said. “It was my best beauty asset.”

For more than 20 years, Citron-Fink dyed her hair pretty much every other week. She’d go to the salon once a month, and in between those sessions she touched up her hair with dye she bought from Whole Foods. It was incredibly expensive, and incredibly time- and labor-consuming.

“I needed to cover this skunk stripe,” Citron-Fink said. “You know, the part would grow out the minute I walked out the salon door. I would get home, and I could part my hair and I could see the white. And that really bothered me.”

People have taken drastic actions to dye their hair for thousands of years. Ancient Egyptians made pastes out of lead oxide and slaked lime to rub on their heads. The Greeks mixed wood ashes and lye soap to darken gray hair, a caustic process that could burn one’s skin and cause one’s hair to fall out. In the Roman Empire, people pickled and fermented leeches, then slathered them onto their hair and sat in the sun for hours to achieve black locks.

We go to such lengths because different hair colors make us feel younger, more beautiful, more interesting. Hair is a central to societal beauty standards, and we learn to judge and make assumptions about one another based on hair.

“There’s a multi-billion-dollar hair and beauty business that perpetuates this myth that gray hair makes you look old and like you don’t care about your beauty,” Citron-Fink said. “ We get overt and subliminal messages from media to cover up. These are deeply-ingrained ideals.”

Flimsy regulations

About four years ago, Citron-Fink started to question her intensive dyeing regimen. She was sitting in a meeting about toxics reform in Washington. An environmental scientist was talking about the buildup of chemicals in our bodies, known as our chemical body burden.

“I could really almost feel my scalp tingle,” Citron-Fink said. “And I just kept thinking: What am I doing, putting all these chemicals onto my scalp?”

Being a journalist, she decided to do her research, which eventually turned into a book, “True Roots: What Quitting Hair Dye Taught Me about Health and Beauty.” In it, she breaks down how the Food and Drug Administration has shockingly little oversight over the safety of personal-care and beauty products.

“It does not pre-approve products before they land on the shelves,” Citron-Fink said.

A big reason for that is the law that gives the agency its authority, the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938. It’s a skimpy document, just a few pages long, that’s more than 80 years old. And under the act, the FDA doesn’t approve or test cosmetics.

Instead, that’s left to the Cosmetic ingredient Review, which is overseen by a trade organization that represents the chemical industry.

“In other words, it’s up to the responsibility of the product manufacturers to decide whether or not the ingredients of their products are safe,” Citron-Fink said. “It’s like we have the fox guarding the hen house.”

She adds that the FDA is small and under-resourced, so it’s not necessarily looking to change things. And even when the government does try to step in, it’s pretty much immediately challenged with lawsuits from a powerful chemical industry.

For instance, in 2018, the FDA banned the use of lead acetate in hair dye — scientists believe there is no safe level of lead in the body, and its use is regulated in other products, such as gasoline and paint. But Combe Inc., the parent company of Grecian Formula and Just for Men, challenged the ruling. And while the FDA is hearing the company’s arguments, a process that could take eight years or more, hair dyes containing lead acetate remain on the shelves.

All told, the European Union has banned more than 1,300 ingredients from use in cosmetics. The U.S. has banned 11.

Subscribe to The Pulse

What does science have to say?

If the FDA isn’t reliably testing the safety of beauty products, what about independent research? What does that mean for consumers?

The short answer is … it’s unclear. The scientific literature is largely inconclusive, with mixed and contradictory findings. Some studies have found hair dyes increase the risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, leukemia and bladder cancer, while other research suggests there’s no link between hair dyes and those cancers.

Melissa Piliang, the dermatologist, said such studies are exceptionally hard to do.

“We’re looking at thousands of people, and we live such varied lives and have so many different exposures, it’s really hard to determine which one might be causing which thing,” Piliang said. “We’re looking at using these chemicals for years and years, in which case it’s even harder to track what people are doing.”

Salon workers are one population to look to understand more. They’re the people with the highest exposures, so they might be a sort of canary in the coal mine.

A 2014 report called “Beauty and Its Beast” took a sweeping look at research that had been done on toxic chemicals and salon workers.

“We looked from skin issues to breathing problems, cancer concerns, effects on pregnancy and reproduction, various neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s disease,” said Alexandra Scranton, who authored the report and is the director of science and research for Women’s Voices for the Earth, an environmental-health nonprofit.

Common issues for hair dyes specifically included skin problems. A number of chemicals in hair dyes are known to be skin sensitizers and can cause dermatitis or rashes.

Respiratory problems are also common among salon workers. “And sometimes, it turns into a longer-term condition. Chronic asthma is a real problem,” Scranton said. “And the salon workers who are doing more of the hair bleaching and dyeing in the workplace are more likely to have these symptoms.”

Then there’s cancer. Hairdressers experience disproportionate rates of certain cancers, including lung, laryngeal and bladder cancers and multiple myeloma.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer, which is part of the World Health Organization, did its own analysis. “And their conclusion was that the occupational exposure to hair dye as a hairdresser, as a barber, was probably carcinogenic. Overall, that exposure was cancer-causing,” Scranton said.

What’s the takeaway?

How to make sense of this depends on who you consult.

Piliang, the dermatologist, said if you’re dyeing your hair maybe once every six to eight weeks and you follow the instructions — wear gloves, don’t leave the dye on longer than you’re supposed to, rinse thoroughly when you’re done — your risk is probably low.

“Tons of people use hair dye,” she said. “If there was a clear association, a clear risk from hair dye and cancer, I think even as challenging as these studies are, I think we could have found it.”

Others are more cautious.

“The way we regulate chemicals is that we make an assumption that there are safe levels or thresholds — but there aren’t, for many of the most well-studied toxic chemicals,” said Bruce Lanphear, a public health expert at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, British Columbia.

“What we’ve found over the past 10 or 20 years is that even levels that were previously thought to be safe or innocuous we now know are associated with death, disease and disability,” Lanphear added.

He said a precautionary and preventative approach to disease makes more sense than our current approach, which is focused on curing sickness after the fact. Part of making that happen is a tighter regulatory landscape, Lanphear said.

“We’ve continued to assume, despite all this evidence from other toxic chemicals, that a chemical is innocent, a chemical is safe until proven guilty,” he said. “The problem is, we are all guinea pigs in this experiment, and nobody’s asked us to sign a consent form.”

For all the uncertainty in the data on hair dyes, there are certain risk factors that seem to rise to the top.

A large systematic review done by an independent risk assessment firm found that people who have used hair dye since before 1980 are at increased risk for leukemia, possibly because some known carcinogens were banned and hair dyes were reformulated in the early ’80s.

A lot of epidemiological evidence suggests that pregnancy and early childhood are particularly vulnerable times for exposure.

And dark hair dyes tend to be worse, because they use more intense chemicals — so dyeing your hair a light auburn is potentially less toxic than dyeing your hair black. That contributes to another risk factor: Hair dyes and other beauty products put women of color at disproportionate risk for health impacts. Research has found that dark hair dyes could be linked to breast cancer in black women.

Ami Zota studies beauty practices and environmental justice at George Washington University. She said that, overall, black women have the highest levels of beauty product chemicals in their bodies — and they also show the highest rates of dissatisfaction with their hair, compared to other racial groups.

On top of that, “it’s women of color who are more likely to work in the hair salon,” Zota said. “And they may also live in neighborhoods that have more pollution, whether it’s from being near highways or dirty industries. We call this cumulative impacts.”

Ultimately, a lot of factors are at play. Alexandra Scranton, the author of “Beauty and Its Beast,” said people need to know this information, and make a judgment for themselves.

“Everybody’s different, everybody has different reactions,” she said. “You really have to look at what your health condition is, what kind of risks you want to take, and where you’re comfortable with uncertainty.”

Scranton says if you are concerned, there are a few things you can do. Familiarize yourself with the worst ingredients in hair dyes, and get used to reading the labels on products. Organizations like the Environmental Working Group or MadeSafe maintain databases that rate ingredients or products. Think about avoiding hair dyes during sensitive times, like pregnancy.

Researchers are also developing better hair dyes. Jiaxing Huang, the materials scientist from Northwestern University, has prototyped a graphene-based dye that coats the hair in large sheets, rather than using tiny molecules that can cross the skin barrier.

Tova Williams, a chemist at North Carolina State University, has developed a public database containing information about the structure and properties of more than 300 substances used in hair dyes. She hopes other researchers will use the database to predict health risks, and design dyes with safer ingredients.

There are certainly alternatives to ingredients like PPD, Williams said. “It’s not that we necessarily have to go this route. It’s just, it was discovered this route was effective, it was fast, it was cheap,” she said.

The chemistry of PPD is “nasty,” she added, but “it’s about profit.”

Michele Ortiz, the colorist who was experiencing all those health issues, eventually reached a breaking point. In 2006, she quit conventional hair coloring, went through a detox, and learned how to use plant-based dyes — senna for yellows, henna for reds, and indigo for darker colors.

Her health problems have gone away. “It’s like night and day,” she said. “I have a second chance to live my life.”

Ronnie Citron-Fink, the author of “True Roots,” found that even the dyes from Whole Foods that were branded to look natural still contained a cocktail of mysterious chemicals.

In the end, she decided to embrace her natural gray, though it wasn’t easy.

“I started out in this very angsty, I had age issues and I had beauty issues that I had to face,” she said.

But as her hair transformed from black to natural gray, Citron-Fink said, “I felt empowered, and I felt much more comfortable in my own skin.”

“You know, I kind of feel more ageless as opposed to anti-aging,” she said. “Like I’m not fighting anymore.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.