Delaware family with mixed-citizenship status divided days before baby is born

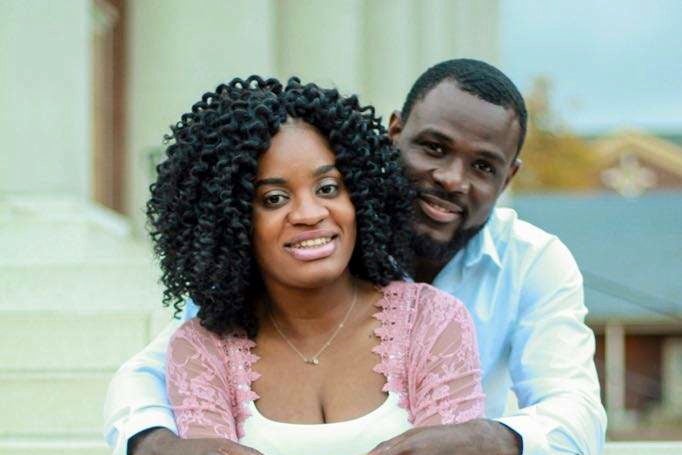

Sauveur Jean Jean, an immigrant from Haiti with a removal order, and his wife Vladine Thomas, a U.S. citizen, face an uncertain future.

Listen 4:41

Sauveur Jean Jean, an immigrant from Haiti with a removal order, and his wife Vladine Thomas, a U.S. citizen, face an uncertain future. (Photo provided by Vladine Thomas)

Vladine Thomas was eight and a half months pregnant when she went with her husband, Sauveur Jean Jean, for what she thought was a routine check in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Philadelphia.

A few minutes later, “the officer comes out and says he’s not going to go back with me,” she said. “I couldn’t drive because I was pregnant. I said, ‘How am I going to be able to go home?’”

Jean was taken to an immigration detention center in York County, Pennsylvania, and presented with a letter stating ICE’s intention to deport him “in the reasonably foreseeable future.”

From there, the questions mounted. Could he stay? If he is deported to Haiti, will she have to support him? Thomas is 26 years old and a U.S. citizen; Jean, 36, was apprehended trying to enter the U.S. by boat off the coast of Puerto Rico in 2013. Married in February, Thomas filed the form necessary for Jean to begin working toward his green card, called an I-130, in March.

“I always heard that if you file [a petition], everything is going to be OK … I always thought that,” said the Delaware resident.

Marriage is one of the only ways for someone who came to the U.S. illegally to become a legal permanent resident. Under the Obama administration, immigrants in the country illegally who were working toward legal status through a U.S. citizen spouse were sometimes shielded from arrest. That has changed under President Donald Trump.

In Jean’s case, a combination of factors may have contributed to his arrest on Nov. 17 after four years in the U.S.

New administration, longstanding question

In 2010, an enormous earthquake struck Haiti near Port-au-Prince, killing more than 200,000 people. A subsequent cholera outbreak claimed 9,000 more lives. Following these disasters, the U.S. largely stopped deporting Haitians without criminal records — including Jean — for several years. Immigration authorities let Jean into the U.S. with an “order of supervision,” requiring him to periodically check in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Immigration documents show he attempted to enter the U.S. on Oct. 13, 2013, near Mayaguez, Puerto Rico, “with the intent to reside and seek employment in Miami, Florida.” Instead, he settled in Delaware and found work in the chicken-processing plants. In immigration documents, his employment is listed as a “packer” for Perdue Farms.

In January, Trump issued executive orders immigration, wiping out old enforcement priorities to be the focus of deportation efforts. Anyone with a removal order, including Jean, became a priority.

“There’s no mercy in the system,” said Jean’s immigration attorney, Mary Chicorelli. “You just feel like it’s a never-ending fight, and you just don’t get anywhere, and the prosecutorial discretion isn’t being offered anymore.”

That discretion — basically a catch-all for describing times when U.S. immigration services may choose not to deport someone due to extenuating circumstances — was widely exercised during the Obama administration. It has largely ended by the Trump administration.

Chicorelli said discretion was a way of recognizing someone’s likely legal return to the country, thus saving the expense and hardship of deporting the person.

“Once the I-130 is approved, he can come back with a waiver. So why send them back when he’s going to come back [to the U.S.] anyways?” she said.

Chicorelli has asked for discretion regardless, as she tries to figure out whether Jean has any further opportunities to stay. On Thursday, Jean will appear before an immigration judge, who will assess his case.

William Stock, a Philadelphia immigration attorney and past president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, sees situations like Jean’s as endemic to U.S. immigration law, rather than a symptom of presidential turnover.

“This is ultimately a question that has always been problematic for the immigration system,” he said.

“We see it when someone doesn’t show up for their [immigration court] hearings, and, years later, they get picked up and they have a wife and kids,” he said, giving another example of when someone may have both a removal order and ties to U.S. citizens.

From the enforcement side, he said, “I think there is an attitude … that our orders need to have consequences because, otherwise, no one will take immigration very seriously.”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection spokesman Stephen Sapp declined to answer specific questions about Jean’s case, citing privacy laws, but he said attempting to “enter without inspection [at a location other than an official port of entry] is a serious violation of U.S. immigration law, may be criminally prosecuted, and generally results in an expedited removal order.” Those orders come with a five-year ban on returning to the U.S.

Waiting and hoping

On Dec. 5, Thomas gave birth to a daughter, Sephorah. Jamal, her 3-year-old son from a previous relationship, has taken to his new role as a big brother.

“He always says, ‘Can I kiss her?’ ” said Thomas.

Jean, in immigration detention at York County Prison, was unable to attend the birth of his daughter. Thomas said while they are both sad about the separation, she has switched into planning mode and is saving up money in case her husband is deported to Haiti. In that case, he will be eligible to apply for a waiver to return, based on their relationship, but the process can take several months.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen,” Thomas said. “I’m just here. If I have $100, I save it or send it to someone [so] when he gets there, he can buy something.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.