Beep, beep, beep – hospital alarms sound mostly without real cause

ListenAre computerized hospital alarms trying to tell us too much?

The beeping of monitors has become the ever-present audio wallpaper of hospital units.

Medical devices monitoring patients send off alerts when something is not quite right. Heart rate is off? Beep. Pulse low? Beep beep. Ventilator seems to be malfunctioning? Another alarm. IV medication bag almost empty – more beeps. Nurses hear them their sleep. For patients, they can be terrifying.

But the thing is, the vast majority of these alarms are unnecessary.

So much noise for no good reason

“Ninety-nine percent of the alarms that we saw were not actionable, meaning that a true alarm, an alarm that you needed to run in the door and save a patient, that was like a needle in a haystack,” said Chris Bonafide, a pediatrician and researcher at the The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The 99-percent figure applies to regular hospital units, but even in an intensive care setting, the vast majority of alarms do not mean a patient is in danger.

For example, the patient is a baby kicking his legs. It’s what babies do. So much so, in fact, the little sticker that holds the monitor’s sensor in place comes off. “So the device on the wall thinks that his heart rate is going way out of whack, but actually it’s just fine, it’s a happy kicking baby with a loose lead,” said Bonafide.

He has been studying what happens when you get false alarm after false alarm—a phenomenon called “alarm fatigue.” He says when he walks around on the hospital unit, he hears the beeping, but it fades into the background.

Specifically, he has been tracking how nurses respond to an alarm when they have already received lots and lots of alarms during their shift, and Bonafide found a relationship between that number and response times.

“As you got up to the most extreme group, nurses who had seen 80 or more alarms in the preceding two hours, the response was several-fold slower to future alarms, when they had been exposed to that many alarms,” he explained.

This is not a new issue. Healthcare providers started talking about it in the 1980s when hospitals and patient monitoring became much more high-tech. At the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Bonafide says over 1,800 different devices are used in patient care, and most of them can send off alarms. And every time an alarm goes off, a nurse on the floor is alerted and has to make a decision.

“Do I stop and interrupt this task that is probably really important, to go and check on that other patient?” he said. “It’s a difficult decision, and for a nurse it can happen hundreds of times in a single shift.”

Nurse, interrupted

“You may be calculating your medication dose, and drawing up your meds, and your alarm beeps, so you may turn to look at your patient,” said CHOP intensive care unit nurse Cara Tarity. “Then you have to start that process all over again, and not start in the middle.”

Tarity says having to start over all of the time can be very frustrating, but it’s something all of the nurses have become accustomed to in the ICU. She says her beeper goes off “too many times to count” in any given hour, letting her know that one of her patients’ monitors just fired an alarm.

Interruptions have been shown to cause medical errors, and among the medical staff, nurses suffer the brunt of all that beeping, because they’re the first in line to check and see why the alarm is sounding.

That may be part of the reason it’s taken so long for the medical community to pay attention to this issue, says Chris Bonafide. “The attitude for a long time was probably, ‘this is a nurses’ problem and not a doctors’ problem,’ so it didn’t rise to the level it has gotten to now. And the way we have reframed it is that it’s a patients’ problem.”

Watching patients deal with alarms

For his research, Bonafide captured hours and hours of video in patient care rooms, to find out when and why alarms go off and how quickly nurses get there. Medical student Mimi Zander reviewed this footage for the study, as part of her Society of Hospital Medicine’s student hospitalist scholarship.

She could see clearly how much the alarms were impacting the wellbeing of patients.

“As an alarm fires, I can see if that woke the child up, or if it woke the parent up, and if the parent is unsettled by the amount of alarms,” she said.

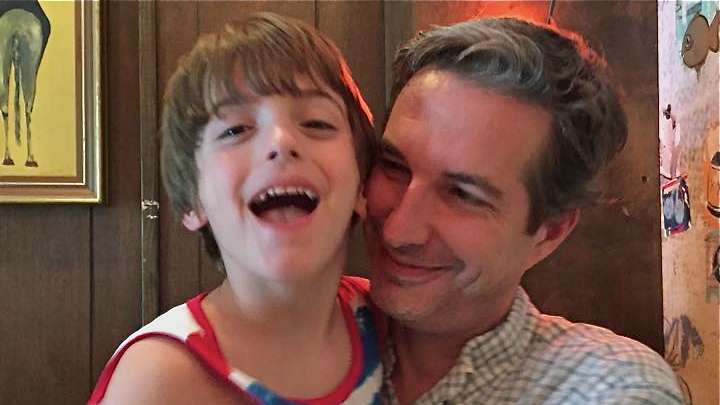

“Any one of these alarms sounds to you like a team of doctors should be rushing in, to take care of the situation,” said Mike Kennedy of Philadelphia. His son Alex was born just 27 weeks into the pregnancy. A tiny premie weighing just two pounds, he spent three months in the CHOP NICU. The isolette Alex was in was in the corner of the NICU, so it would take nurses a little longer to get over when alarms were beeping.

When everybody thinks it’s nothing, but this time it’s not

Kennedy remembers the constant alarms and the nurses reassuring him and his wife Kristine that it was nothing. “But there was one time in particular that it wasn’t nothing,” recalled Kennedy.

The PulseOx alarm went off, and when Kennedy and his wife looked up to the monitor, they realized that Alex’s oxygen level was going down rapidly. It fell below 30 percent.

“We could see formula coming out of his nose and mouth, and he was choking,” Kennedy remembers. “We called the nurses and they were like, ‘It’s okay it’s okay,’ and we said, ‘It’s not okay, we need you to come here.'”

The incident haunted Kennedy—the sound of the PulseOx alarm filled him with dread during the family’s remaining weeks in the NICU. He says the sound of hospital alarms makes him anxious and upset to this day, even though Alex is a healthy six year old now, and going to Kindergarten.

What could medicine learn from aviation?

Alarm fatigue has become a top priority for hospitals, and researchers everywhere are looking for ways to reduce the noise.

Among them is engineer Keith Karn, who used to work in aviation, but he’s now human factors specialist doing product design for a company called BresslerGroup. He’s attacking this problem with a seemingly basic question: Why can’t an ICU be more like a cockpit?

He says pilots would never put up with all of the beeping. “In an aircraft cockpit, you wouldn’t tolerate it at all to have false alarms, you’d ground the airplane and take it in for maintenance and say, ‘What’s the matter with this thing?'” he said.

Karn says one important lesson medicine could learn from aviation is to streamline informatio, and to offer it at the right time. “For example, in the case of combat, in the heat of the battle, the pilot doesn’t need to be reminded that his landing gear is retracted, but when he comes back he wants to know and check that his landing gear is down.”

Karn is working on a small pilot study with several Canadian hospitals.

Finding fixes and tweaks

CHOP Pediatrician Chris Bonafide says one simple step to reduce false alarms is to put only patients on monitors who truly need to be monitored—those who are critically ill.

And, he says monitors need to become smarter and only go off if certain conditions persists.

“We have the capability in some devices, to say, ‘Don’t fire an alarm until that condition has existed for more than X number of seconds.'”

Bonafide says other steps are to switch out the sticky sensors that hold monitors in place every 24 hours, and to track which patients on a unit are setting off the most alarms and investigate why this is happening.

He is now doing a five year study that includes more video observations. He says he hopes that within the next ten years or so, alarms will finally become the useful tool they were intended to be, alerting care providers only to true problems.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.