Awaiting ruling on ACA, states ready back-up plans

Listen

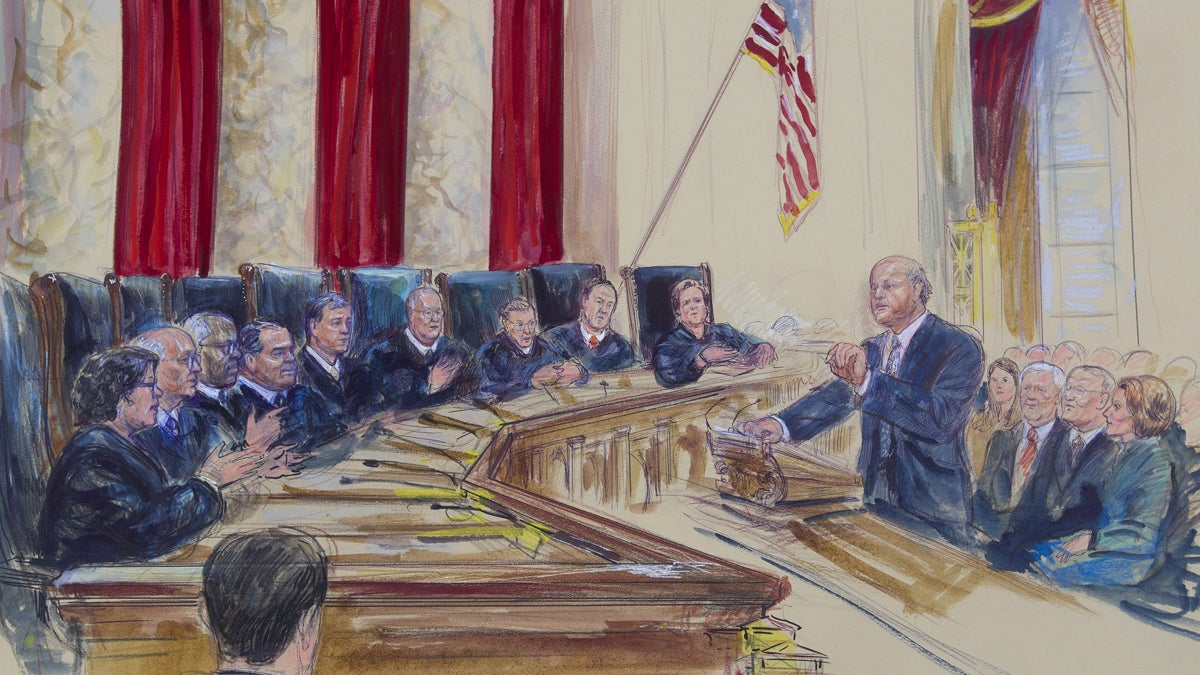

This courtroom artist rendering shows Michael Carvin

The U.S. Supreme Court slated to rule this month on a case that could jeopardize the health coverage of tens of thousands of people, so are state leaders ready?

Delaware and Pennsylvania are taking some unusual steps in preparation for the decision: submitting a contingency plan.

At issue is whether millions of consumers in some 34 states with federally run marketplaces—including Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey—are eligible for financial assistance to purchase coverage under the Affordable Care Act. The lawsuit, King vs. Burwell, argues that discounts apply only to states that run their own marketplaces.

That’s why Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf said he submitted blueprints to the federal government Monday, as part of a June 1 deadline, to set up a “state-supported” marketplace.

“My biggest concern is, do we have a fall back if we need it?” said Wolf, who last month sent a letter of intent to the federal government to create a state-based marketplace.

Wolf stressed the plan submitted this week is non-binding and hinges on what the court rules.

The state’s new insurance commissioner, Teresa Miller, said the process was a bit rushed.

“It’s forcing us to put together a plan that frankly most states spent years developing, and essentially we’re having to do that in months,” she said.

It’s unclear how soon the state could transition to a model where it would oversee the funding and regulations.

“I’m just doing this because I want to be prepared,” said Wolf.

Anticipating a “death spiral”

A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis estimates that upwards of 700,000 Pennsylvanians could be eligible for subsidized coverage next year. As it stands, nearly 400,000 Pennsylvanians have qualified for discounts, including 27-year-old Kathryn Ryan, a restaurant server in Philadelphia.

“I was excited because, if it weren’t for Obamacare, I wouldn’t be insured at all,” said Ryan, who aged out of her parents’ insurance plan the year before. “I wouldn’t have the ability to go to the doctor, which is pretty crazy.”

Ryan, who’s studying social work, can afford the coverage thanks to a $200 monthly discount that brings her premium down to $60. She hopes to keep her insurance until she’s able to find work with benefits, but like many, she wasn’t aware of the upcoming Supreme Court case and that her subsidies might be at risk.

Policy analysts are concerned that without subsidies, Ryan and others could no longer afford coverage and drop it. Hospitals and health providers would lose payments and “the whole individual market in states could collapse,” said Trish Riley, executive director of the National Academy for State Health Policy, or NASHP.

Sick people who need expensive care would keep their coverage, but then “premiums go through the roof,” Riley explains, at which point no one can afford it.

She and others often refer to this as a “death spiral.”

Pennsylvania bucking the trend

While Pennsylvania may have come out with a contingency plan, that is not the norm.

“Pennsylvania stands out,” said Joel Ario, a health consultant with Manatt Health Solutions. Ario served as a Pennsylvania insurance director under the Rendell administration and then became a marketplace director with the federal government.

He said many states officials are exploring options behind the scenes, but supporting an actual plan at this point “is a political nonstarter” for at least a third of states with federal marketplaces.

That’s because it means “standing up and saying, ‘I want to work with this law in a public way in a state-based exchange.'”

Wolf, a democrat, recently took over for a Republican governor in Pennsylvania. But elsewhere, a lot of state leaders don’t want anything to do with the law, and by default, have federal marketplaces.

Arizona has enacted legislation prohibiting a state-based marketplace, with similar bills pending in several other states.

Conversely, 11 states have at least proposed legislation to create a state-based exchange, according to Riley with NASHP.

“It’s kind of the equivalent of a weather forecast that says, ‘it’s going to pour today, so you bring your umbrella in case it does.’ And I think that’s where states find themselves,” she said.

In neighboring New Jersey, a Department of Insurance spokesman said it’s too soon to talk about alternative plans.

“It is premature for us to publicly discuss contingency plans when no one knows how the U.S. Supreme Court will rule, when it’s ruling may take effect, or what, if any, options the court, Congress or the White House may offer the states,” stated Ed Rogan in an email.

In neighboring Delaware

Officials in Delaware, which has been more involved as a hybrid “partnership” marketplace that still falls under a federal marketplace category, have been exploring all options.

“We haven’t shut any door, and we haven’t made a definitive answer just yet,” said Rita Landgraf, Delaware’s health and social services director.

Landgraf said Delaware officials considered a regional marketplace with other states, but it was too complicated and hasn’t gained traction. The federal marketplace initially won out over a state design due to the size of the state and the cost of running its own platform.

Now, as a contingency like Pennsylvania, the state has submitted a plan for a state supported marketplace.

“Eighty-four percent of those who purchased plans on the marketplace received a financial subsidy, so that is critically important to our constituency that those subsidies are available to them,” said Landgraf.

Some blueprint details

With the federal marketplace system and healthcare.gov finally running smoothly during year two of open enrollment, Landgraf said one consideration moving forward is whether any big change would impact a process that’s finally working.

Both the Delaware and Pennsylvania marketplace proposals would still use that federal IT system and the healthcare.gov website, though each state would oversee marketplace funding, consumer assistance and insurance plan regulations.

It’s unclear what the federal government would require of any state-based proposal as it awaits the Supreme Court decision, but overall, the agency appears willing to work with states.

“They [HHS officials] haven’t given any formal guidance,” said Miller, the insurance commissioner for Pennsylvania. “We know that this type of model is possible because it’s in existence today, but it’s not defined anywhere … which has made our planning that much more challenging.”

Similar state-based models exist in Oregon, New Mexico and Nevada “by default,” said Miller. They came about when those states, opting to be state marketplaces, were not ready in time with their own systems.

Miller said a state-supported marketplace in Pennsylvania would likely be funded in the same way as the federal marketplace: through an assessment fee on premiums. Today that fee, managed at the federal level, is 3.5 percent.

“If we moved into a supported state-based model, we would collect the assessment and then we would probably need to reimburse the federal government for use of their platform,” said Miller. “That’s one of the big unknowns in this model right now, how much the federal government is going to charge for use of healthcare.gov.”

Riley, with NASHP, says moving forward, it would be hard for any state to set up a “full-fledged” state-based marketplace, developing its own IT platform and eligibility structure for subsidies.

“That’s a very big lift, and the states that set those up [already] got significant federal help to do so,” she says, adding that such funding is no longer available. “It takes a long time.”

As for how soon Pennsylvania, Delaware and others states could actually make the switch, if need be, to a state-supported marketplace?

“It depends on what the federal government can and is willing to do. And how one defines ‘established.’ Does that mean by the state or for the state? What would a state have to do to accomplish this?” said Riley.

As for Kathryn Ryan, a waitress in Philadelphia with coverage through the marketplace, the thought of these possible disruptions with her coverage “is all nerve-wracking,” as she finally is starting to figure out how her insurance plan even works.

“I hope it just stays the way it is,” she said.

Federal officials aren’t saying how many other states have contingency plans, but that’s in part because right now, all eyes are focused on the biggest unknown of all—the Supreme Court.

A decision is expected by the end of this month.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.