Why we can’t stop using our phones while driving

Notifications and texts offer immediate gratification some can’t resist when behind the wheel. To kick the habit, some behavior rewiring is needed.

Listen 08:44

Common sense says that phone use while driving is a bad idea. Yet nine out of 10 drivers admit to doing it. (Image courtesy of Oregon Department of Transportation)

May 26, 2018, started like any other day for Jacque Tierce in Larned, Kansas. A little before 8 a.m., she let the dog out. Then, she heard sirens.

“I began to pray for whoever was involved,” Tierce said, “because we live in a small town, and it’s not often that you really hear sirens.”

Those sirens turned out to be for Tierce’s daughter, Danielle Delgado, a 22-year-old single mom. Delgado had been in a car crash. She died that same day.

Two days later, the Kansas Highway Patrol visited Tierce’s home. They explained to her that Delgado had been on Snapchat and texting at the time of the accident. She was driving 65 to 70 mph and rear-ended a semi-truck.

“She didn’t brake. She never even saw it,” Tierce said. “It was just a huge blow. It’s not something that I really expected to hear.”

After her daughter’s death, Tierce started a campaign called #DoitforDanielle.

She does a lot of public speaking and presentations in schools, where she shares facts like this: It takes approximately 4.6 seconds to read or send a text message. At 70 mph, that’s like driving the distance of 1 ½ football fields with your eyes closed.

We’ve heard these statistics and odds before. One in every four car accidents involves cellphones. Billboards shout at us, “It can wait.” Common sense tells us that using our phones while driving isn’t worth a life. Yet nine out of 10 drivers admit they use their phones while driving.

Time to confess

I’m not proud of it, but I use my phone pretty often while driving. I toggle between podcasts, music and audiobooks. I surf social media, make phone calls, and even write emails. I know it’s a dangerous habit — so why do I still do it?

To find out, I talked to Kit Delgado, an emergency physician and professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He’s interested in what’s called behavioral economics — the factors that go into our flawed decision-making when we use our phones while driving.

For instance, there’s present bias, meaning we give more weight to benefits in the present moment. “People tend to respond to immediate gratification, rather than delaying things to prevent crashes in the future,” said Delgado (who was not related to Danielle Delgado).

Then there’s overconfidence bias. If you ask a room of 100 drivers how they compare to other drivers, 90 percent will say that they’re safer than other drivers.

And there’s recency bias. “You just completed hundreds of trips without getting into a crash. You probably used your phone for some of them,” Delgado said. “So when that phone ping goes off, you’re not even calculating that risk of getting into a crash, because you’ve never experienced it before.”

There are lots of efforts to get us to think straight when driving. High schools now run programming around phone use while driving. There are media campaigns to shift cultural attitudes. And 48 states ban texting and driving by law.

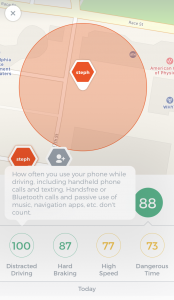

Kit Delgado is working on the technology side, with an app company called TrueMotion that tracks driving behaviors such as texting and other distractions. The idea is to pair good driving with incentives, like discounts on insurance or cash rewards.

I decided to try one of TrueMotion’s apps, driving and using my phone as I normally would. But after about two weeks using the “family” app, I got 100%, an A+, for my distracted-driving score. How is that possible?

I hopped on a call with Rafi Finegold, vice president of loyalty and behavior at TrueMotion. First, he explained to me how the apps work.

TrueMotion’s apps don’t see any of the content you’re looking at, or the specific apps you’re using. From your phone’s operating system, they can tell when you’re making a call, and whether your screen is unlocked.

But beyond that, everything the apps collect is from the phone’s sensors — things like accelerometers, gyroscopes and magnetometers — that are extremely sensitive and can sample data up to a hundred times a second. TrueMotion runs that data through a bunch of algorithms, which deduce your behavior.

Turns out, TrueMotion did register my phone use. But it didn’t count because TrueMotion considered it passive use. I was tapping and swiping the screen, but my phone was in a mount — not in my hand.

“That was kind of a UX [user-experience] decision that we made, because we didn’t want to ding people for behaviors that they considered to be safe,” Finegold said. “Having your phone in a mount is probably safer than interacting with your phone in the hand.”

Still, I drove about 13 hours and passively used my phone almost 30% of the time, Finegold told me. That percentage seemed high to me. If you asked me to give myself a grade, I’d probably give myself a C. I felt distracted.

Finegold said TrueMotion is planning to come out with a “mounted tap” detection feature this year, which should account for some of my concerns.

But, to be real, my concern goes beyond how well an app can track my driving behaviors. What truly concerns me is that my impulse to use my phone while driving was really strong, even though I was aware of the consequences. So this is a deeper problem.

Kicking the habit

“The worst offenders — the drivers that are distracted on their phone almost 30% of the time — we call these folks phone addicts,” said Jonathan Matus, the CEO of Zendrive, a company that studies driving behavior through data and analytics.

Last month, Zendrive published its yearly report, based on more than 160 billion miles of driver data. It found that one in every 12 drivers is a phone addict.

“This is our generation’s drunk driving. We are conditioned to have these devices next to us, six feet or less, throughout the day. And we become dependent on them, and it’s increasingly difficult to think of the time on the road as time that should not be experienced through the smartphone,” Matus said.

Like other addictions, smartphones are hacking into reward circuits in our brains, he added.

“The way notifications and a lot of the experiences on the phone work is they trigger some of the neurochemistry and neuromachinery that was created to help us survive in the wild,” Matus said. That includes neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin, which play a huge role in regulating pleasure and attention.

Maybe one of the best things you can do for reducing phone use while driving is to practice leaving your phone behind in daily life: “Put your phone in the fridge, go out for a stroll around the block,” Matus suggested. “Talk to some strangers. Cook a meal. Enjoy the weather.”

You can also rewire your circuits, by reframing what makes you feel good. Make it a goal to drive without using your phone, and reward yourself if you succeed.

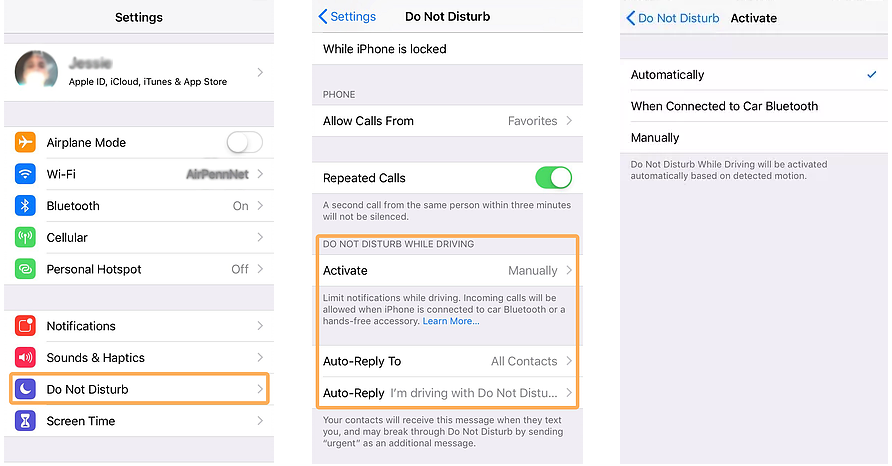

Here is one super-easy thing to help: iPhones have a setting called “Do Not Disturb While Driving.” Androids have a similar mode.

It takes 10 seconds to set up. You can turn it on so it’s automatic, or add it to your control center, where your airplane mode and flashlight shortcuts are. When you’re driving, you can still play your music and navigation — just load your maps and playlists at the start of your drive.

The setting prevents calls and messages from coming in, unless the sender says it’s an emergency, which removes the temptation to respond to that message from your boss, or your new crush. It’ll send an auto-reply to anyone who tries to contact you, so you don’t have to worry about leaving people hanging.

Kit Delgado, at the University of Pennsylvania, thinks if this setting comes as the default on new phones, or people just start using it across the board, it will simply become a new social norm.

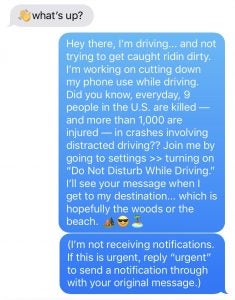

And people can customize their away messages, have fun with it. Here’s mine:

“Hey, I’m driving and not trying to get caught ridin’ dirty. I’m working on cutting down my phone use while driving. Did you know — every day, nine people in the U.S. are killed — and more than a thousand are injured — in crashes involving distracted driving? Join me by going to settings, and turning on ‘Do Not Disturb While Driving.’ I’ll see your message when I get to my destination … which is hopefully the woods or the beach.”

Editor’s note: In a previous version of this story, Jonathan Matus’ name was misspelled. It has been corrected.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.