At ALS clinic, supporting mental health care not an afterthought

Living with ALS is an extraordinary psychological challenge, and at this clinic, mental health services are integrated into patients’ medical care.

Listen 2:40

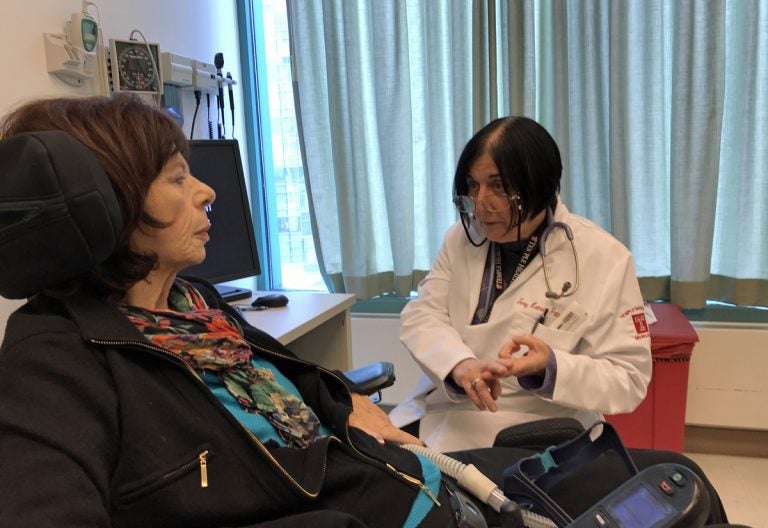

Dr. Terry Heiman-Patterson meets with Pat Vitkow, a patient with ALS. (Joel Wolfram for WHYY)

Pat Vitkow remembers something she saw from her first visit to the Philadelphia clinic where she gets treated for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. Another patient, a woman in a wheelchair, needed someone else to wipe her nose for her.

“I thought to myself, that’s not going to happen to me,” said Vitkow, who was diagnosed with ALS five years ago. “Now somebody wipes my nose, because I can’t reach my nose.”

Vitkow, 74, had her first symptoms seven years ago when she was still working as an administrator for a large medical group in Atlantic County, New Jersey. Now, she is in a motorized wheelchair, and uses a ventilator to help her breathe during a recent appointment with Dr. Terry Heiman-Patterson at the MDA/ALS Center of Hope at Temple University.

Getting diagnosed with ALS — which is also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease — can be devastating for patients and their families. The rare and fatal disease slowly robs patients of their ability to walk, speak, move, and breathe.

Heiman-Patterson, a neurologist and the clinic’s director, says the average life expectancy for a person with ALS is three years or less after getting diagnosed. There is no cure, but many patients hold out hope for a medical breakthrough that might save them.

“Every month, there’s another loss, and you’re facing loss for the entire time you have this disease,” she said.

Living with that prognosis is an extraordinary psychological challenge, and at this clinic, mental health services are integrated into patients’ medical care. Patients meet with nurse counselor Mary Holt-Paolone every time they come in. Holt-Paolone says that physical aids can only do so much if patients can’t find a way to cope emotionally.

“They’ll have their walker sitting beside them and they’ll get up and walk without it,” said Holt-Paolone. “Or they won’t want to even see the walker because it just reminds them of what’s happening to them.”

Holt-Paolone says symptoms of depression affect the majority of patients after their diagnosis, while about 20 percent suffer from chronic clinical depression.

She also works to support the mental health of family members and caregivers. Vitkow’s husband Barry Hornberger said he’s still grieving the loss of the other plans they had for their lives.

“This was like a stab in the gut, from day one,” Hornberger said.

Holt-Paolone says she helps empower patients to control what they can about their lives.

“We have two choices,” she said. “We can let ALS kill you before you actually leave this world. Or, we can do everything that we can in our human power to help you live every moment as best you can with it.”

Editor’s note: This story was edited to reflect that Vitkow had her first symptoms seven years ago, not five, which was when she was diagnosed. We regret the error.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.