After fleeing violence in Jamaica, gay man seeks refuge in America

Listen 11:06

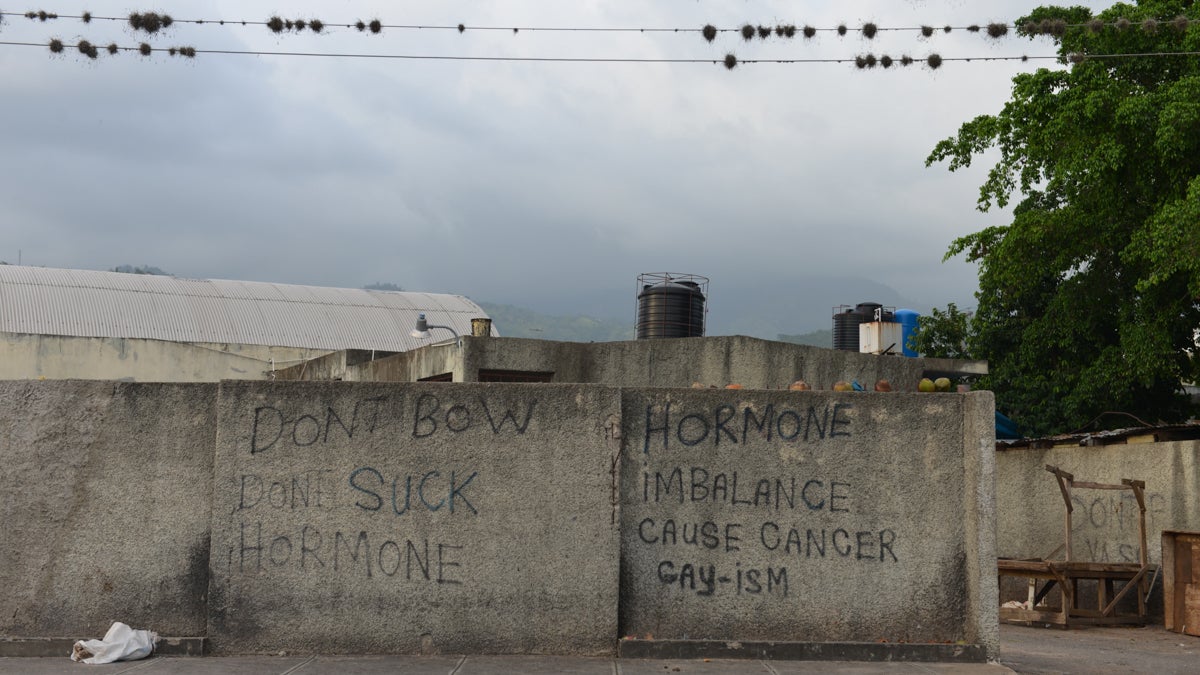

Street graffiti with an anti-gay message covers part of a privacy wall in a neighborhood in Jamaica. Advocates say much of the homophobia is fueled by a nearly 150-year-old anti-sodomy law that bans anal sex as well as by dancehall reggae performers who flaunt anti-gay themes. (AP Photo/David McFadden)

Anti-gay prejudice is written into Jamaican law. A colonial-era rule criminalizes male intercourse and LGBT activists say talk of jail time and prison is used to intimidate people.

I’m a new doctor—and when I met Malcolm, his story changed the way I do my job.

He’s worried this story could make his family in Jamaica unsafe, so “Malcolm” asked that we don’t use his real name.

In 2012, he was in Jamaica, heading home from work in a shared taxi with a bunch of strangers.

“Apparently, there was somebody in the taxi who wanted to rob the car or something,” he said.

The man pulled out a gun. He ordered everyone out of the car.

“Now when I got out of the car, all of his attention now started to focus on me. And he left everybody else, he had the gun on me because when I walked out he realized that I was gay. He immediately pointed the gun at me and was like ‘I didn’t know a fish was in here,'” Malcolm said.

Fish is a derogatory term used to harass and insult gay men.

Malcolm is in his mid 20s now. But let’s rewind even further to his childhood in a small town in Saint Ann Parish. Malcolm says everyone knew everyone in his town, and everyone knew he was gay.

“I talked very squeaky for example,” Malcolm said. “Some would say ‘you talk like a girl’… the way how I walk. I would look at other boys my age. I don’t look like that. It’s sort of wishing to be normal.”

Malcolm’s kind of “different” is tough in Jamaica, says Sarah Hamilton. She’s Jamaican, and a human rights lawyer for Amnesty International.

“Jamaica is a deeply religious and Christian country. I think 70 percent of Jamaicans identify as evangelical Christian,” she said. “There’s widespread belief that homosexuality is actually against the laws of god, and is seen as a threat to their religion. And as a threat to religion, it’s a threat to their identity.”

Malcolm says that as a boy, strangers in the street would hiss threatening words at him. In school, he was bullied. He told his teachers at first but eventually stopped complaining because no one helped. He felt afraid. He had nightmares. Even the dance hall music that was popular when Malcolm was a teenager was full of threats and slurs.

“It’s very normal to go to a dance or whatever, and people will have these aerosol cans and they will use a lighter and spray the fire out,” Malcolm said. “It’s a symbol that people who are gay need to be burned.”

Malcolm says he endured “name-calling, people saying ‘people like you must die, you don’t deserve to live,'” he said.

It wasn’t empty talk. One evening, Malcolm was walking home from classes and he was attacked by a group of men. “They did a number on me,” he said. “They beat me really bad, they dragged me to the alley calling me names, going on and on, they punched me, they kicked me on the ground. They beat me really bad.”

So he did what most of us would do.

“I went to the police station and I told them what happened, and the cop, he looked at me and was like, ‘That is what you deserve.’ That’s exactly what he said to me. And I went into a public restroom and I cleaned myself up and then I went home.”

At that moment, Malcolm realized the police wouldn’t protect him–no one was going to protect him.

“Even if somebody tries to stand up for you, then they go against that person, it’s like ‘Oh you’re trying to protect this gay man from us–are you gay too?'” Malcolm said.

An evolving history

Anti-gay prejudice is written into Jamaican law. A colonial-era rule criminalizes male intercourse and LGBT activists say talk of jail time and prison is used to intimidate people. And then in 2006, a Time magazine headline asked if Jamaica was the most homophobic place on earth—and that kicked off a slew of reporting on the island.

“The Pulse” requested an interview with Minister of Justice Delroy Chuck and Jamaica’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations Ambassador Courtenay Rattray—to get comment on accusations of homophobic violence and allegations that there’s a culture of intimidation on the island.

After multiple follow-up emails and phone calls, Kurt Davis, Rattray’s counselor for social, humanitarian and cultural affairs, referred the interview request to the embassay in Washington, D.C. Davis’ response was sent after the radio production deadline for “The Pulse.”

Rohan Powell, Delroy Chuck’s adviser, said the minister was not available for an interview.

Writer Suzanne Persard—whose parents are from Kingston–says as a ‘queer Jamaican-American woman,’ living in the United States, she keeps tabs on Jamaica.

Persard says homophobic violence on the island should be viewed in the context of island-wide “criminality and instability” linked to persistent poverty.

“How safe you are is very tied to socioeconomic status,” she said.

Poverty makes the human rights situation difficult for many people living there, she said.

Persard has visited the island several times to do LGBT activism work.

“The narrative that is perpetuated in the West sometimes feels radically different than the activism that’s happening on the ground,” she said.

The country’s track record is clear, but it’s also time to update Jamaica’s image, Persard said. “More people are coming out,” she said and when activists held the country’s first public Pride celebration in 2015, the then Minister of Justice Mark Golding urged Jamaicans to respect the event.

“A lot of LGBT activism on the ground has been happening and that’s definitely something that I think a lot of people are surprised to learn about,” Persard said.

So Jamaica’s story has evolved, but Malcolm—who was bullied as a boy—and taunted as a teen—says as he grew older, Jamaica got worse for him.

Fast forward a couple years, and Malcolm is where we met him at the top of this story–with a gun to his head and singled out for being gay.

“He put the gun in my face and I was trying to get away,” he said. “I’m not really entirely sure what happened after that. He gun butted me and then he shot me.”

Knocked unconscious and bleeding from his leg, Malcolm eventually came to lying on the side of the street. He spent several weeks recovering from the gunshot wound and a brain injury. Depressed, he felt he might take his own life, or eventually someone else would. So Malcolm left Jamaica.

With little money and no job, he arrived in New York City on a tourist visa, with no intention of returning home.

How I met ‘Malcolm’

I’m doing part of my ER residency in Elmhurst, Queens—a neighborhood of immigrants—and that’s where I met Malcolm.

Walking out of the subway, it seems like everyone is speaking a different language. A Spanish bodega butts up against a Korean grocery store, which is filled with Bengalis.

At first, Malcolm was reserved and nervous. It took awhile, but eventually, he opened up and told me just how scary it was for him growing up in Jamaica.

“It’s constant it’s every day, it’s been a nightmare for the entire 20 odd years, I don’t know what it is to live,” he said.

Emergency medicine physician Dinali Fernando, one of my supervising doctors, introduced me to Malcolm. Elmhurst Hospital, where Dr. Fernando and I work, cares for lots of people who are new to America.

“They’re undocumented, uninsured or underinsured, and so they end up utilizing the [emergency department] as their primary source of entry into the healthcare system–it’s their portal of entry,” she said.

Years ago, hospital leaders wanted to know more about the immigrants who come through the emergency room–so they surveyed 500 patients and asked two questions:

“Were you ever threatened or harmed by groups such as the government, police, military or rebel soldiers?” and “Some people in your situation have experienced torture–has this ever happened to you or your family?”

Nearly seven percent of the patients surveyed said ‘yes.’ They had experienced some form of torture. That may sound small, but the ER at Elmhurst Hospital has 90,000 patient visits every year. That means during one busy shift, I might see one or two people who’ve experienced torture.

The survey led to the creation of the Libertas Center for Human Rights. It’s an ER-based program, and Dinali Fernando is the medical director.

Eventually, Malcolm made his way to the Libertas offices, tucked away in a quiet, old part of the hospital. There, he learned he was more than a victim of a hate crime.

Remember when Malcolm spoke to his teachers? When he went to the police? Malcolm says they looked the other way—and in at least one instance, authorities condoned violence against him. Dr. Fernando says Malcolm’s experience makes him a torture survivor, according to The United Nations and United States’ definitions.

“If there are no systems in place to protect you, or the systems that are in place don’t offer protection, then you will qualify,” Fernando said.

The center links asylum seekers with medical care, counseling and a caseworker. The plan is to help Malcolm get well as he works to gain legal status in the U.S. It’s a long, winding process, that means talking with attorneys and sharing ugly details from the past. Dr. Fernando did a forensic evaluation of Malcolm—a medical and psychological exam—and later wrote an affidavit to support his asylum case.

“The case for asylum is that you cannot return to your home country, because if you go, your life will be in danger,” she said.

The Libertas Center is studying the people it serves and their interactions with the U.S. healthcare system. The researchers found that seven percent of surveyed patients never had a physician ask them about torture.

In medicine, they say you only find something if you’re looking for it, and doctors, like me, simply weren’t looking. We don’t ask the right questions.

Now, I’m on the lookout. But that’s easier said than done.

“Part of it is just to weave it into your conversations,” Fernando said.

“If they say they’re from a country where you know there’s a lot of political turmoil and harm, then that can be something to kind of initiate the conversation. Then when you’re doing the physical exam on the patient, if you see scars, you can ask them, what is this from.”

“Threats and psychological is the predominant type of torture, followed pretty closely by beatings,” she said. “And then wounding and maiming, and then rape and sexual violence.”

There are centers like Libertas at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, another in Minneapolis and about 30 other places across the country.

Malcolm’s asylum papers have been filed, but it can take three or four years before you get a hearing with a judge. Until then, he’s living in legal limbo, waiting his turn.

“This is my home,” Malcolm said. “I can’t picture myself living anywhere else right now.”

Alex Stern contributed to this story.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.