A secret mission to dump radioactive cargo in Atlantic Ocean tells history of nuclear tests

Answer to decades-long mystery uncovered in the archive at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia.

Listen 16:09

In a photo from the Papers of J. Hartley Bowen Jr. at the Science History Museum, workers load a barrel of contaminated waste into a B-17 aircraft. (The Papers of J. Hartley Bowen Jr. at the Science History Museum)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

In October 1947, George Earle IV, a Navy reserve pilot, reported to Mustin Airfield near the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

He watched as men from the military listened for clicks as they hovered something over 55-gallon canisters. Earle was not a scientist, but he assumed this instrument was a Geiger counter, and he knew Geiger counters measured radiation.

Eventually, they hovered the instrument over him.

Then, with looping straps, the men loaded the canisters one by one into the hull of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, a heavy bomber plane.

It was Earle’s job to fly this plane “low and slow,” so as to not disturb the canisters, late into the night 100 miles southeast of Atlantic City.

There, out over the dark ocean, the plane’s crew would open a hatch and tip the canisters into the sea.

Earle flew three secret missions that month.

Each time went the same way. The men never revealed to Earle what he was helping get rid of. It was all “very hush-hush,” Earle later said in a local news report.

The World War II pilot seemed like the perfect person to keep a secret. He was quiet and didn’t like to talk about his service.

“Every Sunday night, we’d watch ‘Victory at Sea,’” his son George Earle V said.

The son remembered quiet nights huddled around a black-and-white TV set watching documentaries about the war. Only then would his father’s emotions surface.

“We’d sit there for an hour, and Dad would just be in tears seeing his friends being killed,” said Earle. “He was the only original pilot alive at the end of the war out of his whole squadron.”

His father’s silence could be mistaken for cynicism, but he was not cynical. Not yet.

Earle came from a storied patriotic family whose earliest known ancestor survived a fall from the Mayflower. His forebearers went on to start businesses, befriend presidents, and accrue vast amounts of wealth.

Earle’s family owed everything to the American project; a debt his father tried to make good on.

In 1935, George Earle III was elected governor of Pennsylvania and implemented his “Little New Deal”: policies that supported civil rights laws, unions, and major public works projects. He went on to serve as an ambassador to Austria and earned the Navy Cross after his yacht was commandeered to spy on the Germans.

A Naval destroyer once bore the family name.

Despite his wartime heroics, Earle IV had big shoes to fill back home. He volunteered as a test pilot in the Naval Reserve while pursuing a career in marketing and finance.

“And that’s when he was assigned to take these canisters out and dump them off of Atlantic City,” said George Earle V.

The son did not learn of his father’s secret flights for over three decades – once the elder Earle retired to a snowy town in Vermont around 1980 when his emotions would surface again.

“After a drink or two, you start thinking,” said the son. “‘Well, I remember I did it. You know, nothing ever came of that. I wonder what the deal was.’ And then you start writing letters.”

His father wrote to the Navy and federal agencies probing for information about the flights. What was in those canisters? Could it be harmful?

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency had been aware of low-level radioactive waste dumped by ships in that area over the years – waste created by the government and commercial reactors.

One official said close to 29,000 containers of low-level radioactive waste were dumped near the location Earle described. While leaks had occurred, none proved majorly harmful.

But the agency had never heard of planes dumping canisters into the ocean.

Meanwhile, the one organization that could answer Earle’s questions and quiet his fears stayed silent.

“[The Navy] wouldn’t reply to him or even acknowledge that this even happened,” said his son, Earle V.

That didn’t sit well.

“Dad had the personality that you really didn’t want to piss him off,” he said.

Subscribe to The Pulse

Frustrated, his father decided to tell his story to the Associated Press in 1981.

“I knew he wasn’t making it up,” the younger Earle said.

His father told reporters the flights weighed on his conscience; that he was unable to shake his potential culpability in what, for all he knew, may have amounted to environmental catastrophe.

Government officials took his claims seriously and promised to investigate further. But the Navy denied having any knowledge of the flights.

“The thing that bothered me was never getting a response,” Earletold a reporter then. “I don’t trust our government anymore … it just hushes everything up.”

George Earle IV died in May 1992 having never known what he helped bury at sea, or that the answers to his questions were carefully collected and waiting to be discovered.

Operation Crossroads

The year before Earle’s death, in 1991, a chemist named J. Hartley Bowen Jr. donated a collection of papers to the Chemical Heritage Foundation – what is now the Science History Institute in Philadelphia.

“The collection itself is about two linear feet,” said Patrick Shea, the chief curator at the Institute.

The Institute’s entire archive would span over a mile in length, but every so often Shea sifts through a few feet at a time to refamiliarize himself with material donated long ago.

That’s how he came across the material donated by Bowen.

“I just pulled it off the shelf to determine what was in there to get a better understanding of the collection. I just opened up folders, looked through pages, like I do on any other normal day, Shea said. “But it was just the contents of the collection which really caught my attention.”

As Shea read through the pages, the collection revealed answers to the test pilot’s questions: What was in those canisters? Could it be harmful? And a formerly classified story that started very publicly began to emerge – with something called Operation Crossroads, the first of many nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands following World War II.

“It was one of the most dramatic scenes from the entire age of nuclear testing,” said Keith Parson, a historian who co-authored Bombing the Marshall Islands: A Cold War Tragedy.

The Navy’s top brass wanted the tests to make a big splash.

Admiral William Blandy and other high-ranking Navy officials saw how the war ended – with two large radioactive bangs – and worried this new type of warfare could render their fleet and massive budget superfluous.

“There was the question of, well, if we can destroy a city with one bomb, couldn’t we destroy the mightiest fleet with one bomb? So Naval personnel began to come up with this idea of testing it on a fleet of ships to see what happened,” said Parsons.

Maybe the knowledge gained from bombing ships today could help fortify fleets tomorrow, the pitch went. Meanwhile, some scientists warned against the experiments.

“General Leslie Groves, who was the Army general who was in charge of the Manhattan Project, he saw the whole thing as just basically preposterous,” said Parsons. “He said right away, ‘Well, we already know the best protection against a nuclear weapon. Don’t be there when it goes off.’”

Many thought Operation Crossroads was little more than a catastrophically dangerous lobbying effort.

“There was much cynicism about it at the time, people were deeply skeptical, but the Navy got its way,” said Parsons.

Politically, the proposed tests presented an opportunity for a global demonstration of might – to show the world exactly what America’s newest weapons were capable of.

So, in July 1946, the Navy parked dozens of decommissioned ships and planes filled with equipment and animals in the Marshall Islands, territory seized by the U.S. two years prior.

The Marshallese were “persuaded” to relocate as hundreds of journalists and diplomats converged a few miles away to witness the making of a nuclear disaster.

“It was more a demonstration of incompetence than anything else,” Parsons said.

The first bomb missed its target and failed to impress in broad daylight.

“Someone described the awesome sound of an atomic bomb as sounding kinda like a discreet belch,” Parsons said.

The second bomb, detonated beneath the water later that month, created a thick mist that exposed the entire lagoon to deadly radiation.

Little was learned. The animals burned. Many of the ships sank.

Still, the Navy took notes and measurements while a crew tried to decontaminate what remained afloat in the wake of the explosions. Various cleaners were unsuccessfully applied, even coffee grounds.

“They then needed to do scientific research to figure out what were the effects,” said archivist Patrick Shea. “As part of this Operation Crossroads, they took one of the planes that was on the deck of an aircraft carrier and they boxed it up and shipped that to Philadelphia to the Naval Yard.”

This is what J. Hartley Bowen’s donated collection detailed: the shipment and evaluation of a TBM-3E “Avenger,” a Navy bomber that had been exposed to nuclear blasts during Operation Crossroads.

It would not arrive in Philadelphia for testing until over a year after the blasts. At one point it was accompanied by an armed guard.

Bowen and his team had renovated Building 518, a small cleaning and stripping shop at the Navy Yard where the plane would be deconstructed and tested.

New toilets, ventilation systems, and washstands with clocks overhead were installed. Open windows and gaps were fitted for screens.

“They were concerned with any types of openings in the building because the birds could then get mixed up with the radiate radioactive waste,” Shea said.

The team spent months deconstructing the plane while trying to ensure the nearby Delaware River remained uncontaminated.

“They were examining everything. They were taking all the dials out of the cockpit and seeing if the dials still work. They were pulling the cushioning out of the seats to see if that had been affected by radiation. They tested every single part of that plane.”

During that time, J. Hartley Bowen took meticulous notes to inform the project’s final report. He was concerned with more than just the river and the plane.

“Personal health and safety issues appear quite often,” said Shea as he flipped through a folder. “They want to make sure the safety of the people and the equipment as well.”

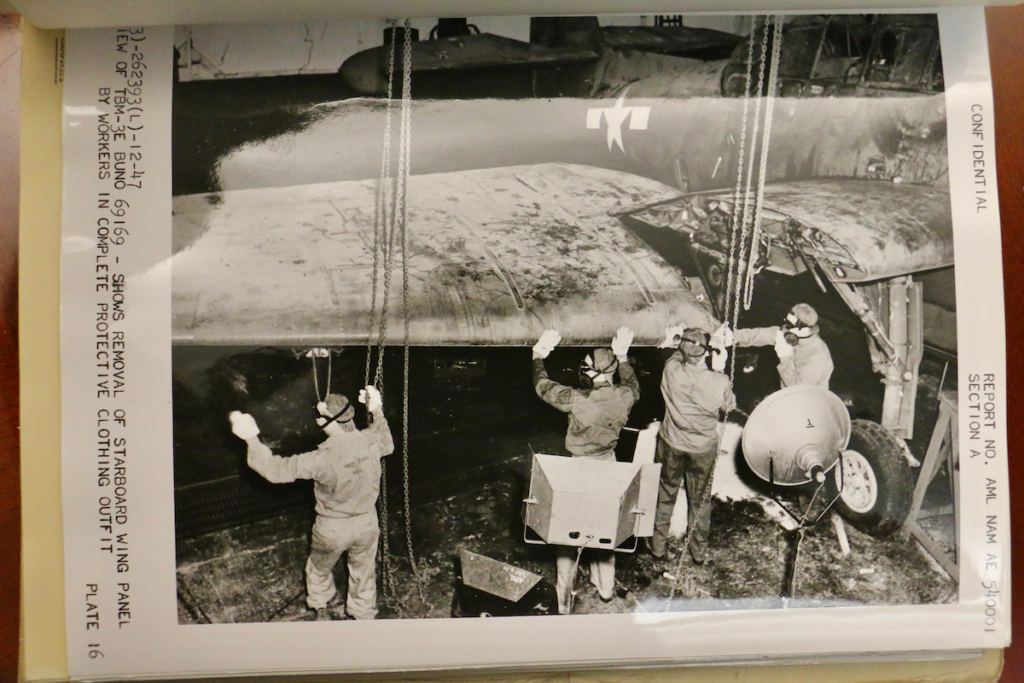

One aim of the project was to determine best practices for training personnel to handle material exposed to radiation – to “develop methods for the decontamination of radiologically active aircraft,” according to a memo from the now-defunct Bureau of Aeronautics.

The crew who worked on the project were themselves subjects on the frontier of radiological safety education. Their blood was drawn regularly, while clothes and protective gear were photographed and documented. The crew attended classes and were shown educational films.

“They said, ‘Look, when we provide uniforms to the workers, make sure there are no pockets because if they have pockets, they’ll bring cigarettes, they’ll bring food, they’ll bring things that they’re going to put in their mouth. And we can’t allow them to do that.’” said Shea. “It wasn’t that the workers were afraid. It’s that the workers didn’t know any better and they needed to be protected because it was the scientists who understood just how dangerous this actually was.”

But there were times when even scientists like Bowen were confronted with surprises.

Planning documents showed scientists believed the plane would be relatively safe for handling upon its arrival in Philadelphia. But according to handwritten logs, days after its arrival, some of the crew’s clothing quickly became too contaminated to wash and reuse.

It wasn’t a major problem, just unexpected.

“This laundry issue is something that keeps popping up right there,” said Shea. “They’re noticing that the workers’ gloves at the end of the day are getting contaminated. And there’s really nothing that they can do to decontaminate them.”

Bowen and his team needed to find a creative solution.

“Gloves found in excess of tolerance placed in drums for disposal at sea,” Bowen wrote.

Here, on faded graph paper, was the answer to George Earle IV’s questions.

“Monday, October 20th … dropped six barrels of contaminated waste at sea from B-17 location, approximately 100 miles east of Atlantic City,” another line read.

A black-and-white photograph included with the material captured the men loading these concrete-lined canisters onto the B-17.

Another shows the partially-dismantled test plane pitched over the side of a barge. It was sunk on July 27, 1949, at a depth of 300 fathoms 75 miles from the entrance of Delaware Bay.

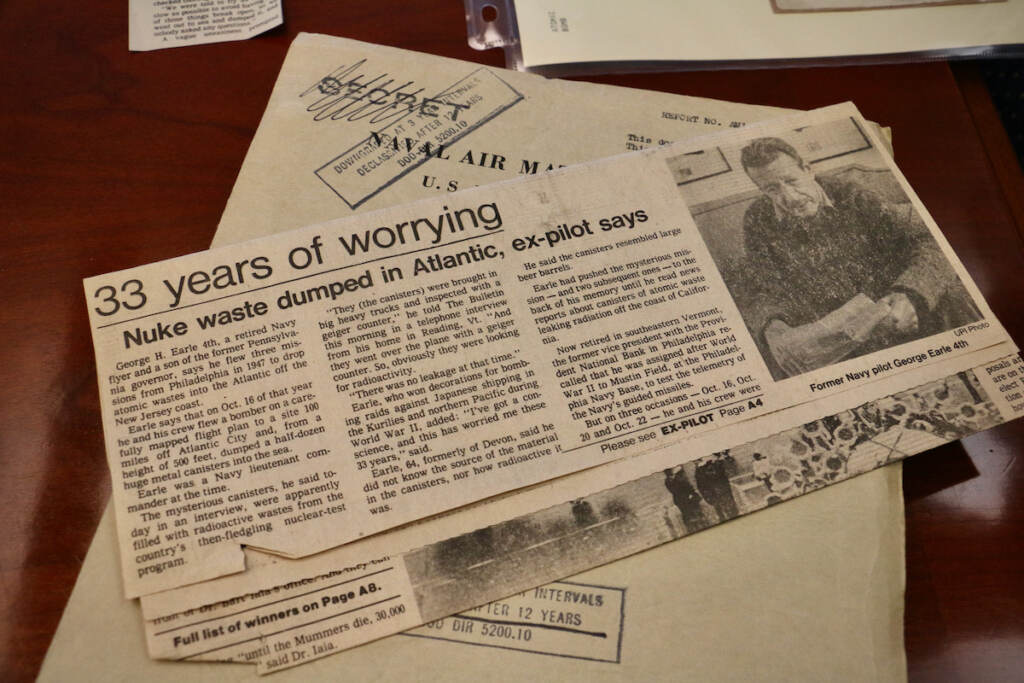

Bowen included another interesting addition to his donation: the newspaper articles from 1981 that first featured George Earle IV’s claims.

“This material was included with the collection. So, Bowen would have seen these and said, ‘Oh, yeah, we were definitely doing that,’” said Shea. “He cut them out and he put them with this material. So Bowen knew. He probably remembered George Earle. He was the one giving him orders to do all this. So he made the clippings and then he put it together with this material.”

Hartley Bowen Jr. died in 1999.

He knew what Earle buried at sea was likely not as dangerous as the pilot feared, but left no hint as to why he stayed silent on the matter long after the material’s classification expired, only to donate the records that confirmed the pilot’s claims years later. Bowen’s son could not be reached for comment.

Few insights into Bowen’s personal life remain.

In 1992, the year George Earle IV died, the chemist contributed an essay to a tribute of Robert Heinlein, a sci-fi writer who briefly worked at the Aeronautical Materials Laboratory, the same Navy department as Bowen.

He wrote fondly of Heinlein and mentioned his favorite novel by the author: “Friday.”

It was a curious choice, as most Heinlein fans seem to agree it’s far from the author’s best work.

Set in a dystopian 21st century, a secret agent for a quasi-military organization keeps a close eye on foes as she learns the true objective of her mission has been withheld from her.

In fact, she is the one being watched.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.