The federal government sells flood-prone homes to often unsuspecting buyers, NPR finds

An aerial view of flooded streets are seen in Helmetta of New Jersey. (Photo by Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

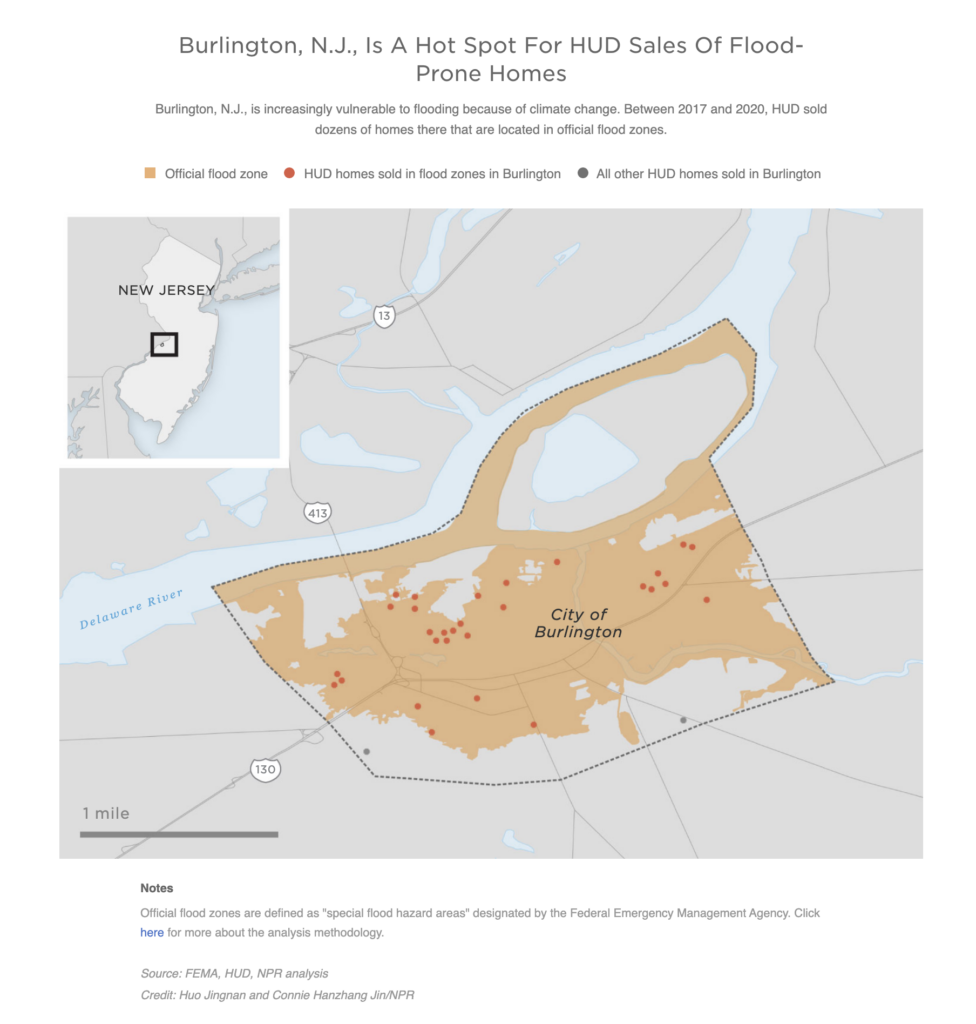

The first thing Larry McCanney fell in love with was the tree in the front yard. It cast shade on the porch of a house that, if he were honest, needed some work. But McCanney is handy, the price was right and the location was perfect, just a couple of miles from his childhood home in Burlington, N.J.

“We just kind of wanted to get our family started, and it was affordable for us,” McCanney says. “I’m still paying college loans off 11 years later, [and] we wanted to ensure that we were purchasing a place that, should I lose my job or if [my wife] lost her job, we wouldn’t be out of a house in two months’ time.”

There was one unexpected thing about the house: The seller was listed as the secretary of housing and urban development.

The homes that the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) sells are foreclosures. The previous owner was unable to pay their federally insured mortgage, and the house was seized by a bank and turned over to HUD. Only a small percentage of foreclosed homes in the United States end up being sold by HUD, but the numbers add up. Between 2017 and 2020, HUD sold nearly 100,000 homes around the country.

Like McCanney, many buyers are first-time homeowners excited to find a house they can afford. There is a nationwide shortage of affordable homes, especially for low-income families. Providing safe, affordable housing is HUD’s mission.

But an NPR investigation finds that the homes HUD sells are disproportionately located in flood-prone places, compared with Zillow records of all homes sold in the United States. The agency does not fully disclose the potential costs and dangers of living in harm’s way, and some of these transactions have happened as local governments are buying out properties in the same areas to mitigate flood risk.

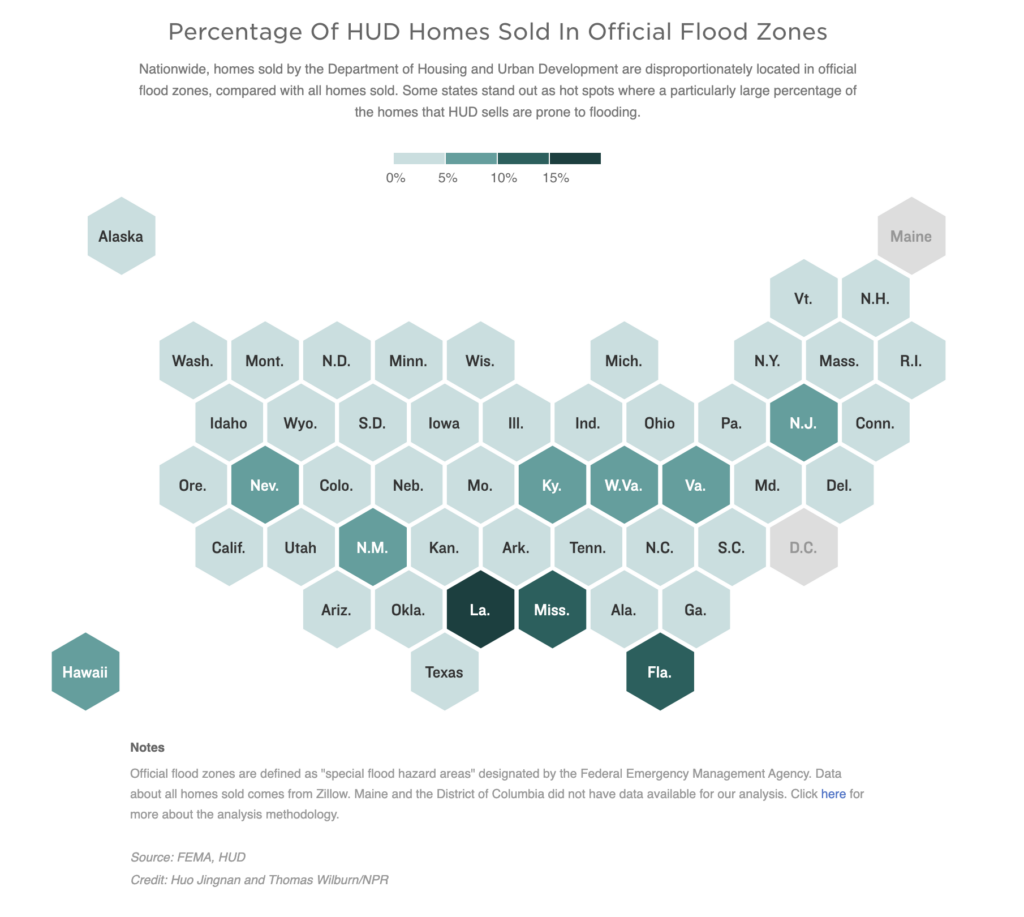

NPR analyzed tens of thousands of homes sold over a nearly four-year period and found that while HUD sells flood-prone homes in almost every state, a handful of states stand out as hot spots.

The findings include:

- Homes that were sold by HUD between January 2017 and August 2020 are in federally designated flood zones at almost 75 times the rate of all homes sold nationwide in that period.

- Louisiana, Florida and New Jersey stand out as hot spots. More than one-fifth of homes sold by HUD in Louisiana were in flood plains. In Florida, it was about 12% of homes sold by HUD, and in New Jersey, 7%. In comparison, Zillow’s records show that 0.1% or less of all homes sold in these states are in flood zones.

- In many cases, buyers of HUD homes get less information about flood risk and the cost of flood insurance than if they were to purchase the house from a private seller.

- Neighborhoods where HUD sold homes have lower median household income on average than areas where HUD did not sell homes.

Interviews with people who bought homes from HUD in multiple states make it clear that many buyers don’t learn that their houses are in an official flood zone until after they’ve made an offer or paid a nonrefundable deposit. And even if a house doesn’t flood immediately, the cost of managing flood risk can be significant.

There is no federal regulation requiring HUD to disclose flood risk to potential buyers. Most buyers find out their new house is prone to flooding when they are notified that they must purchase flood insurance, which happens so late in the homebuying process that it is often too late for families to back out of the purchase.

That’s what happened to McCanney. “That’s the one disappointment in this area. We’re in a flood zone, so we have to pay pretty expensive flood insurance,” he says. “I didn’t really take that into account when we first bought it.” This summer, a rainstorm flooded the park across the street and sent a foot of water into McCanney’s basement after his sump pump broke. McCanney says they’re eventually hoping to move to a house that’s not in a flood zone.

Housing and climate experts say the pattern of HUD home sales in flood plains raises questions about whether the agency fully appreciates the growing risks posed by climate change. And it suggests the housing agency may be inadvertently exposing families to catastrophic inundation, such as a foot or more of water in their home.

“This is an incredible insight,” says Laurie Schoeman, the resilience director for the national housing nonprofit Enterprise Community Partners, which manages affordable housing around the country. “It only bolsters the reality that a lot of homes that have provided shelter to low-income households are in areas of greater risk. These homes are in really vulnerable areas, and it puts households at risk.”

HUD spokesperson Michael Burns says one reason that HUD homes are disproportionately located in flood zones is that the agency does not choose the homes it sells and is likely to end up with homes that banks can’t or won’t sell because they are less marketable. Being located in a flood zone can make a home less marketable, he says, because buyers need flood insurance.

The agency is aware of climate-driven flood risks to homes, Burns says. “Millions of people in the United States live in areas prone to flooding, a threat that is only growing as climate change worsens,” he wrote in a statement to NPR. “Ensuring that federal agencies, including HUD, have the right tools and policies in place to increase resilience nationwide is a key priority of the Biden-Harris Administration for combating climate change and building strong, equitable communities.”

HUD does not disclose flood risk in its home listings

Many buyers of HUD homes don’t learn that their houses are in an official flood zone until after they’ve made an offer. That is too late in the process for many families.

A property’s flood risk needs to be disclosed early, when potential buyers are still weighing their options and before they make a deposit, as NPR has reported.

HUD could prominently display information on flood risk and the cost of flood insurance in its home listings. The underlying information is already available from a sister agency: The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provides the vast majority of residential flood insurance and publishes official flood maps.

But unlike real estate sites such as Realtor.com and Redfin, the official HUD Home Store website posts listings on the main page that buyers see without information about flood risk. Many HUD homes are cross-listed on multiple websites, but HUD specifically directs potential buyers to its website.

HUD did not respond to questions about why it does not include flood zone designations more prominently in the listings for the homes it sells.

Schoeman says HUD should work with real estate agents and local groups that often help market and sell HUD homes to make sure that the risk of flooding is clear from the get-go. Those groups could also help buyers understand how to mitigate flood risk — for example, by waterproofing a basement, updating yard drainage or raising the home’s foundation.

“We need to let people know, ‘Your dream house is wonderful, and here are the steps you’re going to need to take to protect it from flooding, because you’re in a flood zone,’ ” says Schoeman. “That’s the conversation we need to have. Not, ‘Here’s your house!’ And then you find out later after the first flood, ‘Oh boy, I’m in a really bad situation.’ ”

Low-income households have the most to lose

NPR’s analysis finds that the households in neighborhoods where HUD has sold homes are poorer on average than those in areas where HUD has not sold homes.

Long-term costs of flood damage can do tremendous harm to families, especially those who put their life savings into a home and live paycheck to paycheck. Low-income households are more likely to face health problems, displacement and bankruptcy after a major flood. In the long term, flooding can wipe out a family’s generational wealth by driving down home values or destroying homes altogether.

That worries some experts, who say HUD appears to be inadvertently concentrating marginalized people in risky areas and setting families up for big financial losses down the road.

Global warming is driving more frequent and severe flooding in much of the United States. Floods that used to occur once in a lifetime are now happening every few years in some places. NPR visited multiple neighborhoods in the Tampa Bay region, along Florida’s Gulf Coast, where HUD sold more than 100 homes between 2017 and 2020. In several of those neighborhoods in coastal Pinellas and Pasco counties, streets routinely flood even on sunny days due to sea level rise.

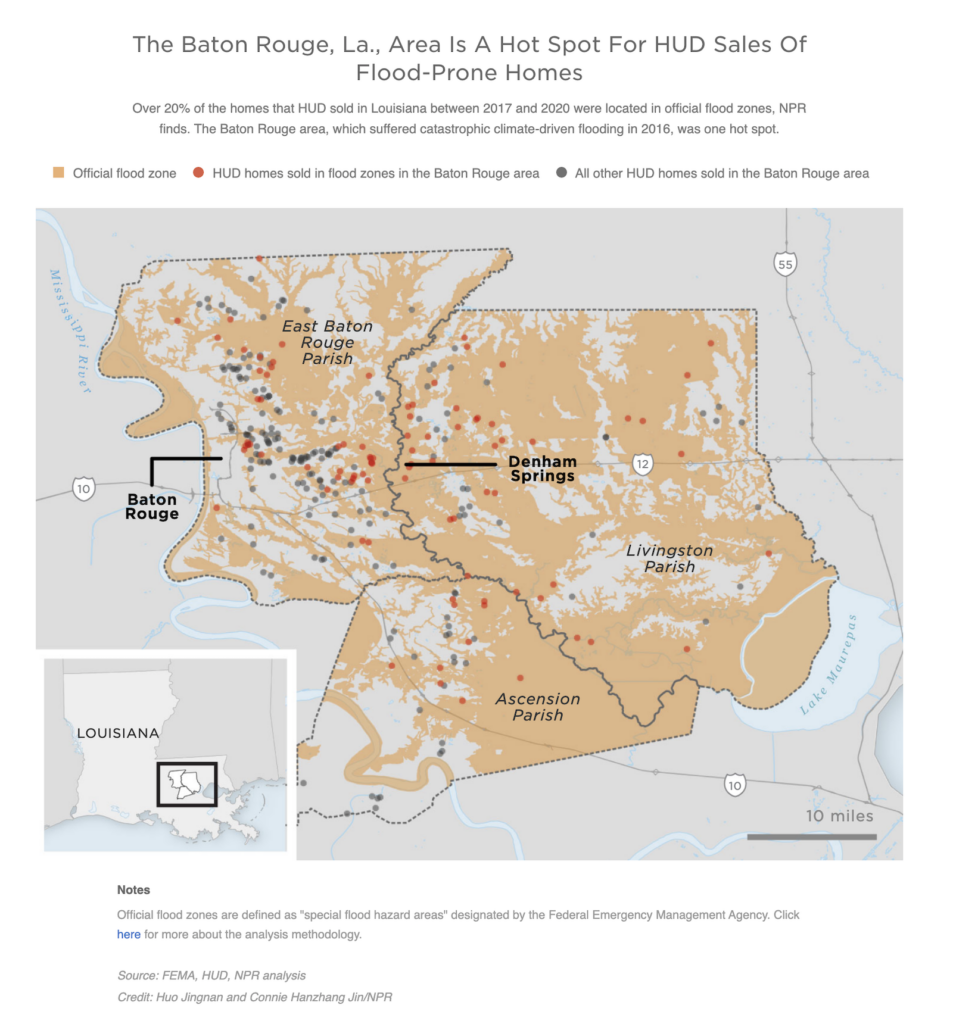

The threat of inundation — as well as the allure of affordable homes located in flood plains — is particularly clear in places that have suffered catastrophic flooding in recent years, like the area around Baton Rouge, La.

Jonathan Stewman bought his house in Denham Springs, La., in the spring of 2019. Homeownership was a lifelong dream, and he was excited to move in with his wife and two toddlers. They painted the porch and put in some new front steps. Now, they like to ride four-wheelers in the big backyard, and he’s building the kids a swing set.

Stewman grew up in an apartment in nearby Baton Rouge and always dreamed of having his own place, a family and a yard for the kids. “I never knew what it was like to stay in a house. So when I moved here, it felt like home immediately,” Stewman says.

Stewman works overnight shifts at a local refinery. He says they purchased the house for just $110,000. He wouldn’t have been able to afford anything more.

Stewman purchased his home just three years after a massive, climate-driven rainstorm dumped more than 20 inches of rain over the area in less than 24 hours. Stewman and his wife were told by their real estate agent that their house took in about 2 feet of water that day. But the benefits of the house seemed to outweigh the risks. “I got a good deal on it,” he says.

Baton Rouge, La., and its suburbs experienced massive floods in August 2016. In the years since, state officials have worked with the federal government, including HUD, to move people out of harm’s way. HUD simultaneously sold homes in official flood zones in the area. (Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images)

Still, he wants to be prepared for future floods. Stewman is saving money to raise the home at least another foot off the ground. “I have a family here, and I just want to make sure it is safe and secure at all times,” he says.

HUD should proactively help families like the Stewmans protect themselves and their homes, says Robert Bullard, a professor at Texas Southern University and a longtime environmental justice researcher.

For one thing, it’s a stated priority of the current administration. On his first day in office, President Biden promised to address climate change in an equitable way. This summer, the White House directed all federal agencies to examine whether their climate-related programs adequately serve marginalized communities, including poor people and people of color.

“HUD has to step up. No doubt about it. That equity lens needs to be applied to all of HUD’s policies,” says Bullard, who is a member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. “That’s not rocket science, but it means cooperating with other agencies.”

For example, HUD could work more closely with FEMA, which produces flood maps, provides flood insurance and allocates money for climate-related mitigation projects such as raising houses.

Burns, the agency spokesperson, suggests that infrastructure spending proposed by the Biden administration would “make housing more resilient for millions of families and … ensure communities are better prepared for future disasters.” HUD did not respond to specific questions about how it might work more closely with FEMA to reduce flood risk or how its home sales in flood zones might impact low-income buyers.

State and local governments criticize HUD

Some local officials say HUD needs to do a better job working with state and local agencies too, especially in places where homes have flooded repeatedly.

In many such communities, local officials are trying to move people out of harm’s way by purchasing homes and knocking them down. Demand for home buyouts has steadily increased in recent years, and the federal government helps pay for them through multiple programs, including one administered by HUD.

Officials in Louisiana have embraced home buyouts as a solution in the flood-prone state. Hundreds of homes are being purchased through state programs and demolished to create catchment areas in growing flood plains.

Pat Forbes is the director of the Louisiana Office of Community Development, which oversees buyouts and administers federal disaster-relief money through HUD’s Community Development Block Grant program. That program pays to elevate and flood-proof homes and to move people to higher ground.

“That’s incongruous with a lot of other directives coming from HUD, where we are not allowed to put folks in harm’s way,” Forbes says.

For example, after a 2016 storm flooded over 50,000 homes in and around Baton Rouge, the state offered buyouts. FEMA sent more than a thousand letters to residents, telling them that they needed to elevate their homes or move. The areas targeted for buyouts included the town where Stewman lives. NPR’s investigation found that HUD sold at least 19 homes in that town between 2017 and 2020.

In Florida, federal data obtained by NPR and member station WLRN show that four homes sold by HUD in Miami-Dade County are listed as “severe repetitive loss properties” by FEMA. Such properties have been flooded and rebuilt multiple times, at taxpayer expense. All together, the properties incurred nearly $500,000 in flood insurance payouts between 1999 and 2015.

Flagging them as “severe repetitive loss properties” is intended to reduce the cost to the federal government of repetitive rebuilding, as well as protect residents and prevent them from living in high-risk areas by prioritizing the houses for elevation or buyouts.

HUD did not comment on why it sells severe repetitive loss properties.

And local officials in other states echo the concerns raised by Forbes in Louisiana. The government of Roanoke, Va., has spent years trying to move families out of repeatedly flooded homes along a creek, only to have HUD step in and sell one of the houses to a new owner after it fell into foreclosure.

A similar dynamic has played out in Burlington County, N.J., where Larry McCanney bought his home. The county is extremely prone to flooding, and buyouts are an important part of the local government’s strategy for preventing repeat flood damage. Some of the funds for buyouts have come from FEMA and HUD, more evidence of how parts of the federal government are sometimes in conflict on climate change.

NPR’s analysis shows that HUD sold more than 30 flood-prone properties in the county between 2017 and 2020, including a house in a creek-side neighborhood where the county has actively tried to purchase repeatedly flooded homes.

Mary Pat Robbie has directed the county’s resource conservation department for 20 years and was unaware of the HUD sales. She says it’s frustrating that HUD never reached out to the county. If it had, perhaps the county could have stepped in to prevent a flood-prone home from changing hands.

“You’re really preventing that buyer of the house from dealing with the agony of having their property destroyed,” she says. Robbie has worked directly with many homeowners who survived floods in the county, and she says people often don’t understand how upsetting it is.

“I’ve dealt with a lot of homeowners,” she says. “They lost so much of sentimental value that they’re never going to get back.”

HUD did not respond to specific questions about how its home sales could affect home buyouts or how the agency works with local and state officials.

——————

Methodology: Through a Freedom of Information Act request, NPR obtained records of real estate owned (REO) single-family properties that HUD sold from January 2017 to August 2020. NPR cross-referenced the records with FEMA’s flood maps to identify homes in special flood hazard areas and also cross-referenced the records with American Community Survey data to analyze neighborhood characteristics of these homes. You can access NPR’s analysis and data here.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))