The 2020 election was a good one for Republicans not named Trump

Republican Sen. Susan Collins delivers election night remarks to supporters and staff on Nov. 3 in Bangor, Maine. Collins was down by four points in an average of polls before Election Day but won by 9 percentage points. (Scott Eisen/Getty Images)

Republicans outperformed the polls up and down the ballot in the 2020 election, to the surprise even of many Republican political operatives and survey researchers.

To be clear, Democrat Joe Biden defeated President Trump; Democrats will still control the House and still have a chance of picking up the Senate.

But Republicans made gains in the House — so far netting five seats (with 22 races not yet called). Given their presumed strength in the suburbs, Democrats had been expected to expand their majority.

That became increasingly likely the closer the election got — and not just because of public polls. That was also the expectation of Republicans, who conduct their own private polling and work on, run and advise campaigns.

In the Senate, Democrats have so far gained one seat, but they need three with a Biden win to take over the chamber. Democrats still have a chance of doing that with two runoff elections in Georgia. But that’s seen as possible, not likely.

It wasn’t expected to be this way. Democrats had put lots of Senate races in play, ones not expected to go their way at the beginning of the 2020 cycle, places like Kansas and Montana.

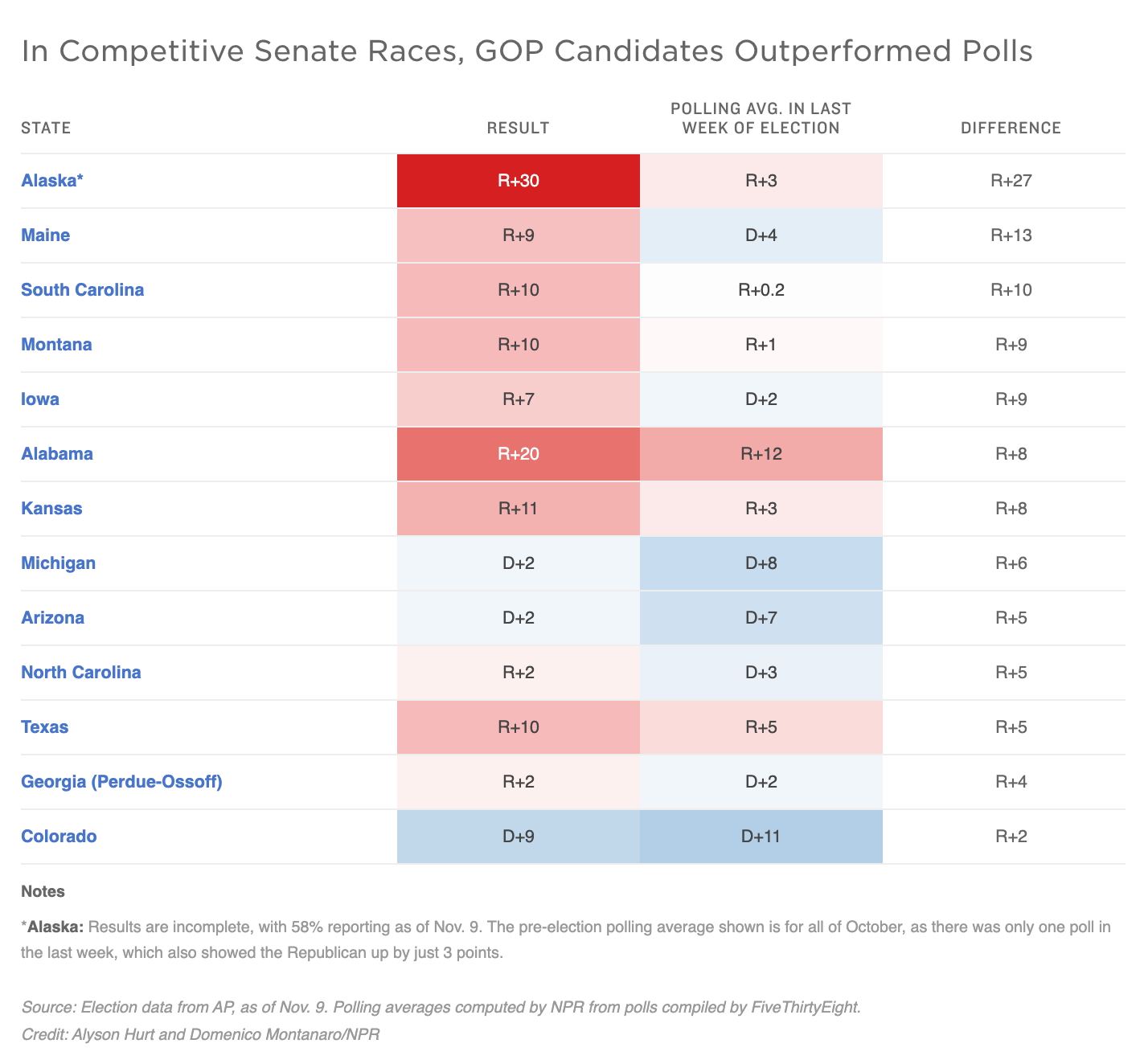

To be sure, many of the Senate races were expected to be close, perhaps with razor-thin margins, and a Democratic-controlled Senate was never an assured outcome. But when you look at the average of the polls in the last week of the election versus the ultimate result, it’s clear that Republicans were underrepresented all across the country.

All of these races, except Colorado and Alabama, were within single digits in the polls. Colorado, a state Biden won handily, wound up pretty close to the average. Alabama, a state Trump won by a lot, was an even bigger blowout than expected.

Many of the supposedly tightest races didn’t wind up tight at all. Maine is perhaps the most stunning one. Biden won the state by 9 percentage points, but Republican incumbent Susan Collins won re-election by 9 points.

Not only was Collins down by 4 points heading into Election Day in an average of the polls in the week before the election, but she led in one — ONE — poll in all of 2020. And that was back in July. That’s one poll out of almost three dozen.

In South Carolina, money flowed to Democrat Jaime Harrison, who looked like he actually had a shot of defeating incumbent Sen. Lindsey Graham. The Cook Political Report, which talks to the committees that help elect the candidates in each part, and others rated the race as a toss-up.

The polls seemed to bear that out, showing the race even. But in the end, it wasn’t even close. Graham won by 10 percentage points. It was always going to be tough for a Democrat to win statewide in South Carolina in a presidential year.

Alaska’s margin could tighten with mail-in votes still out and only 58% of the votes in, so put an asterisk next to that one, but that was supposed to be a 3-point race.

There is going to be a reckoning — again — within the polling industry. Survey researchers are already combing their numbers for patterns of what went wrong.

Some theories at this point include:

Early voting: Surveys having too many people in their samples saying they would vote early. The pollsters had a tough time adjusting for that, because there’s no historical trend to go by;

Democratic overresponse: Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents seem to have been more willing to talk to pollsters, and pro-Trump Republicans just didn’t want to participate as much because of their deep distrust of and disdain for the polls and the media.

This is not the idea of a “shy” Trump voter. While survey researchers — Democratic, Republican and nonpartisan — all found people less willing to say they are Trump supporters to their friends and families, especially women, they have found little evidence they aren’t telling pollsters they support the president.

The bigger problem may be Trump supporters simply not wanting to participate at all. That would seem to make sense, considering the consistent underestimation of Republican vote, especially in Republican-leaning states.

A Trump phenomenon: The other thing that is tough to quantify is whether this is something unique to when Trump is on the ballot. He has vilified polls and the media to a far-greater extent than any other presidential candidate. Supporting the idea that this was simply a Trump phenomenon is that polls were right in the 2018 midterm elections and nearly every special election in the last four years.

These are just early theories, but it’s probably going to be best practice to put even less stock in horse-race polling as an exact science, and to use rough, more artful measures, including demography, ad spending and private campaign poll reporting to find out where the campaigns think is important and where a candidate may or may not have a shot.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))