The story of Fred the mastodon, who died looking for love

A cast of the Buesching mastodon at the University of Michigan. (Eric Bronson/Michigan Photography)

The story of Fred the mastodon ends in a violent tragedy.

He was born more than 13,000 years ago somewhere in the Midwestern United States, and likely spent much of his early life at home, close to his family. But at one point in his adolescent years, it came time to leave his family and forge a path of his own.

For the rest of his life, Fred roamed what is now Indiana. Every summer, he’d compete against other males for a mate. These competitions were violent, physical battles, and one summer, one of these fights brought Fred to an untimely end. Dead at 34 years old, Fred’s body sank into the swampy earth.

These days, Fred’s huge skeleton is preserved in the Indiana State Museum. And his tusks were recently the subject of a research study tracing his life. By analyzing the chemical compounds in his tusks, a team of researchers was able to construct a detailed account of Fred’s seasonal migration patterns.

Josh Miller, a paleoecologist at the University of Cincinnati, was one of the researchers who co-authored the paper studying Fred. Also known as the Buesching mastodon, named after the family farm on which his remains were discovered, he is a distant relative of the modern elephant.

Miller said swamps were particularly good for preservation, which made Fred a unique research opportunity. “He has beautifully preserved bones, beautifully preserved tusks, and that really provides a beautiful opportunity to do this kind of work,” he said.

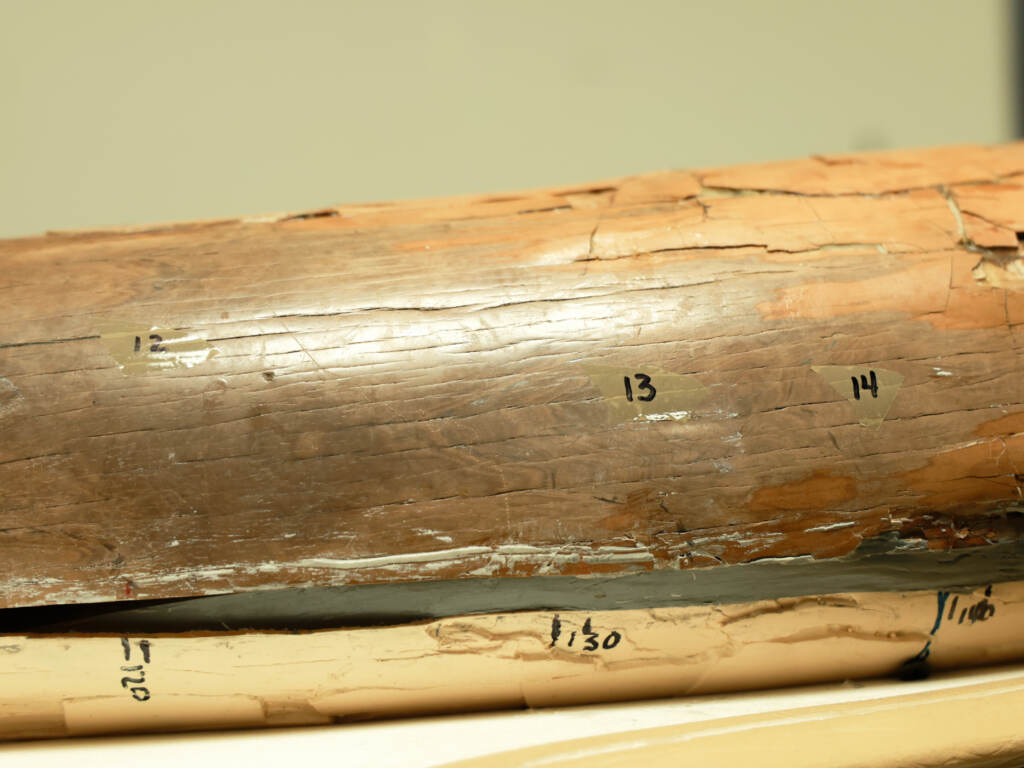

Mastodons’ tusks grow in distinct layers – similar to the rings on a tree trunk. As a result, the nutrients that build the layers of Fred’s tusks can tell us a lot about where he was at different points in his life. These layers store a daily record of Fred’s behavior, Miller said.

The team focused their analysis on the variations in two elements in particular: strontium and oxygen. “Every element comes in different isotopes – kind of different flavors, if you will – isotopes that weigh slightly more or slightly less,” Miller said.

Strontium isotopes are the key to understanding where geographically Fred spent his life. The underlying geology of landscapes across the region contain different ratios of strontium isotopes, and they seep into the water and plants in that area.

Oxygen isotopes tell us the season Fred was in any particular region. Different oxygen isotopes are more or less prevalent during each season, giving the researchers insight into the the timing of Fred’s migration patterns.

These two isotopes are faithfully recorded in Fred’s tusks. Then, with some statistical modeling, Miller and his team could pinpoint where and when each piece of Fred’s tusks grew.

When he was young, Fred would have stuck close to home with his herd, and grown a lot. But then there’s a year in which Fred’s growth is stunted – that’s when Miller’s analysis stars.

Miller predicts that like modern male elephants, Fred was kicked out of the herd once he grew up to be a nuisance to his family, explaining the reduced growth.

“They’re essentially just really obnoxious, and they’re just getting in everyone’s hair,” Miller said. “They’re just not particularly helpful members of the herd. And at that point, the mom, the aunts, will essentially boot that individual from the maternal herd.”

After Fred set off to fend for himself, his tusks reflected his travels. Every summer, he would return to Northeastern Indiana. Miller predicts this was Fred’s preferred mating ground, because around this time, his tusks start to show signs of battle.

When they’re competing for mates, mastodons get into huge battles where one or even both combatants may die, Miller said. Their tusks are their primary weapons, and one summer, an opponent stabbed his tusk through Fred’s skull.

The injury killed him, bringing the story of Fred to an end.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))