Parents are scrambling after schools suddenly cancel class over staffing and burnout

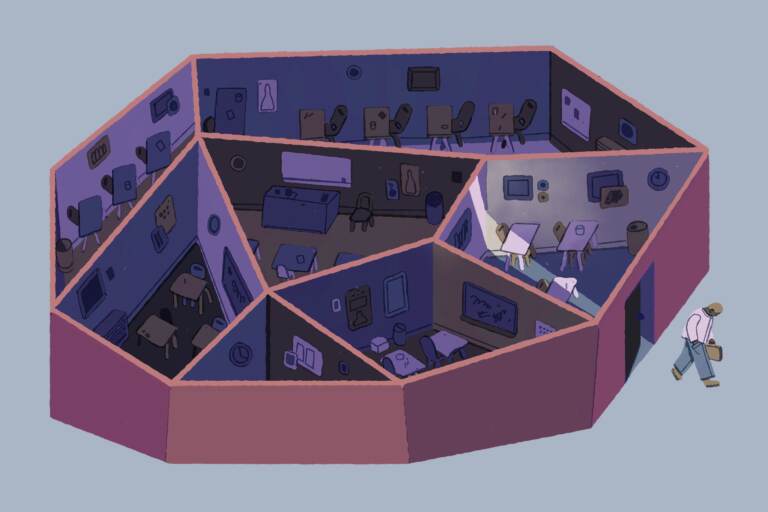

School districts around the country have been announcing extra days off this fall to address staff shortages and mental health. For some families, the unpredictable schedule feels like a betrayal. (Sam Rowe for NPR)

Two weeks notice: Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools in North Carolina voted on Oct. 28 to close schools on Nov. 12, for a “day of kindness, community and connection.”

Five days notice: On the evening of Wednesday, Nov. 17, Ann Arbor Public Schools in Michigan announced they would be closed the following Monday and Tuesday, extending Thanksgiving break for a full week. The district cited rising COVID-19 cases and staff shortages.

Three and even two days notice: On Tuesday and Wednesday, Nov. 9 and 10, three different districts in Washington state — in Seattle, Bellevue and Kent — announced schools would be closed that same Friday, the day after Veterans Day, due to staff shortages.

Schools and districts around the country have been canceling classes on short notice. The cancellations aren’t directly for COVID quarantines; instead schools are citing staff shortages, staff fatigue, mental health and sometimes even student fights.

Burbio, an organization that tracks school district websites, says these closures are an accelerating trend in the month of November, affecting 858 districts and 8,692 individual schools so far. At least 20 districts have added days to their Thanksgiving break this week, as happened in Ann Arbor, according to a report by CNN.

Sudden changes to the calendar leave families scrambling to make alternate arrangements.

Parent Jennifer Reesman says, “We’re upset because it really is a slap in the face to all of those essential workers” who are parents. Reesman works in healthcare, in person, and is a single mother of a daughter in Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland. Her district canceled the half day before Thanksgiving with two weeks notice.

Underscoring the extreme feelings this brings up for some families, she adds, “Granted, it’s only a half day … but talking with other parents, we all feel like we’re witnessing the death of public education up close and personal.”

Schools are struggling with staff shortages and fatigue

School leaders say they are between a rock and a hard place. Alena Zachery- Ross is superintendent of Ypsilanti Community Schools, in Michigan. She announced earlier this month that they were taking the full week off for Thanksgiving.

She says her staff got no summer break, since about a third of the district’s students came for extended summer school. Now that they’re back full time and in person, students have lots of work to do adjusting to classroom routines. COVID-19 protocols also take extra time. It’s all piled on.

Staff told her they were coming home and going directly to sleep, and spending entire weekends recuperating. “They were spent,” Zachery- Ross says.

The custodial staff has 800 hours of accumulated overtime, she explains, and still they can’t keep up with the demand for cleaning and disinfection.

Districts do have federal COVID relief money that could presumably be used to address staff shortages. But those funds expire in three years, which means school leaders in some places may be reluctant to commit to raises or hiring for brand-new roles.

In Washington state, Janine Thorn is chief communications and engagement officer with the Bellevue School District. She also has a child in the district, and she says her husband had to take off work to be with him when schools closed on Nov. 12, after Veterans Day.

“I realize that it is a privilege to have an additional parent in the household to take off work,” she says. “That is a recognized hardship on single parents or households that are not able to do the same.”

But Thorn says Bellevue had no choice but to close. Many staff put in for paid time off the day after the holiday. And because of social distancing rules, they can’t put two classes with one teacher.

Like districts around the country, “we’re currently hiring for food service workers, transportation, nurses,” she says. The district’s website lists dozens of job openings.

Thorn says the district partnered with the Boys and Girls Club to offer families free child care, including meals, on the day off. And they added an instructional day at the end of January to make up for the lost day — something not every district is doing.

“There is an undeniable desire to make sure that kids get as much in-person instruction as possible,” she says. “Families believe in that and our educators also want that for our students.”

Keeping schools open can take extreme measures

Like other districts in the Seattle area, many of Highline Public Schools’ staff put in for paid time off on Friday, Nov. 12, the day after Veterans Day.

But Highline was ready. They have raised their substitute teacher day rate by $65 to $240, one of the highest in the region, so they had the extra coverage they needed.

“It’s an all-hands-on-deck situation,” says Superintendent Susan Enfield.

And she means all hands. She got her Washington state substitute teacher credential in case she needs to cover classes personally, and school board members have volunteered to step in too.

“I love me a long weekend as much as the next person,” Enfield says. “I get it that my staff is tired. But for families, many of whom are working multiple jobs, and if they find out with two days’ notice that they have to find childcare, that’s not an easy lift.”

For families, sudden closures range from a minor inconvenience to a major betrayal

Parents across the country responded to an NPR tweet asking how these closures have affected their families. Some agreed that the closures could help reduce COVID spread. Some were also sympathetic to the idea that school staff needed a break.

“Overwhelmingly, I think our community supports the needs of our teachers,” says Cassie Ford, president of the PTA at Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools in North Carolina, which announced their extended Thanksgiving break in late October.

Other parents were livid.

Tabbatha Renea, a single mother of a first grader in Ann Arbor, fired off an email to the superintendent that she shared with NPR:

Do you care at all about my child progressing with reading, writing, math, social skills, etc? Because I do. It’s not just about finding childcare. I can typically send my kid to sit in front of the tv at her Grandma’s house, but her Grandma can’t do homeschooling work with her…

My child… a young Black girl, raised by a single mom alone, a parent who doesn’t hold a bachelor’s degree. Consider those facts and the statistical disadvantage they put her in.

Then consider the fact the decisions AAPS is making, that you are making, are ADDING to the uphill battle she and her mother have to fight to ensure she can be successful later in life. I hope you lose sleep over it the way that I have for the past 1.5 years and that I continue to.

When NPR asked the district for comment, a spokesperson shared the superintendent’s public statement, which read in part, “I understand that this week-before notice will pose challenges for some of our families, and I sincerely apologize for this situation.”

Ann Arbor Public Schools had previously canceled classes another day this month, Monday, Nov.1, announcing the schedule change the Wednesday before.

Parents wonder if they can still count on public schools

Earlier this month, Jennifer Reesman, in Maryland, attended a school board meeting, in person, on her lunch break to speak in favor of the district using a COVID “test to stay” policy in order to limit quarantines and thus lost school days. Then, suddenly, the board voted unanimously on a last-minute agenda item: to cancel the half day of school before Thanksgiving.

“And sitting there in the audience as a parent, it really hit me that I … and everybody in our community can no longer count on the public schools. And I feel like after the last year and a half, there was a lot of that sentiment that this is just not something we can count on.”

In response to a request for comment, Montgomery County Public Schools shared the video of the Nov. 9 board meeting, where Interim Superintendent Monifa McKnight said: “The staff has worked incredibly hard this year to support the transition” back to in-person school, adding that teachers have lost planning time because they had to cover others’ classes due to a shortage of substitutes.

Students with disabilities need all the class time they can get

Reesman is also a pediatric neuropsychologist. She says that while many students may enjoy a day off, the patients she works with are different.

“For children with severe and significant disabilities, having unexpected time off or a change to your schedule unexpectedly is a lot to handle. And I really feel for those kids and families that are missing out on needed speech and language therapy, or occupational therapy or physical therapy that’s received in the school, because those kids are making progress and really every hour counts that they’re in the building.”

Experts worry about what closures mean for the future

Robin Lake is the director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education. Her organization has been tracking the COVID responses of 100 of the largest and most prominent school districts in all 50 states.

She says the trend of taking four-day weeks started before the pandemic, and has been accelerating. As of last spring, about two-thirds of the districts in their sample were doing four-day weeks “under the guise of deep cleaning,” she says.

In mid-November, Detroit schools announced they’re going virtual for Fridays in December, mentioning both mental health and “time to more thoroughly clean schools.” Then on Friday, Nov. 19, with just three days’ notice, they further canceled classes for the Monday and Tuesday before Thanksgiving, also citing “cleaning and sanitization.”

And yet, in April the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention relaxed its previous guidance on disinfecting buildings, in recognition of the evidence that COVID-19 is rarely spread through surfaces.

Lake is worried about students who may be on the verge of failing out or dropping out of school. “Those who have disappeared or are close to disappearing, they need us to be pulling them back, not pushing them out.”

And she’s dubious about the label of “mental health days.”

“Whose mental health are we talking about? We need to be really clear about that. We know that students have really struggled with their mental health in remote learning, the social isolation, time away from friends, away from supports for kids with special needs.”

Lake affirms that staff shortages and educator stress are real. “What I want to raise is whether we can support teachers’ mental health and keep kids in schools. I think we can … I think we’ve gotten into this mode of, every time things get hard, our answer is closed school. That’s really problematic.”

School closures give some flashbacks to March 2020

On Thursday, Nov. 4, Chicago Public Schools announced Friday, Nov. 12, would be a “Vaccination Awareness Day,” canceling classes with just over a week’s notice.

Kathryn Rose wasn’t impressed. She’s a parent of three Chicago Public School students as well as a substitute teacher in the district, where she sees schools scrambling to cover frequent staff absences. The district recently pledged to spend $10 million addressing its staff shortages.

Rose sees the “abrupt” closure as part of a trend: early dismissals, and Wednesdays designated “catch-up days” in some schools, with no new material introduced. Little things? Perhaps, but they add up.

Chicago Public Schools did not respond to NPR’s request for comment.

“I think that it’s just the unraveling of mandatory five-day-a-week instruction,” Rose says. “It began with COVID-related disruptions over the last two years, and now the idea of universal public schooling has been undermined.”

The fear of repeating 2020 was mentioned by a lot of the families NPR spoke with. It made these closures seem symbolic of more than a passing inconvenience.

Mira Schwarz, 17, is a senior at Community High School in Ann Arbor. While she says she has “senioritis” and can see the appeal of a day or two off, she and her friends also see that COVID cases are creeping up. They wonder what will happen to the rest of their school year.

“We were all talking about, like, ‘It feels like March 13th again. Are we going to come back?’ I can’t do virtual again. That’s what they said last time, right? They said only one extra week, you know, only a couple of days. And then we were gone for the rest of the year.”

Surprising even herself, she says she would rather be at school.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)