Pandemic or no, kids are still getting — and spreading — head lice

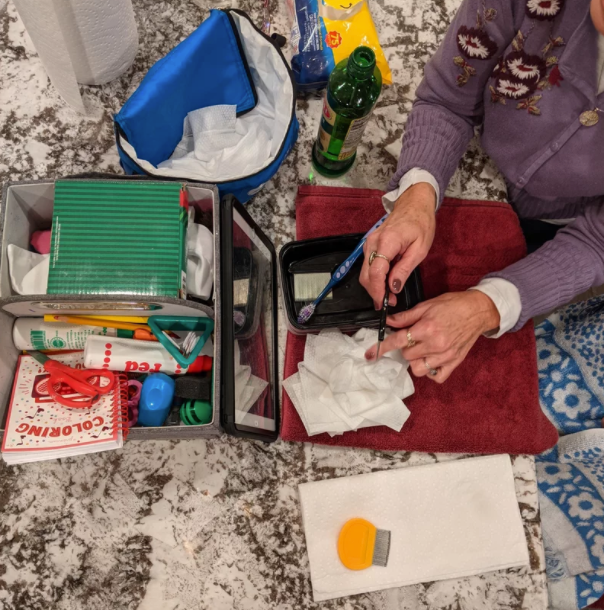

LiceDoctors technician Linda Holmes checks the heads of everyone in the Marker family for lice, including preschooler Hudson. It cost more than $200 to get the four-person household checked — eyebrows and Dad’s beard included. (Rae Ellen Bichell/KHN)

The Marker family opened their door on a recent evening in Parker, Colo., to a woman dressed in purple, with a military attitude to cleanliness.

Linda Holmes, who has worked as a technician with LiceDoctors for five years, came straight from her day job at a hospital after she got the call from a dispatcher that the Marker family needed her ASAP.

According to those in the world of professional nitpicking, Pediculus humanus capitis, the much-despised head louse, has returned.

“It’s definitely back,” said Kelli Boswell, owner of Lice & Easy, a boutique where people in the Denver area can get deloused, a process that can range from minutes to hours depending on the method and the infestation. “It’s a sign that things are coming back to normal.”

Colds and more serious bugs like respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, are also back. That may leave some to wonder: With all the COVID prevention measures in place, how are kids sharing these things?

Like the coronavirus, all these bugs depend on human sociability. Unfortunately, the measures that many reopened schools have taken to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 — masks, hand-washing, vaccination — do little to deter the spread of the head louse. However, physical distancing, such as spacing desks 3 feet apart, should be helping, if it’s actually happening.

Lice are, in theory, harder to spread than the SARS-CoV-2 virus because proximity alone isn’t enough: They usually need head-to-head contact. If a kid gets lice, odds are it means that kid spent some quality time close enough to another kid for the parasite to make its move. (Researchers tend to agree that transmission via inanimate objects like combs and hats is minimal.)

The head louse is not known for its fortitude or athletic prowess. It’s basically the couch potato of pests. Adults can’t survive more than a day or two without snacking on blood. Their eggs can’t hatch without the warmth of a human head, and will die within about a week if not in those cozy conditions. The bugs can’t jump or fly — only crawl. The one thing going for the head louse is its highly specialized claws, evolved to grasp human hair.

Unlike the body louse, the head louse isn’t known to spread disease. An infestation doesn’t indicate anything about a person’s hygiene. (In fact, the lore of delousers says that the bugs prefer clean hair because it’s more grabbable.) And despite common misconceptions, they can colonize people of all ages, races and ethnicities.

COVID lockdowns were not great from a louse-world-domination standpoint. But the critters have been bonding with us for tens of thousands of years. A little lockdown wasn’t going to end the romance.

Federico Galassi, a researcher with Argentina’s Pest and Insecticide Research Center, found that strict, early COVID lockdowns did, indeed, lead to a decline in head lice among kids in Buenos Aires, but the bugs came nowhere close to being eliminated. His study found prevalence dropped from about 70% to about 44%.

And one thing is clear: When people shut their doors and hunkered down in early lockdowns, the lice were right there hunkered down with us. When SaLeah Snelling reopened the doors of her Lice Clinics of America salon in Boise, Idaho, in May, she said, “the cases of head lice were heavier than we’ve ever seen.” And it wasn’t just one or two people in the household with lice, but the entire household.

Now, Galassi and American louse workers say, infestation rates are back to pre-lockdown norms, despite school COVID-19 protections.

Nix, a brand of anti-louse products, publishes a map that claims lice are bad right now in Houston, most of Alabama and New Mexico, plus Tulsa, Oklahoma. The map directs people to locations that carry its products since many parents use a DIY approach once they spy the critter on a child’s head.

Richard Pollack, chief scientific officer with pro-bono pest-identification service IdentifyUS, said most claims about louse prevalence are “marketing nonsense” from a largely unregulated industry focused on apparent infestations that often turn out to be just dandruff, glitter, hair spray, grass-dwelling springtail insects, innocuous fungus or even cookie crumbs.

It’s possible that the recent increase in business for professional nitpickery suggests that people are now comfortable seeking help outside the home rather than it being a sign of a surge in the bugs.

While little research exists to confirm if there is a real rise in lice, Boswell, Pollack and even the National Association of School Nurses agree that the bugs aren’t likely spreading in the classroom because in-school louse transmission is considered rare. Instead, Boswell said, it’s more likely that as other activities resumed — sleepovers, play dates, summer camp, family gatherings — the bugs prospered once more.

Pollack once wrote in a presentation slide, “Head lice indicate that the child has friends.”

Preschoolers tend to get the infestations the most “because they’re more cuddly,” said Julia Wilson, co-owner of Rocky Mountain Lice Removal in Lafayette, Colorado. But she has also noticed a rise among teenagers, which she ascribes to them taking selfies with pals.

“You say to them, ‘Have you touched heads?’ and the teenager’s like ‘No, never,'” said Wilson. “And then all of a sudden, they’re literally taking a selfie photo with their friends.”

The Marker family isn’t sure where third grader Huntley’s lice originated. Perhaps a close friend or her dance team? The Markers spent more than $200 to get the four-person household checked — eyebrows and Dad’s beard included. Her dad and her preschool-aged brother were free of nits. But Holmes did find a couple of nits on Huntley’s mom, Paris.

“You can just burn my whole head right now,” said Paris.

After combing each head carefully, Holmes ended the session by hugging her customers goodbye, proof that she trusts her work.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is an editorially independent programs of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation).

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)