Most of nation’s top public universities aren’t affordable for low-income students

Tallulah Fontaine for NPR

America’s top public universities, known as flagships, are generally the most well-resourced public universities in their respective states — think the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor or the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. They’re rigorous schools, and many were built on federal land grants meant to serve the “industrial classes.” Today, only four public flagship universities are affordable for students from low-income families, according to a report from the Institute for Higher Education Policy.

Access to public universities can be critical for low-income students because those institutions can serve as engines for upward mobility. And these schools aren’t living up to their responsibility to remain affordable, says Mamie Voight, one of the study’s authors from IHEP.

“They are a public institution. They are funded by state taxpayer dollars,” she explains. “They have an incredibly important role to play in both preparing the workforce for tomorrow and educating the workforce for tomorrow.”

While the definition of what makes a school a flagship is a little murky, many are the main campus of a larger statewide system. Flagship universities receive almost 40% more state funding per full-time undergraduate student than other public four-year schools. They also tend to have higher graduation rates.

A combination of factors makes many of these schools unaffordable for low-income students. State funding for higher education suffered big cuts during the Great Recession, which contributed to tuition increases. Another factor: The federal Pell Grant program, which helps students “who display exceptional financial need,” hasn’t kept pace with the increased cost of college. In many states, need-based grants and scholarship aid awarded by the state and public institutions don’t make up the difference.

How to be affordable

A huge part of staying affordable is prioritizing need-based aid at the state and institution levels, according to some of the most affordable schools in the study, such as the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“There is a strong commitment here to really considering affordability and accessibility as part of that public mission,” says Rachelle Feldman, UNC’s associate provost and director of scholarships and student aid.

UNC has the Carolina Covenant, a need-based program that uses grants, scholarships and a work-study jobs to cover college costs, including living expenses. The University of Wisconsin-Madison has a similar program called FASTrack.

Both universities say their financial aid programs have helped them recruit more diverse classes. “We not only would be a less diverse school if we weren’t focusing on need-based aid — we’d be a weaker school because the students who enroll here with need-based student aid earned the right to be here,” says Stephen Farmer, UNC’s vice provost for enrollment and undergraduate admissions.

But even at a school that’s affordable for low-income students, there may not be many of them on campus. Among the 10 most affordable flagships in the study, half had “extraordinarily low enrollment rates” of low-income students. That could be because of recruitment priorities and practices at the institutions, according to the report.

Fewer than 15% of UW-Madison’s students receive Pell Grants — that’s about half the 30% rate at comparable four-year college campuses nationally. “We recognize that there’s much work for us to do to ensure that students … see UW-Madison as an institution that’s accessible and affordable,” says Derek Kindle, the school’s director of student financial aid.

Obstacles to affordability

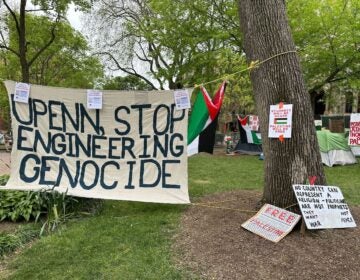

Pennsylvania State University ranked among the least affordable flagships. It suffers from a lack of funding from the state; Pennsylvania ranks among the worst in higher ed spending per capita.

Penn State awards need-based aid on a case-by-case basis, according to Wyatt DuBois, a spokesperson for the school, which he thinks may have affected its rankings in the IHEP study.

The report calculated affordability by using the net-price calculator on each school’s website. Schools that awarded more aid based on lower income or demonstrated financial need ranked higher on affordability.

But the calculation isn’t that simple, says Sandy Baum, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, because affordability is actually more of a continuum. Affordability, she says, is “not really a yes-or-no question. It’s not like if something is $100 more expensive, suddenly you can’t afford it,” she says.

The study also didn’t measure students’ ability to take out loans. Depending on what career students go into — and estimating the salary they’ll eventually make — some students may be able to afford to take out more student loans than others.

“If you’re going to study early childhood education and what you really want to be is a preschool teacher, then you can’t afford to borrow as much as somebody who’s studying electrical engineering who’s likely to earn more money,” Baum says.

But what about tuition? Baum acknowledged that tuition rates are high and outpacing need-based aid, putting a quality college education out of reach for many low-income students.

“Need-based aid has gone up but not enough,” says Baum. “And so it is harder and harder for students and families to pay.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))