Medicaid renewals are starting. Those who don’t reenroll could get kicked off

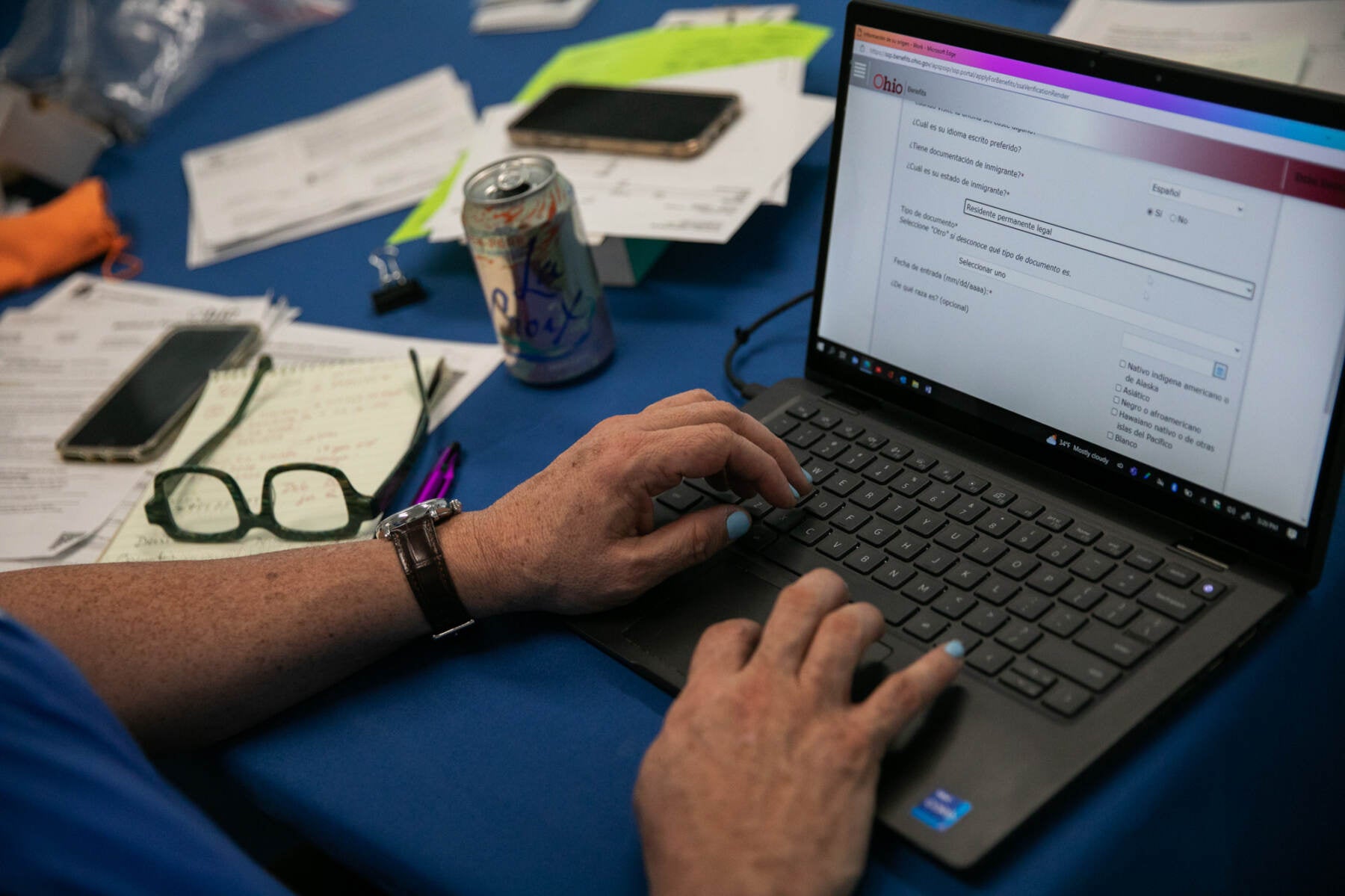

Samuel Camacho, a health insurance navigator with the Universal Health Care Action Network of Ohio, assists people in enrolling for or renewing Medicaid. (Maddie McGarvey for NPR)

Dominique Jackson has been on Medicaid for seven years. But the Columbus, Ohio, resident didn’t realize he’d have to verify his eligibility every year to keep his coverage. Then, he sprained his ankle.

“I found that I had to re-enroll because I went to the emergency room and I still had my old Medicaid card. And when they scanned it, it came up that I was no longer under that provider,” Jackson recalls. Luckily, he was able to work file the paperwork and get his care covered.

For the past three years, Jackson and tens of millions of other Americans on Medicaid haven’t had to worry about keeping their coverage. That’s because early in the pandemic, Congress passed a law that prevented states from dropping people from their Medicaid rolls.

“That’s been really huge, because you don’t want to find out that you don’t have your Medicaid when you’re in the emergency room, especially during a pandemic,” says Kathryn Bamberger, who heads up a team of health insurance navigators at Southeast Healthcare, a health center serving low-income patients throughout central Ohio.

This was one big reason behind historically high rates of Medicaid enrollment and an all-time low rate of people who were uninsured in the U.S. last year.

But those protections expire on March 31, which means that as of April 1, states can once again begin removing people from their Medicaid rolls. Estimates suggest that nationwide, between 15 million and 18 million people are at risk of losing their Medicaid coverage over the coming months.

That includes nearly 7 million people who remain eligible for the program but face barriers to filling out their paperwork in a timely manner, according to projections from the Department of Health and Human Services.

The renewal process “is going to hit everyone in the Medicaid program,” says Jennifer Tolbert, associate director for the program on Medicaid and the uninsured at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

But it won’t happen all at once. Tolbert says states have some leeway in how they restart the signup process. The majority of states plan to do it over a 12-to-14-month period, according to a report from KFF.

That could help what is bound to be a messy and difficult process. Re-enrolling is riddled with obstacles for enrollees – starting with the fact they may not even receive the notification that they need to do it, and including difficulties in obtaining the kinds of documentation required to prove their eligibility.

Fighting through a maze of paperwork

Ohio is one of eight states that began the renewal process in February, according to KFF, and it has already started sending out renewal notices. But Bamberger says people on Medicaid often get disenrolled, even if they are still eligible, because the state can’t reach them and they never respond to requests for verifications of household size or income.

“You’ve got a disproportionate number of people here who are not computer literate and whose housing is unstable,” Bamberger says, adding, “Just because I listed my friend as a mailing address three years ago doesn’t mean that that person’s going to keep my mail so that I can get it now if I’m homeless. [Or] what if that address is for your old girlfriend or boyfriend, and you haven’t spoken in two years?”

She notes that verifying documents can be tricky to get if your job doesn’t provide a pay stub or you work in the gig economy – for example, as a driver for DoorDash. “They get their payment information on their phone. It doesn’t look like a pay stub that somebody who’s working [a traditional] job in an office gets.”

Stephanie Jorgensen has experienced this frustrating process firsthand. “Gathering all of the verifications is like the most stressful part. It’s a job,” she says.

Jorgensen lives in Columbus, Ohio. She’s spent much of her career working in social services nonprofits. She’s also a single mother of two on Medicaid, and is currently unemployed while finishing a certification in graduate school. Yet despite her expertise, she says it’s a ton of work to navigate the system.

“I have a masters degree and it’s still like a fight every step of the way,” she says.

For example, Jorgensen has to provide documentation that she no longer works at a nonprofit that she left more than a decade ago, which has since closed up shop. “I can’t even get a verification from them stating that they don’t exist,” she says.

Still, Jorgensen is relatively lucky. At least she knows she has to renew her Medicaid soon. The majority of Americans enrolled in Medicaid don’t know they’ll need to act to keep their coverage, according to a survey released in February by the Urban Institute.

Most states are conducting outreach campaigns to encourage Medicaid recipients to update their address information, according to KFF. But Bamberger says the reality is, many people won’t realize they’ve lost Medicaid coverage until they actually need it.

“We fully expect in April for people to call us from the pharmacy,” Bamberger says. “That’s often where they learn that, ‘Oh, my Medicaid doesn’t work.”

Navigators help overcome language barriers

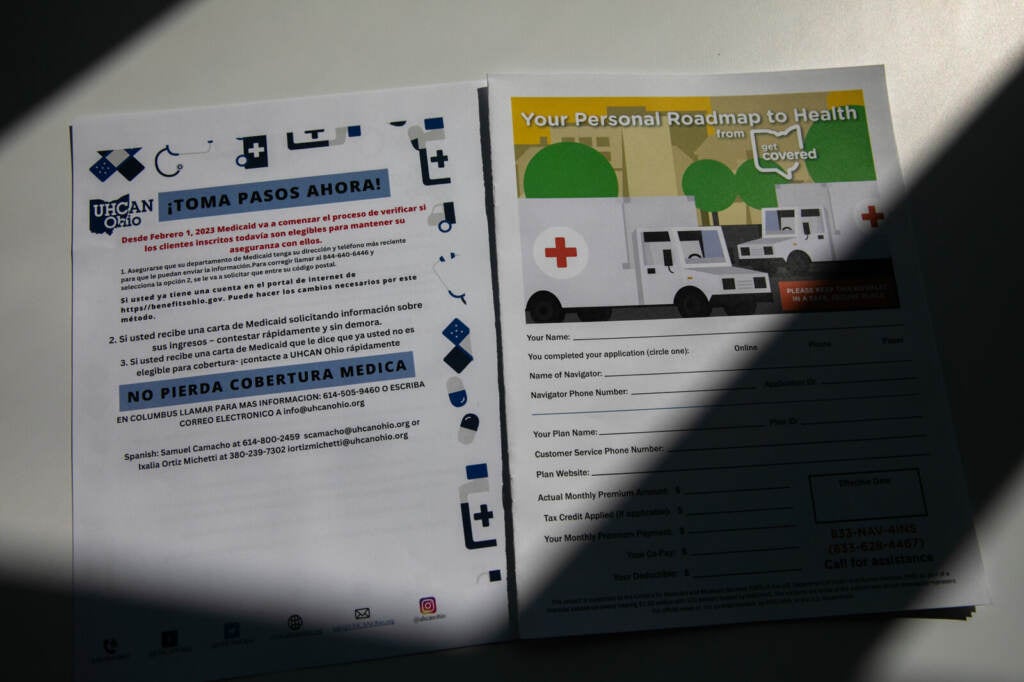

Samuel Camacho, a health insurance navigator with the Universal Health Care Action Network of Ohio, says language is another major barrier. “Individuals are going to be vulnerable because of their lack of English. So they may receive a letter, but they can’t read it,” he says. Navigators like Camacho guide people in signing up for Obamacare, but they can also assist them with Medicaid.

Camacho helps Spanish speakers in the Columbus, Ohio, region. He says the process has gotten much harder, because the local offices for the agency that handles Medicaid have been closed to the public since the pandemic.

“Before the pandemic, individuals were able to go to the offices with an interpreter and have conversations with their case managers, print documents, find documents in their language, have interactions with people, even other Medicaid recipients. We’ve lost that,” Camacho says.

He says that kind of word of mouth is really important for the Latino community he works with. “Latinos – we’re a group that thrives on communication. ‘Abuelita le dijo a Titi, Titi le dijo al primo y el primo me lo dijo a mi.’ [Grandma told auntie, auntie told the cousin, and the cousin told me.] So we’re losing that.”

Nowadays, Camacho helps Spanish speakers, often mothers, with Medicaid enrollment over the phone or at public libraries. He says the process generally takes two hours. But that’s just the start of it. He says he often has to interpret when the state sends requests for more documentation.

For example, he said, a person might submit a bill under their spouse’s name, but it needs to be under both their names. “Little details. And if those details are not taken care of, you’re denied,” he says.

Camacho says in his experience, those denials happen more often than not. And even though they’re usually overturned on appeal, “it’s the heartache of having to do it again and again and again. Makes no sense.”

As frustrating as it can be, Camacho says he wants to make sure everyone on Medicaid knows they will have to re-enroll in the coming months.

Adds Bamberger: “We try to spread the word that the most important thing is to update your current information and watch your mail.“

Dominique Jackson in Columbus already filed his Medicaid reenrollment paperwork.

Having Medicaid – and staying enrolled – has turned out to be life-saving for him. Eight months ago, Jackson was diagnosed with stomach cancer.

“I just went into remission for cancer last month,” he says. “Without the Medicaid, I don’t know how I would’ve been able to pay – it would have to completely have come out of pocket for the price of the medicines and treatments.”

He says this could be his last time relying on Medicaid. He’s hoping he’ll soon be hired at the trucking agency where he’s been temping and get on their insurance plan.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)