Is genocide predictable? Researchers say absolutely

In this file photo, Rohingya Muslims, who crossed over from Myanmar into Bangladesh, use a makeshift footbridge as they move with their belongings after their camp was inundated with rainwater near Balukhali refugee camp, Bangladesh, Tuesday, Sept. 19, 2017. (Dar Yasin/AP Photo)

History unfortunately does repeat itself.

Two thousand years ago the Romans laid siege to Carthage, killing more than half of the city’s residents and enslaving the rest.

Hitler attempted to annihilate the Jews in Europe. In 1994 the Hutus turned on the Tutsis in Rwanda. The Khmer Rouge killed a quarter of Cambodia’s population. After the breakup of Yugoslavia, Serbs slaughtered thousands of Bosnians at Srebrenica in July of 1995.

Last year when Buddhists attacked Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, many people were shocked to hear that mass killings still occur in the 21st century. But they do – and there’s growing evidence that these events follow familiar patterns. And if they do, we should be able to see them coming.

“Genocides are not spontaneous,” says Jill Savitt, acting director of the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. “In the lead-up to these types of crimes we do see a consistent set of things happening.”

Since 2014, the Holocaust Museum and scholars from Dartmouth have mapped the conditions that precede a genocide. They built a database of every mass killing since World War II. Then they went back and looked at the conditions in the countries where the killings occurred just prior to the attacks. And now they use that computer model to analyze which nations currently are at greatest risk.

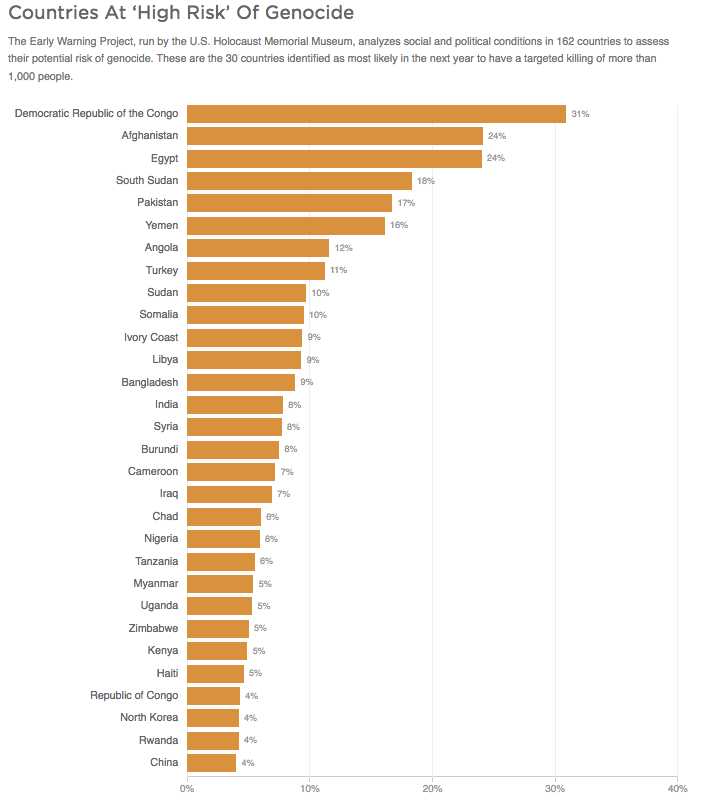

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

“We’re not forecasting with precision. That’s not the intention of the tool,” Savitt says. “What we’re doing is trying to alert policymakers that here’s a situation that is ripe for horrors to happen and give them a heads up that there are actions that can be taken to avert it.”

In the three years prior to the attacks on the Rohingya, Myanmar ranked as the country most likely to have a mass killing for two of those years and ranked No. 3 the other year.

The museum’s computer model analyzes statistics that you might think have nothing to do with genocide — fluctuations in per capita gross domestic product, infant mortality rates, overall population. Such factors, they believe, are indicators of inequality, poverty and economic instability.

They also plug in data about recent coup attempts, levels of authoritarianism, civil rights, political killings and ethnic polarization.

Lawrence Woocher, the research director at the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the U.S. Holocaust Museum, has worked on the Early Warning Project since 2014. He says that the form of government is one of the key data points in their computer model. The most dangerous appears to be a regime that’s not a full dictatorship but also not a full democracy.

“The prevailing view about why mass atrocities occur is that they tend to be decisions by political elites when they feel under threat and in a condition of instability,” Woocher says. “And there’s lots of analysis that suggests that these middle regime types are less stable than full democracies or full autocracies.”

The Early Warning Project ranks 162 countries by their potential for a new mass killing to erupt in the coming year. They define a “mass killing” as more than 1,000 people being killed by soldiers, a militia or some other armed group. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is currently the most at risk followed by Afghanistan.

Egypt is No. 3 on the list. The researchers note that Egypt was ranked so high because of a variety of factors including a lack of freedom of movement of men, a history of mass killings and a recent coup d’etat. They add that Egypt faces multiple security threats and that “there have been reports of large-scale attacks by extremist groups, including IS [Islamic State], on Christians and Sufi Muslims, and violence against civilians perpetrated by both insurgents and government forces in the Sinai Peninsula.”

War-torn South Sudan is No. 4 on the list. Its incredibly brutal civil war is expected to get even worse.

Greg Stanton, a professor at George Mason University and the president of Genocide Watch, agrees with the goal of the Early Warning Project rankings but disagrees with their methods. Stanton says the Holocaust Museum’s model is overly dependent on national data that’s often released only once a year.

“They tend to notice that there is a risk of genocide too late,” Stanton says.

Rather than looking at statistics to try to predict mass killings, he argues that you should look at events.

“In other words, it’s not enough to know that you have an authoritarian regime,” he says. “It’s important to know what that authoritarian regime is doing.”

Stanton has come up with a genocide prediction model based on 10 stages of genocide. His model starts with classification of people by ethnicity, race or religion, moves through dehumanization, persecution and extermination before stage 10 — denial during and immediately after a genocidal act.

Interestingly, the U.S. currently ticks off many of the early stages of a country headed for a bloodbath, according to Stanton. There’s polarization, discrimination, dehumanization. But strong legal and government institutions in the U.S. are likely to block such a disaster from happening, he says.

The information that Genocide Watch and the Holocaust Museum are sifting through has been available to national security agencies for decades. The big question is what to do with this information. At the time of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, Stanton was working in the State Department; he says top government officials knew that the violence was about to begin.

“When President Clinton said after the Rwandan genocide, ‘We really didn’t know.’ I’ll be direct. He was lying. He did know,” Stanton says. “I’ve read the confidential cables that came in from Rwanda from our ambassador there months before that genocide. And they knew it was coming.”

Stanton’s 10 stages of genocide and the Holocaust Museum’s Early Warning Project are both attempts to spread information more widely about the early rumblings of a genocide so that world leaders and others might be able to stop it.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))