In the quest for a liver transplant, patients are segregated by prior alcohol use

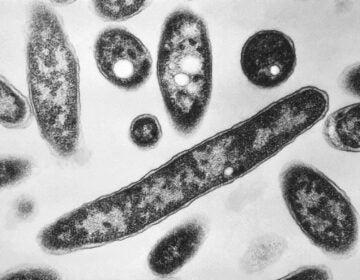

Surgeons remove the liver and kidneys of a deceased donor, for later transplantation. Owen Franken/Getty Images

The night before Brian Gorzney planned to check into rehab for alcohol use, he began vomiting blood. First at 2 a.m. Then 5. And again at 11.

When he arrived at the rehab facility in North Kansas City, Missouri, they sent him directly to the adjoining hospital. There, Gorzney, then 50, and his family learned he had severe alcoholic hepatitis, an inflammation of the liver typically associated with excessive alcohol use.

Gorzney had been drinking heavily on and off for years and, by February 2020, was having as many as a dozen drinks a day. His only chance of survival was a liver transplant, doctors said.

“So let’s do that,” his daughter Cameron Gorzney, now 22, told them. She was ready for anything that would save her dad, the man who had coached her softball team until high school, and later cheered from the stands at every game.

But Gorzney wasn’t eligible for a transplant, the doctors said. He hadn’t been six months sober.

A widely enforced waiting period, but is it justified?

In the U.S., a widespread clinical practice requires patients with alcoholic liver disease to complete a period of sobriety before they can get on the waiting list for a liver.

This informal policy, often called “the 6-month rule,” can be traced to the 1980s. The thinking then — and among proponents of the practice today — was that six months of abstinence gave a patient’s liver time to heal and, thus, avoid a transplant. If that didn’t work, the patient would at least have proven they can stay sober and would not return to drinking after a transplant.

However, a landmark European study published in 2011, as well as several American studies in the decade since, have exposed flaws in that premise. Six months of abstinence is not a good predictor of long-term sobriety, and for people with conditions like Gorzney’s, more than half die within that time.

Now, as the understanding of addiction evolves — to view it as a disease rather than a personal failing — many surgeons and families say the six-month wait unfairly penalizes those with substance use disorder. And with alcoholic liver disease rising among young adults and pandemic-related drinking exacerbating those numbers, it has become a pressing concern.

“We have to move beyond denying people lifesaving therapy because we think they don’t deserve it,” says Dr. Andrew Cameron, head of the liver transplant program at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. Doctors don’t withhold treatment from people with diabetes who are obese or people with sexually transmitted infections who had unprotected sex, he adds.

Cameron and his colleagues published a study this August, which examined patients with alcoholic liver disease who were made to wait six months and those who were not. The study found about 20% in each group returned to drinking one year after their transplants. That means about 80% stayed sober, regardless of how long they abstained from alcohol before the surgery.

The study did not include patients with liver diseases unrelated to alcohol, but Cameron says a similar proportion of those patients — who are not subject to the waiting period — follow the guidelines to stop drinking post-surgery. “There was nothing at all helpful or predictive about a six-month waiting period,” Cameron says.

Will patients care for the ‘gift of the donated organ’?

No national regulation determines how long a patient needs to be abstinent before being added to the waitlist; each transplant center sets its own policies. As of 2019, only about one-third of liver transplant hospitals in the U.S. had performed a transplant without the waiting period. Patients who don’t live near those centers — or don’t have the knowledge and resources to get there — can die without ever making it onto the waitlist, Cameron says.

A similar guideline is in place for patients with lung disease. Most transplant centers require them to stop using all nicotine products for six months before being added to the waitlist for a lung. But as research grows on addiction being a disease, some doctors are reevaluating that practice too, Cameron says.

On the other hand, some physicians worry abandoning the six-month rule could overwhelm the limited supply of donor organs. With nearly 12,000 people on the waiting list for a liver, it’s crucial to ensure patients who receive transplants are ready to care for themselves and the “gift of the donated organ,” says Dr. Kenneth Andreoni, a transplant surgeon and past president of the United Network for Organ Sharing, which manages the nation’s transplant system. (UNOS determines who ultimately receives a donor organ, but it does not determine who can or cannot be put on the waitlist.)

Since 2016, alcoholic liver disease has been the most commonly identified diagnosis among those waiting for a liver transplant, and since these patients often have dire prognoses with little time to live, they can quickly jump to the top of the waiting list, surpassing those with liver cancer or other diseases. When one patient receives a liver, “someone else is not getting that organ,” Andreoni says. “It’s just math.”

Andreoni says more long-term research is needed: “If all these people [who receive transplants without the waiting period] are doing great and living 15 years, then that’s the right answer.” Only time and statistics will tell, he believes.

Dr. Josh Levitsky, treasurer of the American Society of Transplantation, says some hospitals may worry that transplanting organs into patients with a higher risk of relapse could result in poor outcomes, threatening their accreditation or insurance contracts.

In addition, some insurance companies have similar restrictions, requiring patients to provide documentation of a sobriety period before agreeing to cover the cost of transplant surgery. A study examining Medicaid policies in 2017 found 24 states had such policies in place for their Medicaid recipients, while 14 did not. (Twelve states didn’t perform any liver transplants that year.)

In Brian Gorzney’s case, insurance wasn’t the issue. Finding a hospital to say yes was.

A race to find a transplant center willing to take a chance

When the team at North Kansas City Hospital, which is not a transplant center, suggested Gorzney look into hospice options, his family refused. They took him across state lines to the University of Kansas Health System for a second opinion.

There, Gorzney’s daughter Cameron, his ex-wife (Cameron’s mom), his then-girlfriend and his sister teamed up to explain why they knew Gorzney would stay sober and care for a new liver responsibly. He had held steady jobs throughout his life, they said. He had never had a DUI. He coached his daughters’ softball teams and was like a father figure to his sister, who is 10 years younger. He was headed to rehab before this crisis started, and he had a supportive family to help him sustain sobriety after surgery.

But, ultimately, the hospital’s transplant committee said no.

In a statement about the general transplant process, Dr. Ryan Taylor, medical director of liver transplantation at the hospital, said each candidate is reviewed by a committee of more than 30 members. “High-risk transplant patients may be required to complete 6 months of counseling to demonstrate an ongoing commitment to sobriety,” he wrote, but there is an “expedited pathway” for people with alcoholic hepatitis who also have a “low risk for recidivism.”

Gorzney was considered for this pathway, but the committee didn’t approve him, his daughter Cameron says.

She was devastated by the no. But she’s stubborn, she says, just like her dad. So, she and the rest of the family frantically scoured news articles and academic studies and called transplant hospitals across the country for another option.

“My dad was really deteriorating each day,” she says.

They finally settled on the University of Iowa, where Cameron Gorzney had attended her first year of college and heard of its renowned medical system. The family made their case on Gorzney’s behalf again. This time, they got a yes. The family’s group text exploded, Cameron recalls.

Dr. Alan Gunderson, medical director of liver transplantation at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, says most hospitals that allow transplants without the six-month wait look at similar factors: the patient’s medical need, financial stability, social support, understanding of their addiction and desire to recover. But the subjectivity of these measures means different transplant committees can come to different decisions.

In a letter to Gorzney, the Iowa transplant team explained they’d typically recommend a six-month waiting period but were approving him for the waiting list immediately because he wouldn’t survive otherwise. In return, Gorzney agreed to attend counseling and treatment programs after the transplant.

Within 24 hours of being put on the waitlist, Gorzney received a new liver.

Today, more than a year and a half later, Gorzney, 52, is still sober and embracing the “opportunity to be somebody that I haven’t been in a while,” he says.

He and his girlfriend are engaged, and he’s grateful to see his daughters, Cameron and Carson, grow into young adults. A lifelong Illinois Fighting Illini football fan, he even considers rooting for the Iowa Hawkeyes now.

But it worries him that the six-month rule, which led his family to travel to three hospitals in three states, still stymies others.

“People are, unfortunately, passing away…not knowing that there may be other options for them because they don’t have a support group that I had that was aggressive enough and strong enough to reach out and not accept no on the first response they got,” Gorzney says.

This story was produced in partnership with KHN (Kaiser Health News), a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))