In 1968, poor Americans came to D.C. to protest, some by mule

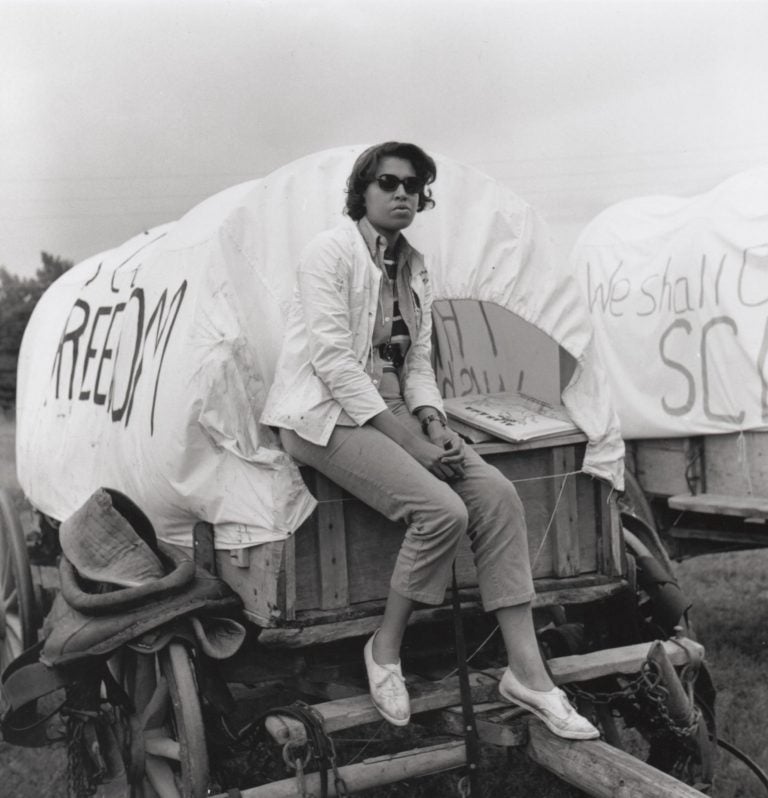

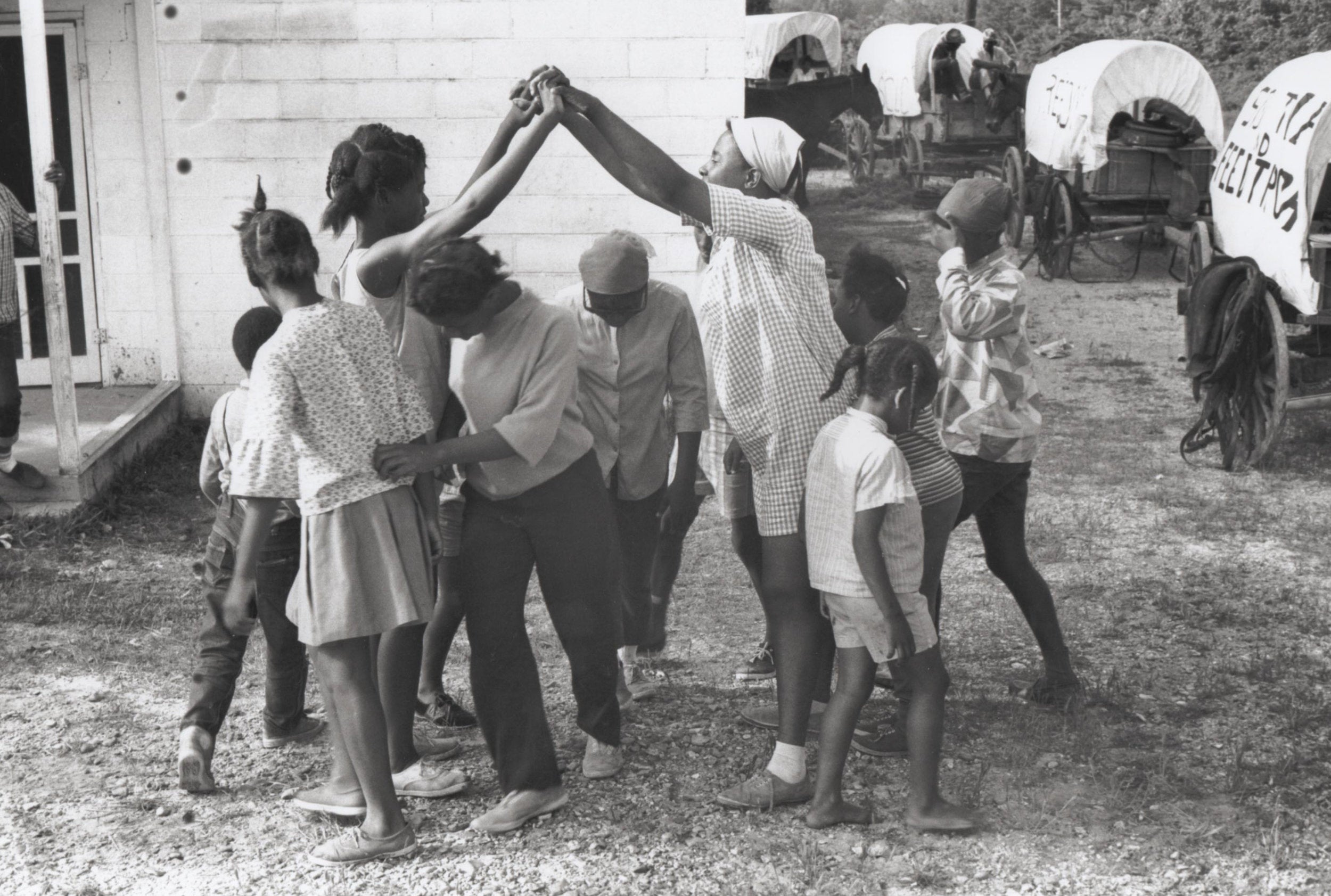

Joan Cashin volunteered to help organize and prepare the Mule Train. (Courtesy of Roland Freeman)

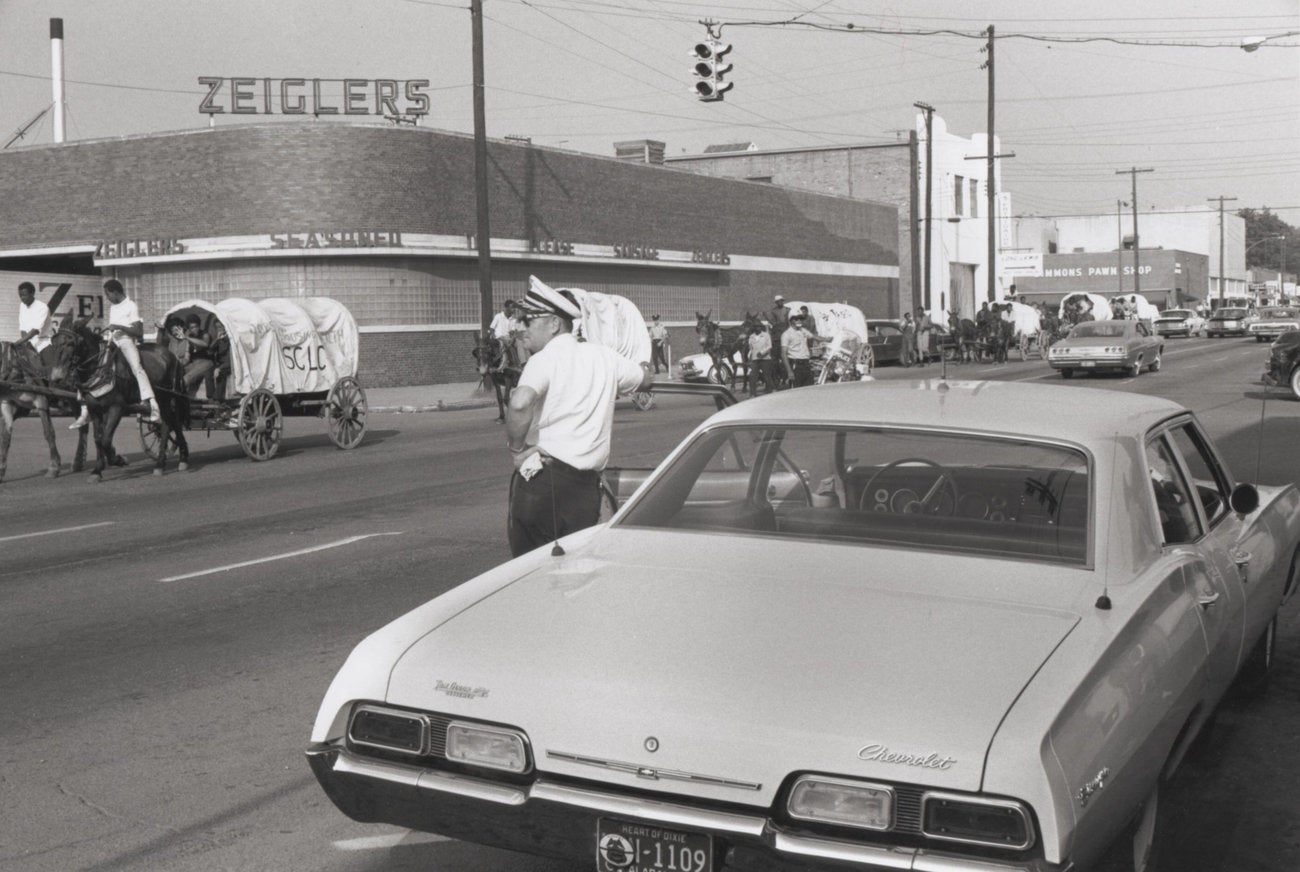

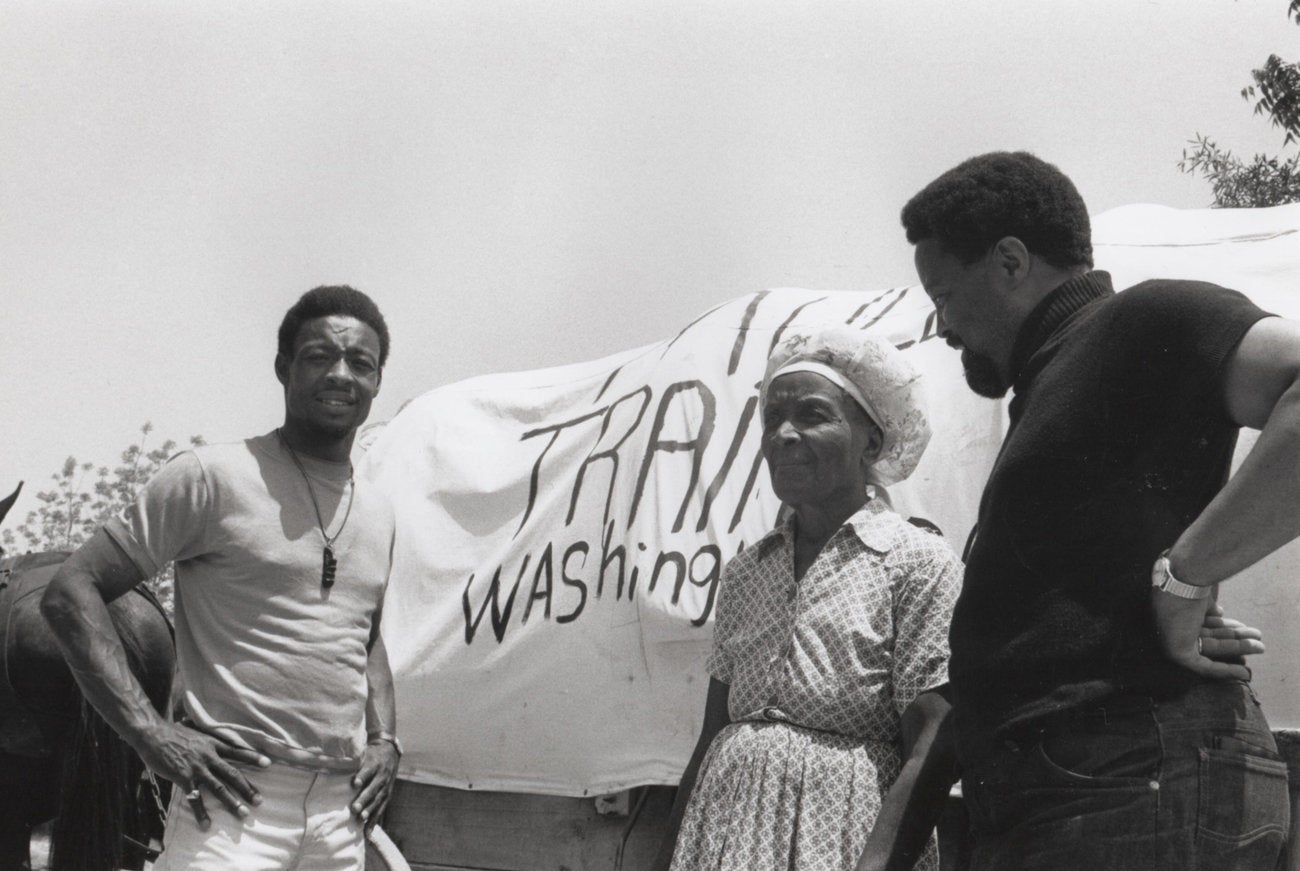

Fifty years ago, photographer and folklorist Roland Freeman hitched his hopes to a humble caravan of mule-driven wagons. The Mule Train left the small town of Marks, in the Mississippi Delta, for Washington, D.C. It was part of Martin Luther King Jr.’s last major effort to mobilize impoverished Americans of different races and ethnic backgrounds.

“We’re coming to Washington in a ‘Poor People’s Campaign,’ ” King said on March 31, 1968, only days before he was assassinated. One of the most symbolic groups making the journey to demonstrate at the National Cathedral was the Mule Train. When King visited Marks, he said he saw “hundreds of black boys and black girls walking the streets with no shoes to wear.”

Freeman offered to cover the trip for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the civil rights group King led until his death. King’s rousing “I Have a Dream” speech had inspired Freeman to join the civil rights movement as a photographer, and he started documenting African-American life the way he saw it.

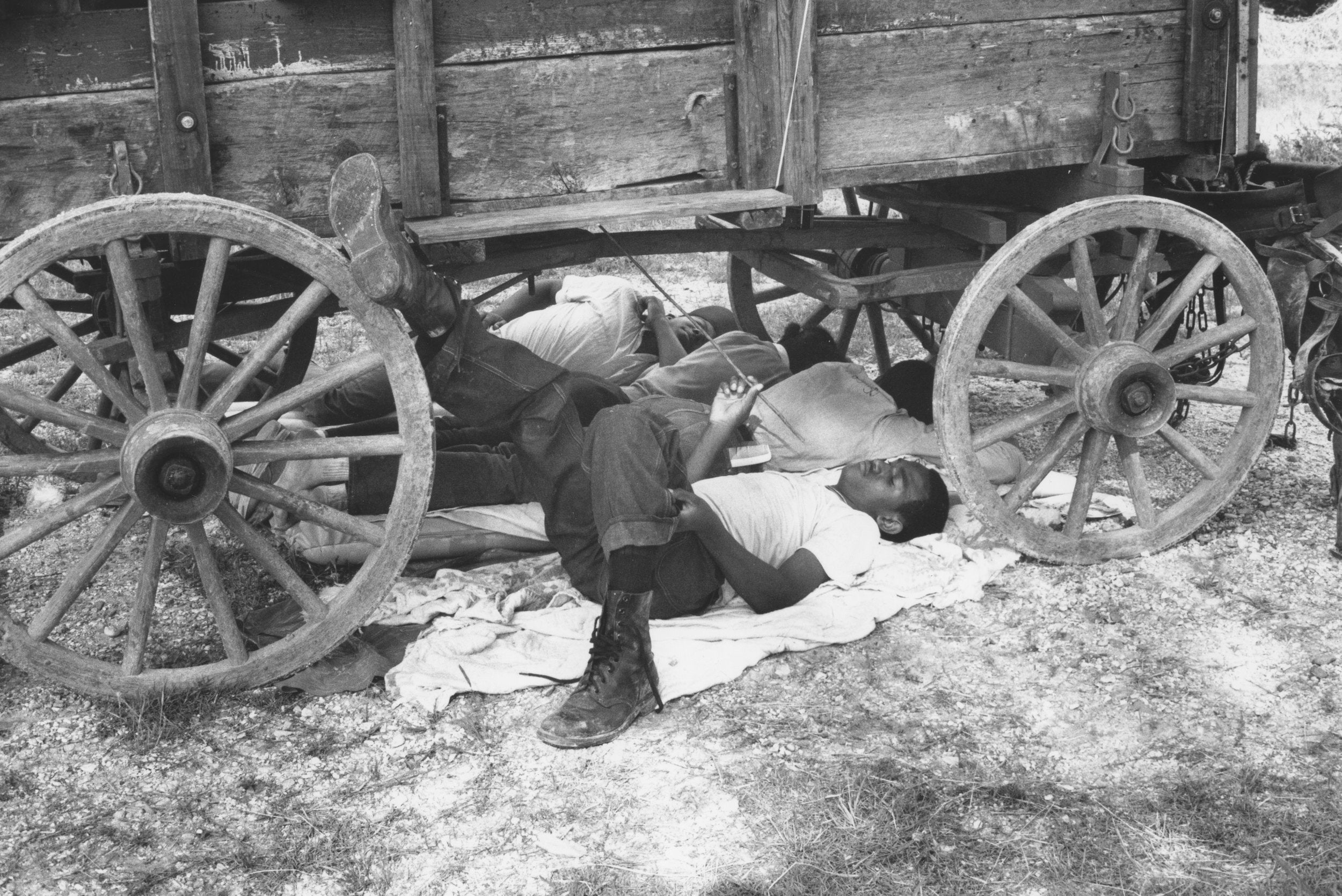

During the trip, Freeman rode in different wagons, recording interviews and taking pictures. He never had formal training in photography. Instead, he studied Depression-era photographs in the basement of the Library of Congress, which was five blocks from his home.

He said he “looked up everything that Gordon Parks had ever done for Life.” Parks, the first African-American to work as a staff photographer for Life magazine, later became a mentor.

Every photographic decision was by feel, by trial and error. Though Freeman said he wishes he had been a more experienced photographer at the time, his work has since been published widely and exhibited throughout the U.S., Europe and Africa. One of his books, The Mule Train: A Journey of Hope Remembered, came out in 1998 to commemorate the 30th anniversary.

The photographs reconciled the moments of the journey with histories and reflections from those who traveled in the caravan.

One story has always stuck with Freeman. Lydia McKinnon, a schoolteacher who volunteered in planning the Mule Train, was attacked.

“She had this big scar on her face, and I said, ‘My God, Sister, what happened to you?’ ” Freeman recalled.

McKinnon explained later that sheriff’s deputies and state troopers had beaten her and other demonstrators who refused to disperse after the arrest of Willie Bolden, a field office worker with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and wagon master for the Mule Train.

“She felt the heels of their boots and the butts of their guns, as she laid on the ground,” Freeman said. “And all I could think of was, if they would do that to her, what will they do to me?”

He took her portrait. Her young, pleasant face, framed by a gauzy scarf and permed hair, is marred by welts and bruises on her forehead and cheeks.”My life flashed before me,” McKinnon recalled in Freeman’s book. “I had been in the segregated South all my life. White folks had the best of everything and what we blacks had was less than second best. So for that one crazy moment I stood up for what was right.”

The Mule Train ran a dangerous route. Many locals didn’t want it coming through their towns. But looking back, Freeman admires the participants’ courage for making the trip and the residents, many African-American themselves, who offered help along the way.

“They would say, ‘You can stay on my land. You can put your mules over here. You can bed down here,’ ” he said. “Folks that didn’t have hardly nothing. Sharing everything they had with you, I mean, ‘Y’all come on in. I’m cooking some cornbread. I’m making a pot of beans.'”

The memories of kindness made Freeman choke up.

“They gave you what they had, from the heart. They’d wish you well from the heart,” he said. “That’s when I really realized, there was no place else on Earth I’d rather be than right there, experiencing that.”

In audio recordings he shared exclusively with NPR, organizers like Andrew Young are heard discussing caravan logistics, such as budgeting and scheduling rest stops.

Freeman likened the Mule Train trip to an old Western movie — families made their way out to a new land in covered wagons, for the promise of new lives.

Looking back on the Mule Train, he believes the risks were worthwhile. “I’m glad it took place, and I’m glad I’m a part of it,” he said. “The people who participated in it had a wonderful experience.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))