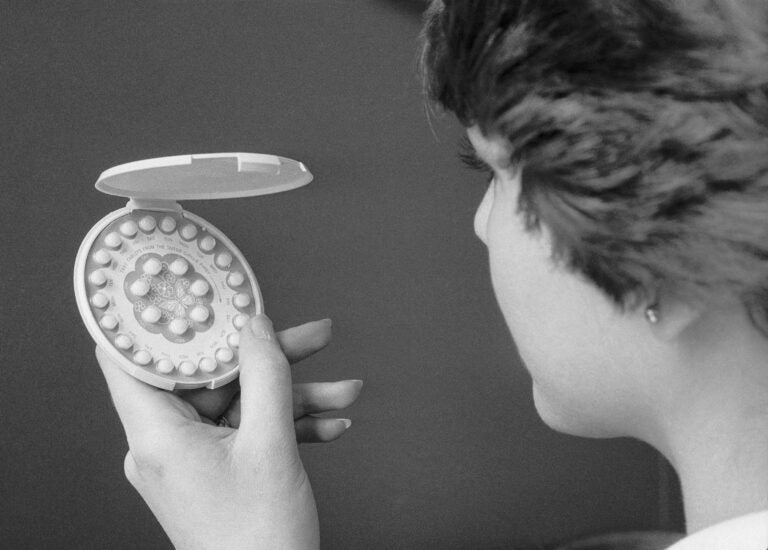

How the approval of the birth control pill 60 years ago helped change lives

Birth control pills in 1976 in New York. The birth control pill was approved by the FDA 60 years ago this week. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Updated at 9:44 a.m. ET

As a young woman growing up in a poor farming community in Virginia in the 1940 and ’50s, with little information about sex or contraception, sexuality was a frightening thing for Carole Cato and her female friends.

“We lived in constant fear, I mean all of us,” she said. “It was like a tightrope. always wondering, is this going to be the time [I get pregnant]?”

Cato, 78, now lives in Columbia, S.C. She grew up in the years before the birth control pill was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, on May 9, 1960. She said teenage girls in her community were told very little about how their bodies worked.

“I was very fortunate; I did not get pregnant, but a lot of my friends did. And of course, they just got married and went into their little farmhouses,” she said. “But I just felt I just had to get out.”

At 23, Cato married a widower who already had seven children. They decided seven was enough.

By that time, Cato said, the pill allowed the couple to avoid having more babies — and she eventually was able to go on to college.

“It was just like going from night to day, as far as the freedom of it,” Cato said. “And to know that I had control, that I had choice, that I controlled my body. It gave me a whole new lease on life.”

Loretta Ross, an activist and visiting women’s studies professor at Smith College, was among the first generation of young women to have access to the birth control pill throughout their reproductive years.

Ross, now 66, said by the time she came of age around 1970, the pill was giving young women more control over their fertility than previous generations had enjoyed.

“We could talk about having sex – not without consequences, because there were still STDS … but at the same time, with more freedom than our foremothers had,” Ross said. “So it changed the world.”

For all it’s done for women, Ross said that the pill has a complex and controversial history; it was first tested on low-income women in Puerto Rico. Ross said the pill also has limitations; she’d like to see it made available over the counter, as it is in some countries – not to mention, a pill for men.

When the pill was approved in 1960, women had few relatively few contraceptive options, and the pill offered more reliability and convenience than methods like condoms or diaphragms, said Dr. Eve Espey, chair of the Department of Ob/Gyn and Family Planning at the University of New Mexico.

“There was a huge, pent-up desire for a truly effective form of contraception, which had been lacking up to that point,” Espey said.

By 1965, she said, 40% of young married women were on the pill.

For Pat Fishback, now 80 and living in Richmond, Va., the newly-available pill allowed her to delay having children in her early 20s until she’d been married for a couple of years.

“It also made having children a positive experience,” Fishback said. “Because we had actually, emotionally and intellectually, gotten to the point where we really desired to have children.”

It took a bit longer for unmarried women to gain widespread access to the pill and other forms of contraception: Linda Gordon, 80, a historian at New York University, remembers the stigma around single women and contraception at the time.

“When I was in college, a number of women had a wedding ring – a gold ring –that we would pass around and use when we wanted to go see a doctor to get fitted for a diaphragm,” Gordon said. “In other words, there were people finding their way to do that, even then.”

The pill also gave rise to a variety of other forms of hormonal contraception, many of which are popular today, Gordon said. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 13% of American women of reproductive age use the pill — making it the second most popular form of contraception, after female sterilization.

Gordon said that 60 years after the pill’s approval, contraception remains a contentious political issue.

Just this week, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in a case involving the birth control mandate in the Affordable Care Act. A decision on whether some institutions with religious or moral objections can deny contraceptive coverage to their employees is expected in the months to come.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))