Coal jobs have gone up under Trump, but not because of his policies

President Trump praised the 2017 opening of this mine in Friedens, Pa., which created around 100 jobs. (Dake Kang/AP)

President Trump made coal jobs a core of his presidential campaign, repeatedly vowing to bring back “beautiful” coal despite the industry’s decades-long decline. And in pockets of the U.S. during Trump’s first year in office, it may well have felt like a turnaround was underway.

A review of data from the Mine Safety and Health Administration shows 1,001 more U.S. coal jobs last year compared with 2016, although energy analysts say the reasons are short term and have nothing to do with White House policies.

The biggest jump was in West Virginia, where MSHA’s annual average found 1,429 more coal jobs in 2017. One U.S. congressman from West Virginia, David McKinley, the chairman of the Congressional Coal Caucus, was quick to declare that “Trump has ended the war on coal” — one he said had been created by President Barack Obama.

Other states that saw a sizable increase: Alabama (494), Virginia (243) and Pennsylvania (124). Seven other states saw a smaller number of new coal jobs.

Other states that saw a sizable increase: Alabama (494), Virginia (243) and Pennsylvania (124). Seven other states saw a smaller number of new coal jobs.

“I think Trump should be patted on the back because we need this coal,” retired Virginia miner Noah Counts tells NPR.

Energy Economist Rob Godby, at the University of Wyoming, calculates MSHA data differently, comparing fourth-quarter 2016 and 2017 numbers. By that measure he also finds a 2 percent bump in coal employment in Wyoming. But that was alongside a 6 percent rebound in production, which means mines are doing “more with fewer people.” Godby thinks that reluctance to hire more workers, perhaps relying on overtime instead, means mine owners are “uncertain about future production.”

Energy Economist Rob Godby, at the University of Wyoming, calculates MSHA data differently, comparing fourth-quarter 2016 and 2017 numbers. By that measure he also finds a 2 percent bump in coal employment in Wyoming. But that was alongside a 6 percent rebound in production, which means mines are doing “more with fewer people.” Godby thinks that reluctance to hire more workers, perhaps relying on overtime instead, means mine owners are “uncertain about future production.”

Short-term jobs bump, long-term decline

The Trump administration has certainly tried to help the coal industry, rolling back a number of environmental regulations, imposing tariffs on imported solar panels, and proposing to subsidize both coal and nuclear (a move regulators rejected). But Godby and other analysts credit last year’s rise in coal jobs to short-term market forces, here and overseas, including a powerful cyclone that battered Australia.

Australia is the world’s leading producer of metallurgical coal, a special kind used in steelmaking. But last March, Tropical Cyclone Debbie disrupted that market. Art Sullivan, a mining consultant and former coal miner in Washington, Pa., told NPR last year that this disruption, along with “a continuing high level of demand in China,” boosted demand for exports of “met” coal in places such as Appalachia and Alabama. That’s why Trump could tout “a big opening of a brand-new mine” in Pennsylvania when he announced the U.S. would leave the Paris climate accord last June.

Met coal is the smaller, but more profitable share of the U.S. industry. By far, most American coal is thermal, or steam, the kind used to make electricity. For years, low-cost competition from natural gas has forced such plants to shut down, or switch from coal to gas. Thermal coal got a bit of a break in 2016, as natural gas prices rose from very low levels in 2016. But it still continued its long-term decline.

“Natural gas is more flexible; it’s cheaper to operate and it’s also more efficient,” David Sorrick, senior vice president for power operations with the Tennessee Valley Authority, tells Ohio Valley Resource. TVA’s Paradise power plant in Kentucky, for example, retired two of its three coal-burning generators last year in favor of natural gas.

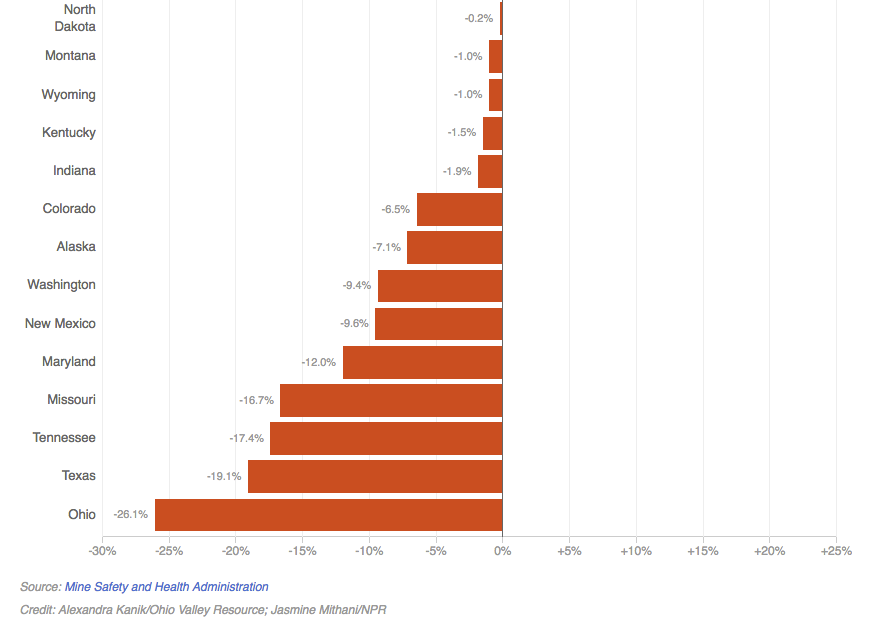

According to MSHA’s annual averages, Kentucky lost 108 coal jobs last year. Two states had bigger losses, Texas (503) and Ohio (401). Five other states lost several dozen coal jobs, including Wyoming (again, by a different calculation than economist Godby uses).

Godby says strong global growth may keep the metallurgical coal market a “bright spot” for a while longer. But he notes those exports are just a fraction of what they were years ago and says they won’t change coal’s overall downward trend. The number of U.S. coal miners has plunged from 90,000 in 2012 to just over 50,000 today, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And in fact, in the last quarter of 2017, production and jobs were back down.

Many mines will continue to automate, Godby says, cutting jobs to cut costs, and hold on as long as they can. There will be more pressure as wind and solar electricity becomes even cheaper, and electricity demand stays flat.

Based on retirements already announced, analysts expect a jump in the number of mines that could close in 2018. Just last month, the 4 West Mine in southwestern Pennsylvania announced it will shut down, meaning jobs will disappear for about 400 workers. That’s far more than the number of new coal jobs in the state last year.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))