West Philly Pastor Empowers At Risk Youth, Providing Fun, Food and Healing

Pastor Aaron Campbell meets kids where they are and helps them “level up” to their full potential.

Listen 5:04

Aaron Campbell, pastor of Antioch Christian Fellowship Church and founder of Level Up, standing in the program’s garden. Photo by Cherri Gregg

“We are an interventional grassroots youth mentoring program,” says Aaron Campbell. “We intervene in a time of crisis- but we don’t just serve young people, we empower them as well.”

Campbell is pastor of Antioch Christian Fellowship Church located near 47th and Chestnut Streets in West Philadelphia. He’s also founder of Level Up, a program that supports youth ages 10 to 25 who are most at risk of gun violence.

Campbell runs the program out of his 12,000 square foot church, which is complete with an arcade, four 80-inch flat screen TV’s with videogame consoles, an industrial kitchen and a church sanctuary. There are also quiet rooms for studying, tutoring and counseling and so much more.

“This is an oasis in the middle of the concrete jungle,” says Campbell.

Outside the church, there is a lush, 2500 square foot vegetable and herb garden, as well as greenspace for young people to play and hang out. And, on any given Tuesday, nearly 200 kids flock to Level Up and on Thursday, that number hovers around 600.

“They come from everywhere,” says Campbell, “Southwest Philly, Kensington and Allegheny, North Philly. They will commute for 90 minutes to 2 hours to get here—some even come from Camden.”

The young people come for a variety of reasons, but food is a big part.

“We have some that show up on a Thursday and I ask them, ‘when’s the last time you ate,’” says Campbell, “and they will tell me ‘on Tuesday’ when I fed them.”

On one Thursday afternoon this past summer, Campbell cooked 80 pounds of curry chicken, grilled 250 burgers, fried hundreds of mozzarella sticks, baked chicken wings, and prepared more than two dozen filets of teriyaki salmon. Volunteers also served five flavors of water ice. Campbell says the church spends about $4500 a week on food, sometimes more, thanks to donations and sponsors. But the cost is worth it.

“We give them choices and tell them they can eat whatever they want,” he says, “we are giving them power.”

Campbell says many of the young people rely on the meals served at Level Up. The kitchen has a stocked pantry that they call the “Poppy Store.” There, young people have access to unlimited noodles, cereal, milk and snacks and are encouraged to take food home and share it with their siblings.

“People don’t understand what real poverty looks like,” says Campbell, “it’s real and it’s 24/7.”

Philadelphia is the poorest large city in America, with one in three kids in the city living below the poverty line. It’s a statistic and a reality that Campbell says most people are unaware of. He says the city’s young people are forced to deal with issues ranging from hunger, to housing to safety. Level Up tries to empower kids, by giving them more ways they can help themselves. For example, kids can wash their clothes at Level Up and get free haircuts.

“So many of these kids feel helpless,” he says, “the system has failed them, schools have failed them and no one cares. There’s a lot of anger and resentment—we want kids to know that they have value.”

A Weekly Dance Party.

Every Thursday, Campbell transforms his church sanctuary into a dance floor. A DJ will spin tunes and hundreds of kids, mostly young men, will battle on the dance floor. It’s hot, it’s sweaty and the young people are having a ball.

“They are the ones who actually are leading the culture in the Philly dance culture,” says Campbell, “we draw all the best dancers and of course, all the crowds who want to see the best dancers.”

“ You’re never quite prepared to walk into a Level Up,” says Stephanie Humphrey a member of Antioch Christian Fellowship Church. “Everything, everywhere, all at once is happening in this space.”

Humphrey nominated Campbell and his program for the Good Souls Project.

“They have truly created this space where all are welcome,” she says, “there are Muslim young people there, there are children of all faiths or no faith and Pastor Aaron is at the center of it all—he literally has a connection to every single student.”

A Father Figure

In his 40s, Campbell is a father to his own children, but the youth who come to Level Up call him “uncle, dad, daddy and godfather.” In their eyes he’s their parent too.

“He is a father figure to me and I’m more than a son figure to him,” says Akee Chambers, 24.

Chambers began coming to Level Up the program when he was 22. At the time, he had a gun felony on his record and had a hard time getting a job. Campbell connected Chambers to a Level Up sponsor. They hired him. Akee says Level Up Life changed his life.

“It’s the most impactful thing like that I’ve associated myself with and within the past ten years, honestly,” he says.

“We are changing statistics and changing the game,” says Campbell, who shared that Chambers’ job is with a major beverage company and pays more than 65,000 a year. “I am so proud of [Akee].”

Through Level Up, Campbell and his team have helped kids get into GED programs, job training and job opportunities.

“We’re reforming shooters, we’re reforming drug dealers, we have car thieves who we’ve reformed,” he says, “we meet kids where they are and then help them level up.”

Living a Double Life.

Campbell wasn’t always a pastor or role model. He was raised by a single mom, and grew up Newark, New Jersey in a rough neighborhood. Campbell’s mom and dad worked together to send both their children to private school. While Aaron excelled, he was attracted to the whispers of street life.

“The hip hop culture is all about money, power and respect on the streets,” says Campbell, “and you can have all of these accomplishments, but if you don’t feel like you have that cred on the streets then you feel like you’re not a real man.”

Campbell says that even after he got accepted into University of Pennsylvania, he his spent his summers and breaks working in a grimy section of Hells’ Kitchen. He says he used the time to earn credibility in the criminal world.

“I was living this Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde life,” he recalls, “I was just out of control. I should be dead or in jail.”

Once a self-described atheist, Campbell says he found God at age 22. He then made Philly his home for good. He says he began working with young people and eventually founded his own Church. Campbell has also worked as a police chaplain, international first responder and more. Level Up was born out of Campbell’s youth mentorship work, but he says the program became an official 501C3 five years ago.

Impact of Gun Violence.

“It’s been, like, family here forever,” says Chris, 21. “Everybody here is family.”

Chris has been coming to Level Up for a decade. He says it is a safe space where kids can let go of street beefs.

“That’s what we need,” says Chris, “because there’s a lot of violence and stuff going on. Actually, my friend just died yesterday.”

Chris pulled out his phone to show a photo of his lost friend. Campbell knew him as well.

“It’s taxing,” says Campbell. “I’ve had 16 kids in my program shot in the last 16 months.”

He says three were murdered in the past six months. Campbell held one of the funerals at his church.

“To see my own babies having to carry one of my babies out in the coffin– it kills me,” he says.

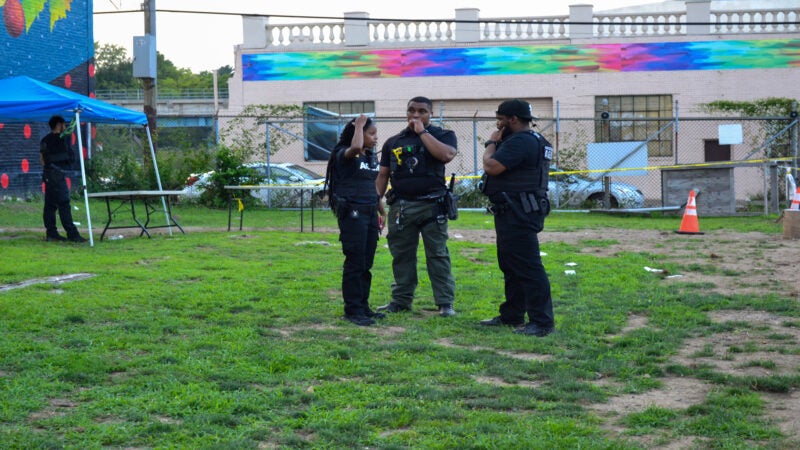

To ensure Level Up remains a safe space, Aaron secures the gatherings with the help of a team of heavily armed guards. Every kid who enters Level Up must walk through a metal detector and could be searched.

“If I walked you over there right now, you would see a box of tasers,” notes Campbell, pointing to a bin of items confiscated by the security guards.” “You’d see a box of combs that turn into knives, brushes that turn in the knives, large blades, mace, you name it. Guns? Well, they don’t even try because they know we’ll take them.”

Campbell says his team keeps their eye on the crowds of kids as they dance, eat and mingle. He says the guards know the kids well and if there is a fight, those involved are forced to leave, but the gathering will continue. Campbell says those who are removed could come back another day if they can resolve their issue. He says he believes in second, third and sometimes forth chances.

“I understand their anger,” he says, “kids can tell when people don’t care about them- we try to show them they matter.”

“When I hear the term “good soul,” I think of somebody who serves without expecting anything in return,” says Humphrey, “and I definitely think that that Pastor Aaron fits that bill.”

“It fills me with gratitude, hits me with humility,” says Campbell on being highlighted as part of The Good Souls Project, “It encourages me to want to really reach that bar.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.