The Big Chill and the Future of Refrigeration

Amid the summer heat, we explore the history and future of cold technology, from innovations in freezing to the next generation of air conditioners.

Frozen fish in a commercial freezer. Different river fish, fish cakes, sea bass.

We’ve only been able to harness the cold for our benefit for a little over 100 years, but innovations like refrigeration and air conditioning have completely transformed the way we live and eat.

A massive cold chain makes it possible to buy salmon from Alaska, grapes from Chile, and cheese from Italy; to have sushi in Kansas and ice cream in the summer. Air conditioning allows us to function and to be comfortable during the hot summer months. But it all comes at a cost, and not just financially. Refrigeration and air conditioning use a lot of energy, and that’s a problem in our ever-warming world.

On this episode, we look at how advances in cold technology have shaped our lives and changed the world — for better and for worse. We hear about working in a cold storage warehouse and the smell of frozen pizzas; about super-cold “blast” freezers that can bring us fresher seafood and reduce waste; and about the race to develop more sustainable air conditioners. We’ll also find out what it actually looks like to have your body cryonically preserved.

Also heard on this week’s episode:

- We talk with science journalist Nicola Twilley about the history of refrigeration, how it transformed the way we eat — and why it now poses a threat to our warming world. Her new book is called, “Frostbite: How Refrigeration Changed Our Food, Our Planet, and Ourselves.” Twilley is the co-host of the podcast Gastropod.

- It sounds like something straight out of a sci-fi flick — freezing your body after death in the hopes of one day living again. But in Scottsdale, Arizona, a nonprofit called Alcor has spent decades trying to make the cryonic preservation of humans (and a few pets) a reality. We talk with photographer Alastair Wiper about his visit to Alcor, and what he saw during his peek behind the curtain.

-

Read the transcript for this episode

MAIKEN SCOTT: This is The Pulse – stories about the people and places at the heart of health and science, I’m Maiken Scott.

I was at the grocery store last night, getting some food for the week, starting with veggies and fruit because they are right near the entrance…

MS: Cucumbers, I feel like I have too many already but oh well – can’t hurt, right? The lettuce looks kind of tired, – ooh they got cherries – cherries are expensive, though…

MS: I needed eggs, so I headed over to the dairy section with rows of refrigerators…

MS: I’m reaching into this fridge to get eggs, and I can see this whole huge space back here… that is essentially a gigantic refrigerator. I can see eggs, and a lot of milk, a ton of produce. Can you hear the fans running in the back?

MUSIC

MS: These big cold spaces in grocery stores are just one part of a massive cold chain that is crucial to our food supply. Just how crucial, was showcased by an experiment that happened about 15 years ago.

NICOLA TWILLEY: This is a really fun story… an activist called Waldo Jakewith. He had moved to this off-grid rural home in Virginia and started raising chickens and planting a vegetable garden.

MS: That’s science journalist Nicola Twilley. She says Waldo wanted to live off the land – and one day he had a great idea…he would make a cheeseburger from scratch – every part of it… step by step.

NT: Bake the buns, mince beef, harvest lettuce, you know, tomatoes, onions, you got to make cheese. And then he was like, wait, wait, wait, if I’m going to do this, I’m going to do it properly.

MS: Waldo realized he would have to start with all raw materials — plant and harvest wheat for the hamburger buns, grow mustard seeds to make the popular condiment.

And of course, he would have to raise at least two cows. One for the meat and the other for milk to make the cheese.

NT: He’s getting really excited. He’s got a long list. His to-do list is getting longer and longer. And then he starts scheduling it out. And that is when the whole project falls apart because it turns out that, you know, tomatoes are in season in the late summer. His lettuce, that’s only ready to harvest in spring and fall. Then you traditionally would slaughter a cow in November. That’s the slaughtering month once it’s cool enough, right, pre-refrigeration to not go bad. And the scheduling just does not add up. You cannot make all the components of a cheeseburger come together at the same time without a refrigerated food system. And then he realized, oh right, the cheeseburger was invented after the dawn of refrigeration, the 1920s, which is when refrigeration sort of became widespread in American homes.

MS: Nicola writes about this in her new book, “Frostbite: How Refrigeration Changed Our Food, Our Planet, and Ourselves”. She traces how refrigeration has become an integral part of our food system.

NT: Nearly three-quarters of everything Americans eat passes through this cold chain at some point on its journey from farm to fork. And it includes refrigerated shipping containers, refrigerated trucks, refrigerated ships, refrigerated train cars, refrigerated warehouses, of course.

MS: Cold temperatures keep rot and harmful bacteria at bay – the cold makes it possible for us to eat a great variety of foods no matter what season it is – but, there are downsides…

NT: No one has really added up all the costs and benefits. And it really matters, because there are costs as well as benefits.

MUSIC

MS: Refrigeration has allowed us to harness the cold for our ultimate benefit, not just with food. Lowering the temperature makes our homes, offices, and cars comfortable during the hot summer months. But the system is an energy-hungry beast that will need some upgrades to be sustainable…

On this episode: The big chill – how the cold shapes our food supply and our lives

MUSIC

MS: Let’s stick with science journalist, Nicola Twilley and her new book, “Frostbite”.

Her research for this book started at a cold storage warehouse.

NT: When I started exploring refrigeration, I realized that to really understand it, I needed to spend time in the cold, and go work in a refrigerated warehouse.

MS: This one was owned by Americold – a big company that runs lots of these places… Think of massive buildings with endless rows of chilled food — from apples to yogurt, to frozen pizza. This is essentially where our food goes before it hits the road to the grocery store.

MS: So what was it like when you entered this new, cold world?

NT: Well, this is going to sound really stupid, but it was cold!

MS: How cold? It was so cold. It was so, so cold. You think you know cold? I mean, admittedly, I live in Los Angeles, but I’ve lived in New York, I’ve lived in Chicago, I’ve traveled to Greenland. I know cold. But I think there’s something about working in the cold for hours on end, it just gets into your bones. And the funny thing is, this is a well-known phenomenon. Cold just, the reason it preserves our food is that it slows everything down, the process of respiration and decomposition, but it does that to the people who work there too. You just slow down.

Medical researchers who study this call it the ‘umbles’. You start to stumble, grumble, fumble, and mumble. And it’s true, you just sort of start shutting down. It also is a very weird, sort of dark, dense-feeling environment. Sound travels more slowly in cold air. And then the other thing that’s really interesting is odor. So, until you have worked in a frozen food warehouse and smelled the frozen pizzas, you have no idea what odor is all about. The smell of frozen pepperoni pizza lingered on my jacket collar for months.

MS: And that’s interesting because if I think about a frozen pizza box, I can’t even imagine like any smell coming out of that.

NT: Well, that’s one of the things that’s so interesting about going into a refrigerated warehouse is because when you go to the store, you might see, I don’t know, you know, an aisle full of frozen pizzas. There’s a lot, but it’s manageable. It’s more than you would ever eat, but it’s within the realm of possibility. When you go into a frozen food warehouse, you are looking at more frozen pizzas than you can imagine eating in several lifetimes. I mean they are, it’s just, you get this real sense of the scale at which America eats, what it takes to feed us all. And so I think it’s not one pepperoni pizza has a certain smell, but when you have thousands and thousands and thousands of pepperoni pizzas, it’s intense.

MS: Nicola says the conditions in these freezing-cold warehouses are a lot more nuanced and intricate than our refrigerators at home.

NT: When I look at my fridge, I see a one-size-fits-all solution, right? I mean, maybe you put the produce in the crisper drawer rather than like on the shelf, but it’s not, it’s not a big deal. You could put it in the, on the shelves in the door, you could put the chicken at the top, you could put it at the bottom. It doesn’t matter. Actually, in the sort of much more complex world of the cold chain where everything is being done to optimize the shelf life of these foods and extend their life a little bit longer.

So stone fruit can’t be at a certain temperature, but then bananas have to be at a particular temperature until they’ve been ripened in which case they can’t go below another temperature. Different fruits and vegetables even have their own preferred blend of gases. So it’s not just temperature. It’s humidity levels. It’s the amount of oxygen in the air. And that varies even between different species of the same fruit. So a pink lady or a gala apple, they’ll have different requirements. So it’s kind of an astonishing thing. And then we get the stuff home and just throw it all in the fridge. And you know, a million post-harvest researchers just sigh because all the work they’ve done is now wasted. Well, it’s not wasted because it got the food to us. But yeah, the complexity of what it takes to figure out the exact perfect conditions for each item. You know, cheese, it likes it a little more humid. Other things like it dry.

MS: And it’s a fine line because, you know, sometimes I’m at the grocery store and I see a package of lettuce that looks worse for the wear. And I know, ooh, that lettuce was frozen at some point and now it’s no longer good. Or you grab a cucumber and it’s really mushy. And again, it’s not rotten, but I can tell like, oh, that was frozen. Now it’s thawed and it’s ruined. So it’s really easy to get this wrong.

NT: Oh, it’s really easy to get it wrong. And wrong in ways that also ruin the flavors. So you’re talking about things that are actually, you know, you don’t want a mushy cucumber. But, for example, if you put tomatoes at below 50 degrees Fahrenheit, they will switch off the mechanism that they use to produce flavor chemicals. So, that just happens.

And it is this really fine line between what will extend their life for the maximum amount of time without damaging how they look, how they feel, how they taste.

MS: How old is the food that I’m getting in the, in the grocery store? You know, if I’m thinking about the yogurt that I encounter at the grocery store and then the yogurt that you encountered when you were working at the warehouse. What’s the lifespan of a tub of yogurt, or another item?

NT: Well, that, no, that it’s a really good question. And a lot of times your food can be older than you think it will be. I always tell people if you’re buying an apple in June or July and it’s an American apple, we’ll just think for a second. When is the apple harvest? It starts in, you know, second half of August, runs through the fall. That apple is coming up on its first birthday. That apple, you, you might be cutting slices of it for your baby. It might be older.

MUSIC

MS: Nicola also says what’s on the shelves in the warehouse changes with seasonal demands…

NT: When I was working at Americold, we were building up pies for Easter. So you start building up kind of supplies of what is going to be needed in the stores a few months ahead of time. The way refrigeration functions a lot in our food system is sort of as this way of smoothing out the gap between supply and demand. So a factory wants to run at the same pace all year round because that’s the most efficient cost-effective way to do it. But, people eat more frozen pizza in the fall when it’s back to school and football season. And they eat more pies at Easter and they, you know, they eat more ice cream in the summer. And so the refrigerated warehouse ends up sort of smoothing out that gap and storing things for as long as it takes for us to want them.

MUSIC

MS: Having the ability to chill our food is still pretty new – but Nicola says it has completely transformed how we eat – more than any other modern invention.

NT: We’ve only really been able to control cold for about a couple of hundred years. We’ve only been using it to preserve our food on a sort of mass scale for just over a hundred years. It’s only been in our homes for that long. So it’s very recent and yet, it has been completely transformative. And um that’s really, in the end what the book is about, tracing how cold has managed to change what we eat, where it’s grown, how it tastes, how good it is for us, how good it is for the planet.

MS: The cold chain that keeps our food safe and fresh – that brings us salmon from Alaska, grapes and peaches from Chile, cheese from Italy – it requires a lot of energy to run…and creates greenhouse gasses.

NT: It’s a sad irony in that figuring out how to create all this artificial cold is basically set up the conditions where all of our natural cold, all our glaciers and, you know, the polar ice caps are melting. The two things are directly connected. And on one hand, it’s the energy issue. It takes a lot of energy to sort of transfer that energy out of the space that you’re trying to cool to elsewhere. And the other piece of this that I think, was totally surprising to me is the issue of the chemicals we use to do that process the refrigerants they’re called. And they turn out to be super greenhouse gases. They are multiple hundreds, thousands of times more warming than methane. So those are a huge problem and something that people are trying to figure out replacements for and trying to scale down. But that’s happening slowly. And so yeah, it’s, there are two pieces of the problem, both of which are kind of gigantic.

MS: Do you think we might see a whole revolution in our lifetimes of our food system where we come up with a whole new way? I mean, it seems unimaginable, but it certainly happened in the lifetime of my grandparents. So could it happen again?

NT: I think that’s what I hope my book will, will inspire. I mean, at my most optimistic, I want people to understand we transformed our food system with cold, but it was really recent. And it happened very quickly. And so the lesson to take from that is, well, actually, then we could do it again. And we could do it in ways that make our food system more resilient, more just, more healthy for us and the planet, that even deliver better tasting, more biodiverse food.

The problem, and this is the way the pessimist in me comes out, is refrigeration really is one of those things. You know, the expression, you know, if you’ve got a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Refrigeration will take care of preserving food. It just happens not to have great outcomes in many cases. And so I wish we could be a little more nuanced about it, whether we can be, I don’t know.

I do think that it’s going to be very hard in places that have already built and established and invested in a cold chain.

Where I hold out the most hope is the developing world. Most of the developing world does not have a cold chain at all. It’s rudimentary or not there at all. And those places are on the cusp of building a U.S.-style one. I went to Rwanda for the book. The government there has made building a cold chain one of its biggest priorities. And so my hope is, well, hey, just the same way that, you know, in Africa, they didn’t have to build landlines. They just skipped ahead to cell phones. Maybe they could do refrigeration better too. Maybe they could have a much more flexible, nuanced, not a one-size-fits-all solution. Use cold when you need cold. Use other things when that is what works. Think about the food that you want and the impacts that you want and design the preservation method to get those rather than saying, hey, I’ve got refrigeration. That keeps it good. I’m going to use that.

MS: Nicola Twilley is a journalist and the co-host of the podcast Gastropod.

Her new book is “Frostbite: How Refrigeration Changed Our Food, Our Planet, and Ourselves.”

BREAK

MS: We’re talking about the cold and the role it plays in our lives and food supply.

Frozen food is often associated with diminished quality – the kind of stuff that just tastes meh once you defrost it and prepare it. A far cry from the fresh stuff. But, a type of super cold freezer called “blast freezer” is creating a different flavor experience – and cutting down on food waste.

Zoë Read has more

[sound of freezer door opening]

ZOË READ: I’m at Small World Seafood in Philadelphia. Owner Robert Amar opens the door of one of his blast freezers. It’s stainless steel, tall, and has digital temperature displays… A cold mist lingers over trays of bright coral salmon filets.

ROBERT AMAR: If you put your hands on those trays without gloves, it’s like putting your tongue on a pole. You’ll get a little burn on your fingers. So you got to wear gloves to pull them out.

ZR: Robert uses these super cold freezers for most of his seafood: from salmon to trout, cod to scallops.

He says it ensures his products stay fresher longer. When you buy fresh seafood at the market, you have to eat it within a day. But his fish — frozen at temperatures much colder than a regular freezer — can be taken home and stored in your freezer for up to a year.

He also says his blast frozen fish tastes much better than regular frozen seafood.

RA: When your experience is only supermarket frozen fish … what are you going to think? Frozen fish sucks … Like if all you experience is buying bread in a supermarket, you think that’s what it is. But then, a French bakery opens up and you get a baguette and you’re like, ‘Holy crap, this is what bread is supposed to taste like?’ Now you can’t go back. You just have to taste it and see it first before you kind of can believe it.

ZR: The seafood department is one of the most wasteful sections of the supermarket, studies show. When customers don’t buy fish right away, the store has to throw it in the trash. Robert says using a blast freezer cuts down on that waste.

RA: We’re not going to fix the problem, we’re tiny. Because it’s a global issue. But, I don’t know, you know, you do what you can, right? Like everybody feels better about doing what they can. And it’s a start.

ZR: He says the fish must be blast-frozen as soon as it’s in the shop to ensure quality.

These freezers are not just colder – they also freeze things more quickly.

Jonathan Deutch is a culinary arts professor at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

JONATHAN DEUTCH: A typical freezer is at zero degrees Fahrenheit. And it takes things quite a while to freeze. You probably experience that in your home. You put something in the freezer and you check it an hour later and it’s cool to the touch, but it’s still not frozen solid. And, there’s nothing wrong with that. But from a food quality perspective, the quicker you freeze something, the better.

ZR: He says in a blast freezer, the ice crystal formations are much smaller, and won’t disrupt the cell wall structure of the food. So the texture of the product remains intact and preserves the natural properties of the food – which improves quality.

And Jonathan says it also slows down decay.

JD: Food, whether you’re talking about fish, meat, fruit, vegetables, is really decaying tissue, right? It’s cut off from its life source and it’s deteriorating. And sometimes we want to encourage that deterioration, right? If we’re cheesemaking or something, we want that aging process and that fermentation process to happen. And other times we want to prevent that. What freezing does is it really slows down those chemical and physical processes of that deterioration.

ZR: He says this method is preferable to so-called “fresh” seafood customers may see in grocery stores – a lot of which was actually previously frozen.

JD: They’re defrosted at the store because consumers have this idea that somehow refrigerated, quote unquote fresh is somehow better than frozen. And actually, the converse is true that buying frozen seafood is better from a quality and a safety perspective.

ZR: Blast freezers aren’t only used to store seafood. Pastry chefs use them to preserve the texture of their products, and some chefs use them so they can prepare food for the whole week.

Matt McKenney sells blast freezers to chefs and businesses across the Philly region. He showed me just how these chilly machines work by freezing raspberries

MATT MCKENNEY: What we’re looking at is some regular grocery store raspberries that were blast frozen at negative 30 degrees Fahrenheit.

ZR: When he takes them out, they’re hard like rocks.

MM: What we’re feeling is that the product is hard, but when you press it between your fingers, it crumbles. But it crumbles not into mush… But each individual section each little round segment of the raspberry is distinct.

ZR: No juice drips out of the berry. He calls it “raspberry caviar.”

He says fruit placed in a regular freezer loses the liquid that’s normally held in by those cell wall structures.

Then he pops a raspberry in his mouth.

[eating noises]

MM: The other cool thing about it is. I can chomp down on … and not break all the crowns in the back of my mouth. Which would happen with most frozen food, right?

ZR: During the pandemic, Matt co-founded a blast-frozen pizza company called Pizza Freak Co. He says because it’s blast-frozen, he doesn’t need to use preservatives and it has restaurant-quality taste. Customers who buy the pizza can store it in their home freezer.

These blast freezers aren’t universal yet — perhaps because of the expense. They can cost thousands of dollars.

But, Matt says they’re more common in Europe, which has stricter standards for freezing food.

MUSIC

MS: That was Zoë Read reporting.

Coming up… AC units make our homes and offices bearable in the hot summer months – but they use a LOT of energy. Now, engineers are trying to come up with a new generation of air conditioners:

MIKE STRAUCH: We kind of call this unit – there’s two shapes used to describe it – one is Tennessee, and the other is the Star Wars Sandcrawler, for anyone who knows Star Wars, it kind of has an angled slope on one side to maximize surface area.

MS: That’s next on the Pulse.

BREAK

MS: This is The Pulse – I’m Maiken Scott.

We’re talking about harnessing the cold and how that affects our lives.

Air conditioning made its public debut at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 – delivering cool temperatures to an auditorium in the Missouri State building. Engineer Willis Carrier had invented this “apparatus for treating air”.

By the 1960s – air conditioners had become more affordable – and started to be standard in new American homes.

VINTAGE COMMERCIAL: “This lucky baby will sleep quietly through the night. Yes, no matter how high the temperature goes outdoors, this baby’s RCA air conditioner will keep his room filled with cool, dry, fresh air and keep that room so comfortable and quiet, he’ll never need a middle-of-the-night lullaby.”

MS: They’ve changed the way we live, work, and sleep – but… if you’re running your unit during those hot summer months you know this: they use a lot of energy.

That’s a problem in a warming world – where more people rely on air conditioning to be able to function – and that’s not the only problem. Air conditioning also gives off heat – making temperatures outside even more unbearable.

Now, a race is on to develop new kinds of AC units that are more sustainable.

Alan Yu has more

ALAN YU: Engineer Sorin Grama got interested in air conditioning when he was working on a project in India – and lived there for a few years.

One of his colleagues complained that her daughter could not focus on her studies for school because it was too hot.

Sorin gave her an extra air conditioner they had lying around…

SORIN GRAMA: A few weeks later when I saw her again, I was very excited to see what difference it made. So I was, asked how is it going? How did you like it? And she kind of looked at me very sheepishly and she said we’re not using it because it’s too expensive to run.

AY: The experience got him interested in creating a more efficient air conditioner.

Air conditioners are notorious energy hogs.

That’s because they do two things at the same time: they dry the air, and cool the air

Think about how much more uncomfortable it is when air is hot and humid, as opposed to hot and dry.

So air conditioners suck the humidity out of the air, and bring down the temperature at the same time.

Sorin says this is not ideal…

SG: This is a hundred-year-old technology.

SG: Not much has changed since then. It’s basically the same basic technology. It does this cooling and dehumidifying in a very inefficient, brute method way basically overcooling the air in order to draw the moisture out of it.

AY: To remove the humidity, air conditioners chill the air so much that moisture becomes a liquid.

But that process makes the air far too cold for most humans, so the air conditioner has to heat the air back up again to the desired temperature

SG: That’s why all air conditioners drip water out and that cold water is basically wasted energy.

AY: This is where Sorin and other entrepreneurs come in…

SG: A lot of the industry’s starting to see the benefits of separating cooling and dehumidifying, and doing those two processes separately.

AY: His company, Transaera, made an air conditioner that contains a special material that is very good at absorbing moisture out of the air.

One of his colleagues described it as “sponges on steroids”

So his device does not need to cool the air to an uncomfortably cold temperature just to get the water out

He says that has the potential to save 40 to 50 percent of the energy compared to a traditional system.

SG: This can transform the way air conditioning is done and can achieve significant savings without making it more expensive than it already is.

AY: Transaera has millions of dollars of startup funding, including support from Carrier, the company widely credited with inventing modern air conditioning more than a century ago.

I got a chance to see this next-generation air conditioner in action.

It’s being tested in a lab in Maryland before it will be installed in a building for the first time.

The air conditioner is a big metal box that’s about the size of a very small car, like a mini cooper.

One side is sloped instead of straight, so the top part sticks out.

Product engineering manager Mike Strauch is part of the team that built this prototype by hand.

MIKE STRAUCH: We kind of call this unit – there’s two shapes used to describe it – one is Tennessee, and the other is the Star Wars Sandcrawler, for anyone who knows Star Wars, it kind of has an angled slope on one side to maximize surface area.

AY: He says a lot of effort went into this handmade air conditioner.

MS: There’s a lot of cuts and scrapes and bruises that have come from making it the way that it is.

AY: Mike says the team has become very attached to this unit, and this is the first time it has left their lab in the Boston area.

AY: Did someone ride in the truck from Massachusetts to here?

MS: We talked about it. I uh, I did actually strap my Apple air tag inside. So the two days when it was on its way here, I was checking Find My [iPhone] every few minutes just to see what rest stop it was stopped at.

AY: This air conditioner is designed to sit on the roof of a building.

It’s powerful enough to control the air temperature for an entire building.

But right now – Transaera is putting it through tests in the lab – in a simulated building with virtual people.

The unit sits inside a testing chamber that looks like a tall, 16-foot-long walk-in freezer

The temperature inside the chamber can be manipulated to recreate different seasons — everything from a chilly 20-degree Fahrenheit winter to a scorching 120-degree Fahrenheit summer.

The space inside the testing chamber represents the outside world

The virtual building full of people is represented by a colorful foam box – which is connected to the Transaera air conditioner

I got a tour from consultant Cara Martin.

She is the head of OTS R&D, the company that runs this lab and specializes in testing air conditioners.

AY: So I’m going to imagine that this thing is outside a building and that inside this foam box that’s turquoise on one side, purple on the other side. Like there is a whole building full of people in that.

CARA MARTIN: You got little mini people in there.

AY: Okay, and so like, you know, there’s like I don’t know like 100 office workers all sitting inside that typing away and so like you want to find out like what happens if you use this Transaera air conditioner to supply air to all the people in this like tiny office and what happens outside?

Mike Strauch: Exactly, yeah what happens, and then what are they doing inside that office space that changes the condition of the air that we receive back to our unit, and then we put that air to work, helping dehumidify the space.

AY: This first unit is meant for industrial uses, like a factory or warehouse.

But the team says you can use the technology for homes or even cars as well.

They hope to have a commercial product ready by next summer.

Their approach focuses on reducing energy use – but that’s one problem with our current air conditioning systems.

The second problem is that they use energy at a bad time — during the day, when it’s really hot, and everybody is turning on their air conditioners.

This was a big problem for engineer Daniel Betts, when he worked at energy companies.

DANIEL BETTS: Air conditioning was, how should I say, the most annoying load, meaning that air conditioners turned on at the wrong time

AY: It strains the electric grid, at a time when it’s already not functioning optimally.

Equipment that generates electricity and sends it out over the grid does not work as efficiently when it is hot outside, so people turn on air conditioners precisely at the moment when it is bad to strain the power grid

More than 10 years ago, researchers at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado came up with a solution which Daniel heard about…

DB: It blew my mind.

AY: He helped start a company, Blue Frontier, to turn that technology into actual air conditioners.

To understand how this works, think about evaporative coolers, which are also called swamp coolers.

A swamp cooler is a cheap air conditioner that works by using a fan to send air across a wet surface.

The water evaporates, and that takes some of the heat energy out of the air.

This is also why sweating can cool you down.

The downside is that swamp coolers only work in very dry climates, because the process also makes the air more humid.

Part of Blue Frontier’s solution is to create that very dry climate…

DB: The process of creating air conditioning is, I first pass air over the salt solution, the liquid desiccant.

That salt solution absorbs the water right out of the air, which creates this desert-like condition

AY: Combine that with a swamp cooler, and you have an air conditioner.

DB: However, I have another trick up my sleeves that a conventional swamp cooler does not have…

AY: The Blue Frontier air conditioner has a salt solution that draws water out to dry it.

But it can also use electricity to dry the solution back out at night, when there is not so much demand for power.

So it can draw electricity at a time when there is not as much demand for it, and put that to use later.

DB: This is important because then the air conditioner becomes sort of like a battery…

AY: That solves the problem of air conditioners turning on at annoying times.

It’s also good for switching to more renewable energy because humans cannot control when the wind blows or the sun shines.

Blue Frontier also has millions of dollars in start-up funding.

Daniel says they have some pilot units being tested in a few buildings, but hope to have a larger release next year.

MUSIC

AY: Creating the air conditioner for the future is an exciting field right now…

There are more companies, including existing air conditioner manufacturers, all trying to make the next-generation device.

It is an important effort.

The world already has an estimated two billion air conditioners right now.

But there will be even more of them – as temperatures rise, and people in developing countries are able to buy more air conditioners.

MUSIC

MS: That story was reported by Alan Yu.

You’re listening to The Pulse, I’m Maiken Scott – you can find us wherever you get your podcasts.

Coming up… why some people are choosing an eternal chill – in hopes of coming back to life one day…

JAMES ARROWOOD: Maybe it works out and you wake up one day in the future or maybe you don’t. But either way, you’re dead. So what do you care? And it’s kind of… fun.

MS: That’s next on The Pulse.

BREAK

MS: This is The Pulse – I’m Maiken Scott.

We’re talking about harnessing the cold – and how that has changed our lives.

The cold can do a lot for us — it helps us preserve everything from food to transplant organs. But when you think about how we talk about the cold in everyday language, it’s pretty negative. We call people who lack empathy cold-hearted. Somebody ruthless is cold-blooded.

We talk about cold shoulders, stone-cold killers, being left out in the cold. And we associate cold with the one thing lots of people fear: the final chill — death.

But out in the desert, in Scottsdale, Arizona, an organization is trying to harness the cold to do something that’s never been done: to cheat death. Liz Tung talked to a photographer who recently got an inside look at how exactly they’re trying to do that…

LIZ TUNG: Alastair Wiper is a photographer, with a penchant for the weird and quirky – and one day, his work took him to an underground bunker in Las Vegas — built in the 1980s by an eccentric millionaire.

ALASTAIR WIPER: And it was like a nuclear fallout bunker, but it was built like a real house underground.

LT: Honestly, more like a mansion…

AW: He had a swimming pool, and he had jacuzzis, and he had a golf, putting green, and the barbecue and all sorts of stuff.

LT: This would be weird enough for most of us – but then Alastair started seeing flyers throughout the bunker for something called the Church of Perpetual Life, which, as it turned out, is the owner of the underground mansion. Alastair was intrigued…

AW: They’re like a church that wants people to be able to live forever by cryonically freezing them and then bringing them back to life in the future.

LT: It sounded like something out of a sci-fi movie, like “2001” or “Planet of the Apes” or “Interstellar.” But after talking with a member of the church, Alastair found out about a group that’s trying to make cryonics a reality.

The Alcor Life Extension Foundation – a nonprofit started in 1972 by a husband-and-wife team, named Fred and Linda Chamberlain. Now, more than 50 years later, Alcor is still around — and still freezing people who want a chance at life after death. And Alastair desperately wanted to see what that looked like.

He ended up scoring an invitation to tour Alcor’s facilities – and in October of 2023, he found himself driving through the desert towards Alcor’s headquarters in Scottsdale, Arizona.

AW: Really hot. Blue skies. Very Arizona.

LT: Alcor says they chose Scottsdale because, more than just about any place else in the U.S., it has one of the lowest risks of natural disaster, like earthquakes, or hurricanes, or tornadoes.

Alastair drove through the desert till he hit a neighborhood filled with strip malls and low, blocky office buildings. Alcor’s headquarters looked the same — a concrete, one-story building with big glass mirrored windows.

AW: A few big palm trees kind of on the outside and maybe a cactus.

LT: In other words, totally normal.

AW: Yeah — if you didn’t know what was going on there, you would think it was like a completely normal place.

LT: Inside, Alastair was greeted by an equally normal-looking lobby — chairs, a front desk, magazines on the tables. But there was one detail that stood out…

AW: A few walls with pictures of some of the people that have been preserved…

LT: People ranging in age from two all the way up to their 90s… and even a few cats and dogs. All of whom were housed right there, in that building. Alcor doesn’t refer to them as bodies — instead, it uses the term “patients.”

AW: Because the idea is that one day they’re going to be alive again so they’re not, maybe they’re not really dead. They’re just being looked after.

LT: The first stop on Alastair’s tour was what looked to him like a converted kitchen, but was actually a combination lab and storage area.

AW: So there were two really big, industrial, gray, stainless steel fridges full of the chemicals that they used to preserve the bodies. And apparently, they’re very, very expensive.

LT: Ideally, after death, the body is immediately transported to Alcor, where it’s brought to the next stop on Alistair’s tour — the operating room.

AW: There’s a table in the middle of the room, and there’s lots of equipment all over it, and the table is a kind of autopsy table because it has kind of drains down the side, which I assume is so that bodily fluids can drain when they’re preparing it to be preserved.

LT: I talked with James Arrowood, the CEO of Alcor, and he told me that this room is indeed where some of the most important prep work for preservation happens — a process called “vitrification.”

JAMES ARROWHEAD: So their body is actually connected to a machine and that machine perfuses the body with this chemical. It’s called a cryo-protective agent or a CPA.

LT: Kind of like a medical-grade antifreeze that replaces all the water in your body — the blood and fluids that are drained out. And James says these cryoprotectants are similar to what you’d find in a lot of fish and amphibians.

JA: That in nature, they’ll freeze but then they thaw out and they’re still alive. Well, how does that happen? They actually have some little proteins in their blood, and those proteins in their blood protect their cells from damage, from ice nucleation, from the freezing process.

LT: Once that’s done, the patients are wrapped in a plastic sheet and lowered into a “cooling box” filled with liquid nitrogen. There, a fan circulates the vaporizing liquid nitrogen, which in turn draws heat from the body. The cooling process takes a while — around 5 to 7 days. At the end of that process, the body is vitrified — meaning it’s been turned into a solid, at a cool temperature of -196°C, or -320°F.

At that point, the bodies are moved to their final holding destination — and the main attraction for Alastair’s tour — the “patient care bay.”

Which is where the bodies are stored in big metal containers called dewars.

AW: They’re a bit like, if you’ve ever been to a brewery and seen beer being made – they’re kind of like the big fermentation tanks that you have there.

LT: Each dewar contains up to four, nine, or 12 bodies, all placed vertically, and upside down in a circle.

AW: And then in the middle they have a kind of column which they can pull out, which has only got heads.

LT: That’s because — not everyone opts to get their whole body cryonically preserved since that costs $220,000. A cheaper option, for just $80,000, is to only have your brain preserved, like the talking heads of Futurama.

The way Alcor preserves these bodies and heads is by using liquid nitrogen, which has the advantage of not only keeping them super cold, but keeping them super cold without the need for electricity. Which, Alastair explained, is why the bodies are stored upside down.

AW: The reason that they’re upside down is that if anything ever goes wrong, like for instance, there’s some kind of nuclear apocalypse. And no one is there to top up the liquid nitrogen and look after the patient care bay. Then gradually the liquid nitrogen that’s in the dewars would evaporate and the level will get lower and lower and lower. And the last thing that will be covered by liquid nitrogen would be the head, and the head is the most important part because that’s where the brain is. So they’re trying to apocalypse-proof it as much as possible.

LT: Now, you might say there’s something undignified about being stored upside down in a giant thermos… to say nothing of being awoken in several hundred years, confused and possibly just a head. But, after talking with some of Alcor’s staff members, who plan on being cryonically preserved themselves, Alastair came to understand that, for the true believers, a little indignity is nothing compared with the possibility of eternal life.

AW: There’s a kind of a wide spectrum of reasons for doing it.

LT: I waited with bated breath to hear those reasons — a pathological fear of death? A burning passion to see the future? A desire to probe the boundaries of our metaphysical existence?

AW: One of the reasons is, why not?

LT: I talked with James, the CEO of Alcor about this — and he explained that the whole “why not” attitude isn’t because people make the decision lightly, or happen to have a ton of extra money lying around. It’s because they want to become pioneers of the possible… All while knowing full well that, right now, reviving frozen, dead subjects is not possible — and there’s no guarantee that it ever will be.

JA: And I hear a lot of criticism of that somehow Alcor is offering people false hope, or promising that they’re going to come back someday. We do not.

LT: In fact, at the moment, they don’t even know for sure that even if revival were eventually made possible, that the vitrification process adequately preserves the brain.

But, James says, if it ever is to become possible, research needs to be done. And that is what this is… a big science experiment that Alcor’s members want to be a part of, even if it never results in their own revival.

JA: We have 1500 members and out of those 1500 members, there’s 10% that believe it’ll never happen. There’s 10% who are convinced it absolutely will happen. And then there’s 80% of the people in the middle who don’t know, but they figure it’s better than cremation and it’s better than burial. And if it never works, if we even just do the organ banking on simple organs like kidneys, then they want to contribute and have their legacy be helping save lives of other people because that may be their great-grandchild someday.

LT: James compares it to donating your body to science — being part of something bigger. And offering yourself the best thing we can hope for in death — a chance, however slim, of living again. Here’s Alastair.

AW: You know, if you die, you’re going to be cremated or you’re going to be buried and then you’re probably gone forever. Whereas if you do this, then you have nothing to lose. Maybe it works out and you wake up one day in the future or maybe you don’t. But either way, you’re dead. So what do you care? And it’s kind of… fun.

LT: I asked Alastair if, after seeing the good, the bad, and the ugly of cryonic preservation up close, if he’d ever be interested in doing it himself.

AW: No. I’ve thought about it, but I feel, I feel like I’m quite at peace with the fact that when I die, I’m gone and I will disappear into the ether.

I’m not religious at all. But it seems kind of natural to me that I’m going to die at some point. That’s like the cycle of life.

MS: That story was reported by Liz Tung.

MUSIC

That’s our show for this week — The Pulse is a production off WHYY in Philadelphia – made possible with support from our founding sponsor, the Sutherland Family, and the Commonwealth Fund.

You can follow us wherever you get your podcasts.

Our health and science reporters are Alan Yu, Liz Tung, and Grant Hill. Lauren Tran-Muchowski is our intern. Charlie Kaier is our engineer. Our producers are Nichole Currie and Lindsay Lazarski.

I’m Maiken Scott, thank you for listening!

collapse

Segments from this episode

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by The Pulse

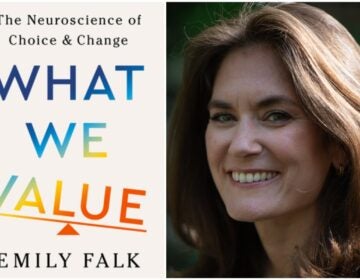

The Neuroscience of decision-making

Why don’t we always prioritize what matters most—like making time for family and friends or fitting in a workout during a busy day? ...

Air Date: September 12, 2025 12:00 pm

Listen 50:01Podcast Extra: Odd Couples and the Science of Attraction

An exploration of the mysteries of attraction and the science of optimizing online dating.

Air Date: September 9, 2025

Listen 37:17Mars Mania: How America Became Obsessed with Mars

Tracing the history of our obsession with Mars, from modern efforts to colonize to belief in a Martian civilization.

Air Date: September 5, 2025

Listen 50:03