Pa. could vote on Marsy’s Law: Here’s what’s at stake

Would a Marsy’s Law amendment on victims’ rights infringe on bedrock rights of the accused? The last-minute legal fight over a question on the Pa. ballot.

Listen 15:21

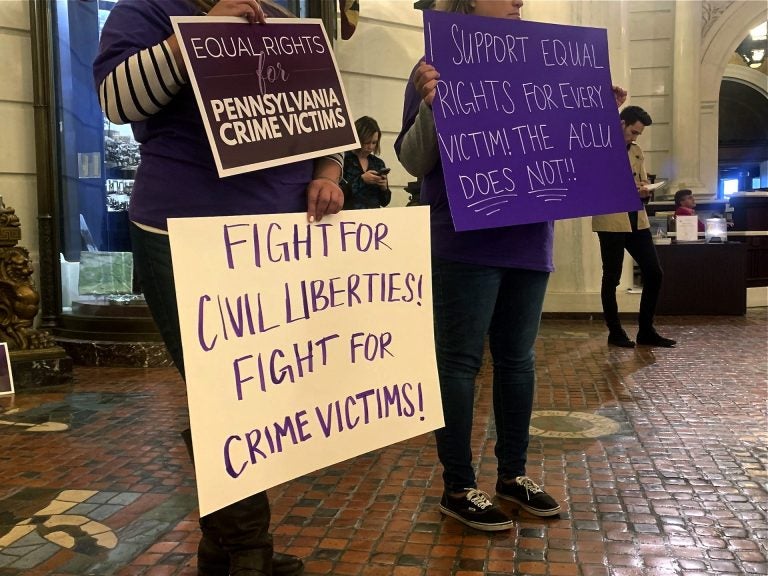

Supporters of Marsy's Law held signs in protest during the ACLU's press conference announcing its lawsuit. (Katie Meyer/WITF)

Listen to The Why wherever you get your podcasts:

Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Stitcher | RadioPublic | TuneIn

By Meir Rinde

Updated: 2:15 p.m.

—

A judge ruled Wednesday that votes in a referendum next week about enshrining victims’ rights in Pennsylvania’s constitution will not be tallied or certified while a legal challenge is pending.

Voting “yes” on the ballot question would add a list of 15 victims’ rights to the constitution, including the right to be notified of legal proceedings involving the alleged perpetrator, to speak during trials and parole hearings, to demand speedy trials, to refuse requests for pretrial evidence, and to receive restitution.

Eleven states have added versions of this measure, called Marsy’s Law, to their constitutions. It’s named after Marsalee Nicholas, a California woman who was murdered by her ex-boyfriend in 1983. Her brother, tech billionaire Henry Nicholas, lobbied for the first Marsy’s Law, which passed in California in 2008, and funded campaigns for amendments in the other states. The Marsy’s Law for Pennsylvania committee reports receiving $3.6 million in financial and in-kind donations from Nicholas’ California-based organization.

Like all constitutional amendments placed before voters, the measure passed the Pennsylvania House and Senate in two consecutive sessions. But less than a month before the Nov. 5 election that will decide whether it becomes law, the ACLU of Pennsylvania sued to block the ballot question.

Arguing on behalf of the League of Women Voters and an individual voter, the ACLU said the question violates the constitution by packaging together several changes that should be voted on separately, a practice called “logrolling.” A lawyer for the state argued in court last week that the question should pass muster because all its parts are aimed at the same purpose of boosting victims’ rights.

Commonwealth Court Judge Ellen Ceisler issued a preliminary injunction Wednesday to block the votes from being counted until the legal case plays out. (Tuesday’s ballots have already been printed, and more than 20,000 absentee voters have already weighed in.)

Ceisler said she granted the injunction because the amendment would have immediate, profound and in some cases irreversible consequences for the rights of accused people and the criminal justice system.

“If approved by a majority of the electorate, every stage of the criminal proceedings, including bail hearings, pretrial proceedings, trials, guilty pleas, sentencing proceedings, and parole and pardon reviews, will be put into doubt,” Ceisler wrote.

‘Two competing sets of rights’

The state’s Crime Victims Act, passed in 1998, already provides a similar set of privileges and established an Office of Victim Advocate. But supporters of the amendment argue that victims still sometimes do not receive notifications that an accused person is out on bail or due in court, or do not have an opportunity to give a statement during sentencing.

“In all the time that we have tried to pass laws, it still slips through the cracks,” said Rep. Sheryl Delozier, a Cumberland County Republican who sponsored Marsy’s Law in the Pennsylvania House. “It still requires saying, ‘Oh, I’m sorry we can’t help you with this because victims don’t have those rights.’ So by putting it in our constitution, we won’t have to say that ever again, because those rights will be enshrined in the constitution.”

But critics say it is not clear that Marsy’s Law will result in improved experiences for many crime victims during criminal prosecutions.

For example, the amendment does not provide a mechanism for ensuring that victims get the required notifications, and it bars them from suing prosecutors or other government officials for damages if its requirements are not fulfilled. Elizabeth Randol, legislative director for the ACLU of Pennsylvania, said a victim who believes his or her rights are being violated would have to hire a lawyer to argue that point before a judge.

More fundamentally, adding victims’ rights to the state constitution will create a conflict with the bedrock concept of the rights of the accused, she said.

In criminal cases, individuals have rights to due process and fair trials to defend themselves against government overreach. But giving victims new rights, such as allowing them not to provide pretrial evidence that could exonerate a defendant, could impinge on the basic rights of people who have been charged but not yet convicted of a crime, Randol argued.

“Our concern is that there are these broadly construed rights that we’ve never had before in the constitution that would set up two competing sets of rights between the accused and the victims, and with no sense of how those how conflicts between those rights would be resolved,” she said.

A demand for recognition

The story behind Marsy’s Law is an encounter that occurred after Marsy Nicholas’ killer was arrested and released. Her family had not been informed that he was out on bail.

“Right after the funeral, my mother was in the supermarket buying a loaf of bread. She went up to the checkout stand, and there was my sister’s murderer, staring her down. He would drive around our neighborhood in a convertible, flaunting,” Henry Nicholas recalled in a 2010 interview.

In Pennsylvania, district attorneys routinely notify victims or families of legal developments, but gaps in notification continue to occur. In July, Rafael Robb, a former University of Pennsylvania professor who served a prison term for killing his wife, Ellen, was granted permission to travel abroad while owing their daughter millions of dollars in damages. Ellen’s family was not initially notified and reacted with alarm when they learned of the decision. A prosecutor objected, and Robb withdrew the request.

The lack of notification reportedly resulted from an oversight that has been corrected by a change in state Department of Corrections procedures. But the Robb case has been cited as evidence that the state needs stronger victims’ rights laws.

For people who have been victims of crime and their families, such incidents feel like revictimization and illustrate the legal system’s failure to acknowledge their role in criminal cases, said LaQuisha Anthony, an education and training specialist at Women Organized Against Rape in Philadelphia.

Anthony, herself a rape survivor, argued that the justice system fails victims when it recognizes the rights of perpetrators who choose to commit crimes, but not the rights of those who are involuntarily made into victims.

Crime victims she knows are dismayed by the ACLU’s effort to block the Marsy’s Law ballot question, seeing it as one more effort to deny them their right to be heard, she said.

“It is just very disheartening, and it does come down to that for many people — that you’re not supporting us. That is what I’ve been hearing from the victims and the survivors that I work with, that what it shows is that those who commit crimes have more rights. Those who commit crimes are more valuable. Those who commit crimes are taken care of by the system. And yet victims are not,” she said.

“They want to feel like they matter. They want to feel like … they have the same access as someone who actually did something to them,” Anthony said. Victims want “equal rights,” she said, but currently the justice system seems to say that an accused perpetrator “might be a little bit more valuable than you are.”

Repercussions in other states

The legal recognition of the victim’s role that Anthony seeks is one of the main concerns for the League of Women Voters and the ACLU. Even before a judge or jury has decided whether a crime occurred and the accused is guilty, Marsy’s Law requires the justice system to identify victims and grant them certain privileges, such as advanced notification of legal proceedings, Randol said.

“What happens if a victim isn’t available? They might be traveling or away on business. Does the right to notification, to participation, in that part of the process supersede or override the (rights of the) person who’s now sitting in jail waiting on bail or who can’t make bail, and continues to sit in jail waiting for the proceedings to proceed?” she asked.

After South Dakota adopted Marsy’s Law, some defendants sat in jail for days or weeks, even for minor crimes, as they waited for victims to be notified of bond hearings, the Argus-Leader newspaper reported. Prosecutors and law enforcement agencies were overwhelmed by their notification obligations.

Last year, South Dakota voters approved a modification that aimed to ease the administrative burden by requiring victims to opt into many of their rights. Randol noted that current Pennsylvania law requires victims to register for notifications, but the Marsy’s Law amendment does not.

In some states with Marsy’s Law, victims have pressed for speedy trials, which in death-penalty cases could conflict with defendants’ right to seek legal relief through appeals, Randol said. In Florida, the amendment gives convicted people two years to complete their appeals, or five years in death-penalty cases. The Pennsylvania law does not mention specific time limits.

And Randol said that while the law’s vague language makes the potential effects unclear, it could be interpreted as allowing an alleged victim to refuse to provide evidence that shows an accused person is innocent.

Delozier rejected the charge that Marsy’s Law would diminish the rights of defendants, saying it will merely require judges to consider the rights of victims as well.

“I wholeheartedly don’t see where any rights of the accused are being taken away. I think that anything that comes through this system, with this law, will be in the judge’s hands and the judge can make that determination. And that is where our decisions are made in our judicial system, and that’s what’s fair,” she said.

Randol said another issue is the broad definition of victim. In Ohio, a city government used Marsy’s Law to seek financial restitution from a man who made a false 911 call, arguing that it was a victim in the case. A court overturned an initial order to pay restitution, and the city is appealing to the Ohio Supreme Court. In North Dakota, police officers who have shot civilians have used the law to prevent release of their names, which critics say diminishes police transparency. In Florida, some law enforcement agencies began refusing to release victims’ names after the state’s constitution was amended last year.

Randol said that rather than pass a constitutional amendment that raises so many potential red flags, Pennsylvania’s General Assembly could pass regular legislation to improve the existing rules and set aside more money for programs that aid crime victims.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.