Zoning remapping reality check

The Nutter Administration sees the planning and zoning reforms accomplished on its watch as a legacy achievement – from the citywide comprehensive plan and progress on individual district plans that chart out new futures for all neighborhoods, to a complete overhaul of the 50-year-old zoning code.

But if you listen through the backslapping and applause, there’s a lament. If we’ve come so far, how come it still feels like we are stuck struggling with many of the same challenges and dysfunctions these reforms were intended to alleviate?

Many neighborhoods are still banging their heads on familiar issues – oversaturation of student housing, overbuilt residential projects, sputtering commercial corridors. Developers are still exploiting obsolete zoning to get what they want at the Zoning Board of Adjustment, which is a morass of piecemeal thinking that has yet to embrace our era of reform.

While it’s tempting to think the hard work is behind us, we’re really only halfway done. Eight out of 18 district plans are finished, two more are just getting under way. Meantime, the planning commission has spent recent years working with neighborhoods and district council members to update the city’s zoning map – the color-coded, parcel-by-parcel guide for what’s permitted, where – to get rid of outdated zoning and help advance goals articulated in each district plan. I tend think of zoning remapping as the love child of district plans and the new zoning code.

We’ve heard for years that if the city’s zoning better reflected reality there wouldn’t be so many protracted neighborhood zoning battles. Developers would have greater certainty about their projects. Homeowners wouldn’t get tangled up in unnecessary bureaucracy. The process of remapping is painstaking and plodding.

But even intelligent zoning isn’t a silver bullet. So it’s important to be clear about what constrains the remapping process, and to be realistic about what we can reasonably expect updated zoning to resolve and what it can’t change.

REMAPPING PACE & POLITICS

REMAPPING PROGRESS TO DATE:

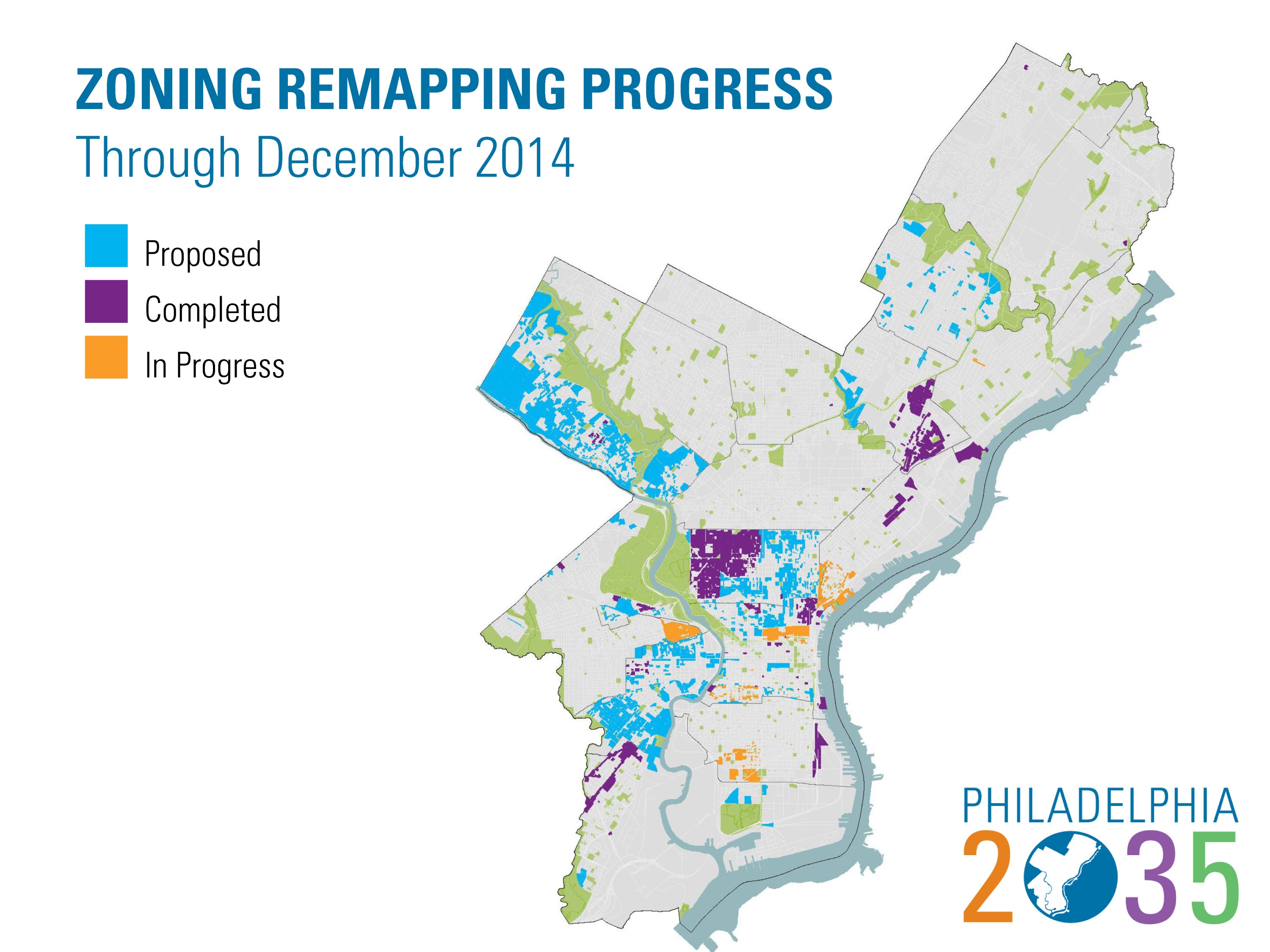

Zoning remapping has been proposed for 24% of the land area in the eight completed district plans. Of that, 26% has been remapped to date and another 8% is in progress.

REMAPPING BY DISTRICT PLAN:

Lower Northwest (passed Dec ’14)

- 40% of plan area proposed for remapping

- 1% complete

Lower North (passed Spring ’14)

- 43% of plan area proposed for remapping

- 57% complete

Central Northeast (passed Spring ’14)

- 7% of plan area proposed for remapping

- 0% completed

University Southwest (passed Summer of ’13)

- 40% of plan area proposed for remapping

- 2% complete

Central (passed Summer of ’13)

- 21% of plan area proposed for remapping

- 27% complete

Lower Northeast (passed in Fall of ’12)

- 17% of plan area proposed for remapping

- 68% complete

West Park (passed in Winter ’12)

- 6% of plan area proposed for remapping

- 18% complete

Lower South (passed in Winter ’12)

- 1% proposed for remapping

- 0% complete

SOURCE: Philadelphia City Planning Commission

The biggest practical constraints to updating zoning citywide are resources and political resolve.

To planning commission director Gary Jastrzab, “remapping is many wills: it is political wills, it’s community will,” and those expressions are supported by the planning commission’s technical skills. Harmonizing those wills, ground-truthing zoning changes, and crafting legislation with City Council staffers takes precious time and energy.

“A process like remapping takes years in major cities,” said Eleanor Sharpe, deputy director for legislative affairs at the planning commission. “It’s an iterative process to ensure that it gets done right, so you have consensus and people are not freaking out.”

The planning commission estimates each remapping takes about 150 hours of staff time to complete.

Each district plans makes a series of zoning recommendations, some are to align zoning with how properties are actually used, while others are aspirational – like high-density mixed-use zoning around transit stops. The remapping process picks up where the plans leave off, taking on those recommendations and reworking them as conversations with district council members, and neighbors continue.

To Jastrzab zoning remapping is “like doing open heart surgery. You want to keep the patient alive but you want to make corrections.”

At the neighborhood level remapping is also about making necessary changes, pushing for a bit of change, but often it is about leaving well enough alone. As former South of South Neighborhood Association program coordinator Andrew Dalzell explained, remapping is about finding the “right playbook… to get through the non-controversial changes and the ones that we think will have a really lasting impact in the interior of the neighborhood.”

The poky pace of remapping is gathering steam. In 2012 Council passed just four zoning remapping bills. By the planning commission’s count that number went up to 16 in 2013, and this year it doubled to 32.

In the eight completed district plans, about 24% of the land is proposed to be remapped. To date the city has completed remapping for 26% of proposed corrective and aspirational zoning recommendations and another 8% is in progress.

This summer City Council asked the planning commission what it would take to speed the process up. The commission estimated that it would cost $3.3 million over three years to complete zoning remapping. That funding would let the commission hire nine junior staffers and bring its budget nearly back to what it was in 2008. It remains to be seen if City Council will find that extra $1.1 million annually for the commission.

But the commission’s resources are only one constraint – like Jastrzab said, remapping is also a reflection of political will. For any zoning changes to advance, council members must make zoning remapping a priority in their districts. That’s the only way the planning commission can initiate a remapping process and the only way a remapping bill can ultimately pass City Council.

Some council members have jumped on board as each plan is completed. Others seem to prefer the convoluted way the development process works today. It forces zoning changes to flow through their offices and ensures a community meeting where neighbors can weigh in on variance requests – often the only opportunity to discuss a development at all.

Unfortunately the careful pace of remapping, and spotty support by City Council, means different neighborhoods are being treated unevenly. This lag also leaves ample room for savvy developers to flex the zoning process to their advantage, taking their chances at the ZBA to advance projects that neither conform to existing zoning nor the aspirations of neighbors articulated in district plans. That’s a particularly frequent frustration for neighborhoods where development pressure has been strong.

REMAPPING RELIEF

The vast majority of remapping recommendations are to get rid of outdated zoning. Parks should be zoned as parks. Long-time single-family residential buildings should no longer be zoned as multi-family. These changes are the remedial meat and potatoes of remapping.

“That’s where relief will come from,” Sharpe said. Corrections will simplify permitting and plan examination at Licenses and Inspections and save owners of incorrectly zoned properties unnecessary trips to the Zoning Board of Adjustment.

One of the biggest corrections the city can pursue is to relieve many neighborhoods of outdated industrial zoning to make way for different sorts of development.

Come January, the district planning process will begin for the River Wards, but Fishtowners have already been working with the planning commission to recommend new base zoning for the neighborhood.

“We just wanted to simply correct base zoning to prevent surprise by-right development that did not fit in with the neighborhood,” explained Matt Karp, chair of Fishtown Neighbors Association’s zoning committee.

They want to get out of this pattern: Developers continue to propose residential projects on old industrial sites. To do that they need a use variance, but can still take advantage of the more favorable conditions that come with industrial zoning, including taller heights and reduced setbacks. That, Karp said, was effectively letting developers have their cake and eat it, too.

As ex-industrial sites are remapped “to a more appropriate zoning given neighborhoods’ desire and the current state of the market, there is a good chance that the developer who wants to do some kind of mixed-used development on an industrial parcel won’t need to appeal. They will be able to do it by right or they will be able to do it with just minor variances that are not going to require a major effort by the neighborhood or developer to have that site developed. That’s the goal,” explained Jastrzab.

WHAT REMAPPING WON’T RESOLVE

Even with smartly tailored zoning citywide, there’s still plenty of room in our development process to account for evolving market conditions, political intervention, creative zoning interpretations by L&I, and a Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA) that remains happy to oblige developers. And in a sense, that’s just messy old democracy.

That’s also why zoning variance requests will always be part of the process, although remapping will theoretically reduce the volume of variances that require resolution at the Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA). The theory is that if zoning is clearer and more accurate, there will be fewer permit refusals at L&I that result in variance requests. It should make the development process more predictable and fair.

Strictly speaking, variances should only be granted to alleviate some kind of hardship. But the Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA) is still in the habit of handing out variances like candy on Halloween, in part because outdated zoning is so prevalent. Developers are willing to push projects toward a hearing before the ZBA because some 90% of the time they win approval.

Remapping should shrink the volume of cases that go before ZBA but it won’t give ZBA a spine. We need that board to be guardians of reform as zoning changes.

While it’s tempting to think updated zoning will lead to ironclad clarity, Jastrzab offers me this reality check: “Zoning is not a surgical tool, it’s a blunt instrument.” It sets the table, but it doesn’t cook supper.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.