Your child has asthma. Now what?

Work with the doctor to set a plan of action, so everyone breathes easier. That may include eliminating triggers in the home, a not-always-simple task.

Many children with asthma use daily medication like an inhaled corticosteroid to maintain expandable airways. (Duplass/BigStock)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

Most kids with asthma lead normal lives. If necessary, they use daily medication like an inhaled corticosteroid to maintain expandable airways. And, when needed, a bronchodilator helps open up their air passages when the medication can’t do the job.

For about 10% of all people with the condition, however, asthma is their life, said University of Pittsburgh researcher Kathryn Blake. If their asthma is not well treated, “the function of their lungs will change,” and they have the highest risk of dying from the disease.

“We are talking about kids who change their activities, they are waking up one or two nights a week” because of breathing problems, said Reynold Panettieri Jr., vice chancellor of the Rutgers Institute for Translational Medicine. “They didn’t sign up for baseball, soccer, can’t play a wind instrument.”

They do end up in the emergency room for treatment, missing school for days, even weeks, because they can’t control their asthma flare-ups. And where kids go, parents go, missing work, needing babysitters, juggling all sorts of things.

Even though researchers have learned that the condition can develop in several ways, most children with suspected asthma are still treated as if only allergies are involved. Yet they could have inherited their asthma; or be sensitive to some food; or have eczema, also known as atopic dermatitis.

Specialists such as Alfred F. Tallia, chair of family medicine and community health at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, wants clinical practice to catch up with current science.

“Now we have to ascertain what is going on, whether it’s more allergic, if there is an immunologic component, or a combination,” Tallia said. Experts also know that there are different levels of asthma severity, he noted.

So the challenge is getting this new information where most young asthma patients are treated — in a family physician’s or pediatrician’s office.

“There is a lot of education we have to do, especially with the biologics,” medicines that target specific molecules to thwart disease, Tallia said. Blood tests discern which molecule is involved. Only one of these biologics is Food and Drug Administration-approved for children 6 years and over, however.

There’s also more to learn, the asthma experts said — like practical ways to increase awareness of the symptoms and how to get better readings for kids on tests like spirometry, in which you breathe into a tube hooked up to a computer that calculates how much air you inhale and how much you exhale, as well as how quickly you exhale.

Kurtis Elward, a family physician in Charlottesville, Va., and a member of the 2007 National Institutes of Health Asthma Guideline Implementation Panel, said written action plans empower and educate parents.

“It’s been shown that when you collaborate with patient and parent, writing a stepwise plan for how to handle maintenance, emergency care, and times when the patient may be losing control … is well worth the effort.”

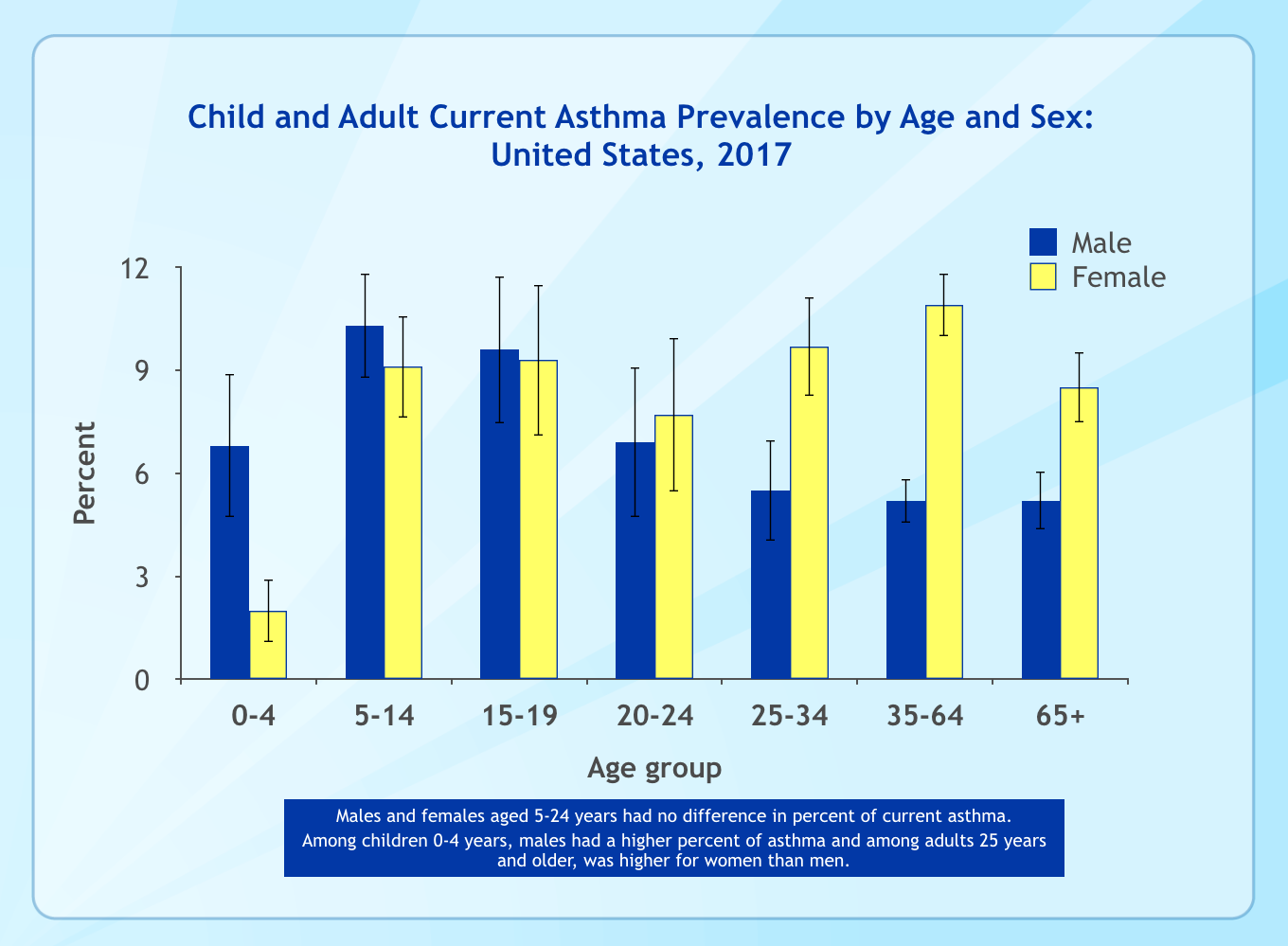

Experts are concerned because more people of all ages are affected. About 25 million people, or 8% of the U.S. population, had asthma in 2017, compared to 20 million, or 7.3%, in 2001.

Day-to-day challenges

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s asthma web page says some possible causes for the uptick are increased air pollution; homes with less ventilation, more moisture, and more indoor pets; and kids generally spending more time indoors.

While physicians and researchers are eager to match a correct diagnosis to each patient, it’s parents who deal with the day-to-day consequences of chronic illness, as illustrated by the stories told in a Facebook group for parents of kids with asthma.

A toddler without asthma might have a tantrum and her parents can choose to ignore it. Not so much if your toddler has asthma. One parent described her son’s distress over wearing his seat belt because of the belt buckle. He felt like he couldn’t breathe, his mother wrote, but he couldn’t ride in the car without it. He cried so hard, he had an asthma attack. They missed the birthday party they planned to drive to.

Another parent wrote about her child’s hair loss from too many medications. When another parent asked for help getting her 12-month-old to wear a mask for his breathing medication, there was advice at the ready: Get everyone in the family to wear a mask, and then do goofy things.

And one parent asked the group: Do any of you have PTSD (post-traumatic stress syndrome) from being the parent of a child with asthma? That question got 106 comments and 57 likes.

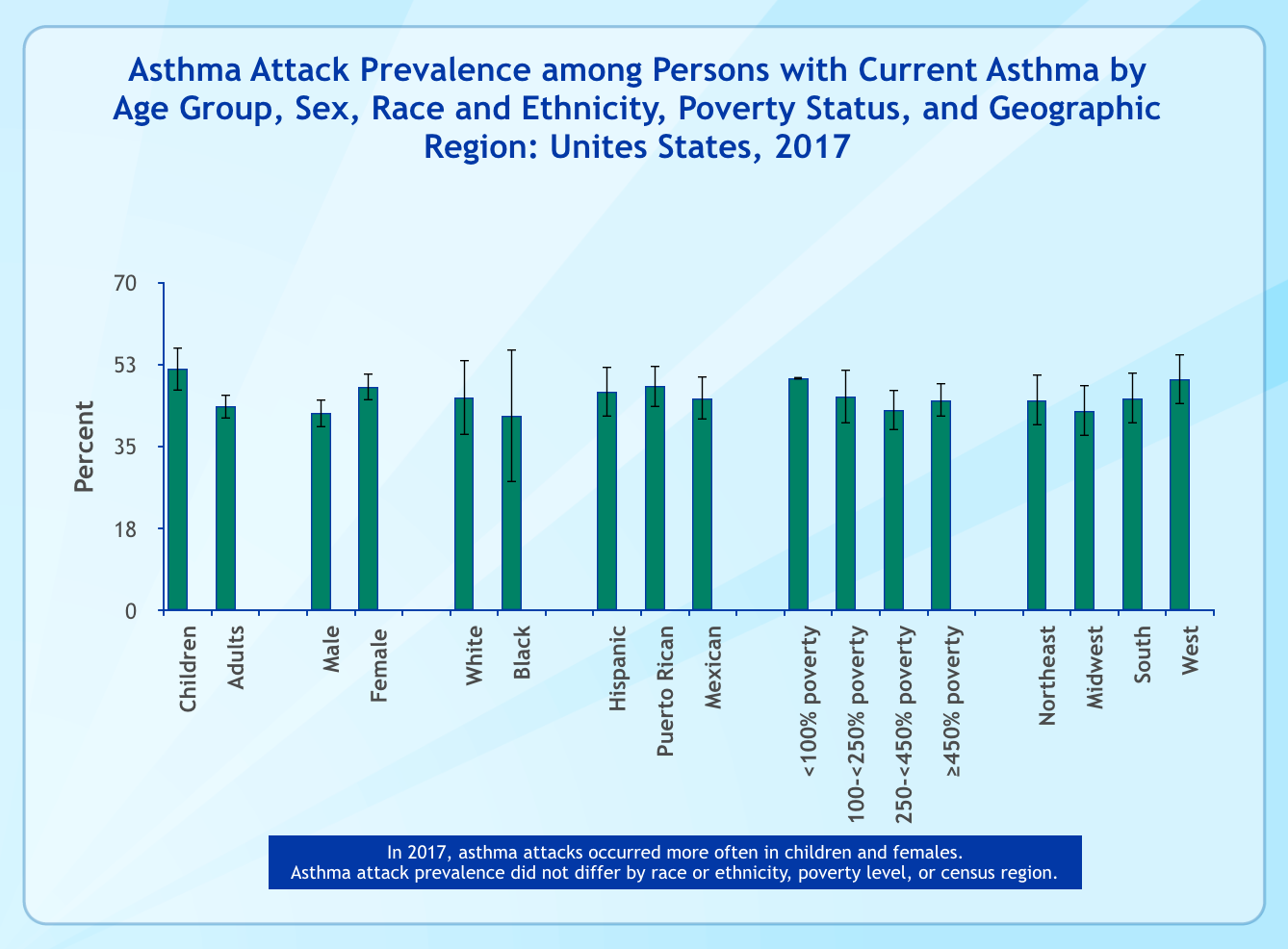

These days, more children are being treated for asthma in emergency rooms, and they are being diagnosed at earlier ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that in 2016, 1.8 million people received care for asthma in emergency departments, even though the prevalence of asthma attacks, or exacerbations, has been going down. In 2001, 61.7% of children and 53.8% of adults with asthma had at least one exacerbation in the prior year, compared with 51.6% and 43.6% in 2017. The rate of death from uncontrolled asthma has held steady at 11.2 per million since 2008.

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Maryori Canales, a community health worker, said some asthmatic youngsters she sees in West Philadelphia have missed weeks of school because of uncontrolled exacerbations.

“Studies have shown that severe asthma accounts for an outsized proportion of the disease-related morbidity, mortality and health-care costs,” Panettieri and colleagues including Sally E. Wenzel, chair of the University of Pittsburgh’s Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, wrote in a journal article last fall discussing the condition among patients of all ages.

An earlier study noted that 11% of children in primary-care settings are wrongly prescribed inhaled corticosteroids, while many of those with asthma-like symptoms are under-diagnosed. There are many reasons why, not the least of which is that kids still have developing immune and respiratory systems, and they also have small airways.

Yet research and existing programs have shown that with education, implementing a plan and follow-up, severe asthma can be controlled. For example, in Finland a national program to improve care and stabilize costs reduced the number of hospital days by 54% (110,000 in 1993 to 51,000 in 2004), with the numbers still dropping.

At Rutgers, Tallia, Panettieri and their team plan to reach those who treat asthma in New Jersey via a webinar to discuss new approaches. They are focusing first on adult patients, teaching family physicians and others about the new biologics. Rutgers is working with Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield in this project — a patient won’t need pre-approval if he or she can benefit from one of the five new medications.

Wenzel and asthma researcher Barbara Yawn, a physician and adjunct professor in the Department of Family and Community Health at the University of Minnesota, are also writing an online webinar to help family physicians figure out if a patient has severe asthma or something else. These doctors need better-defined and practical ways to identify people with severe asthma, Yawn said. Then they can decide, “Should I evaluate further, or send to special colleagues like allergists and pulmonologists?”

At-home steps can help

CHOP’s Canales said proper medication use is always an issue with the families she works with. Either the children take too much, the parents withhold the daily medication because the child is doing well, or the parent fears the steroid will affect the child’s growth and development. Then triggers in the home set in, “and then I know why the child is spending a lot of time in the hospital.”

On subsequent visits, however, after the parents have heard that following medication directions will reduce hospital visits, “I do see a difference,” Canales said.

“Our model has held up for many years,” said Tyra Bryant-Stephens, the physician who founded CHOP’s Community Asthma Prevention Program 22 years ago.

Community workers like Canales visit families for a year through CAPP, and then the families are enrolled in a state-supported program. Bryant-Stephens said the community workers and the families focus on physician-written action plans for each child, to make sure they are understood and carried out.

Children’s Hospital, along with its partner, the Philadelphia Housing Development Corp., have finished the pilot phase of its CAPP+ project, a CHOP representative said. Since January, workers have rehabbed 10 West Philadelphia houses belonging to CAPP families to eliminate the kinds of triggers — faulty plumbing, wet basements, pests that require serious extermination efforts, for example — that can make it tough for kids to breathe. The goal is to rehab 100 houses within the year, Bryant-Stephens said.

Canales said she has entered houses in such disrepair, the walls were falling down.

“The societal and economic [issues] are controlling the child’s asthma maintenance,” she said. “There are so many things to factor in to help a parent.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.