Young Philly activists endure the ups and downs of their first march on Washington

Saturday’s rally was framed as both a protest against gun violence and a galvanizing moment for teenage activists.

Listen 5:46

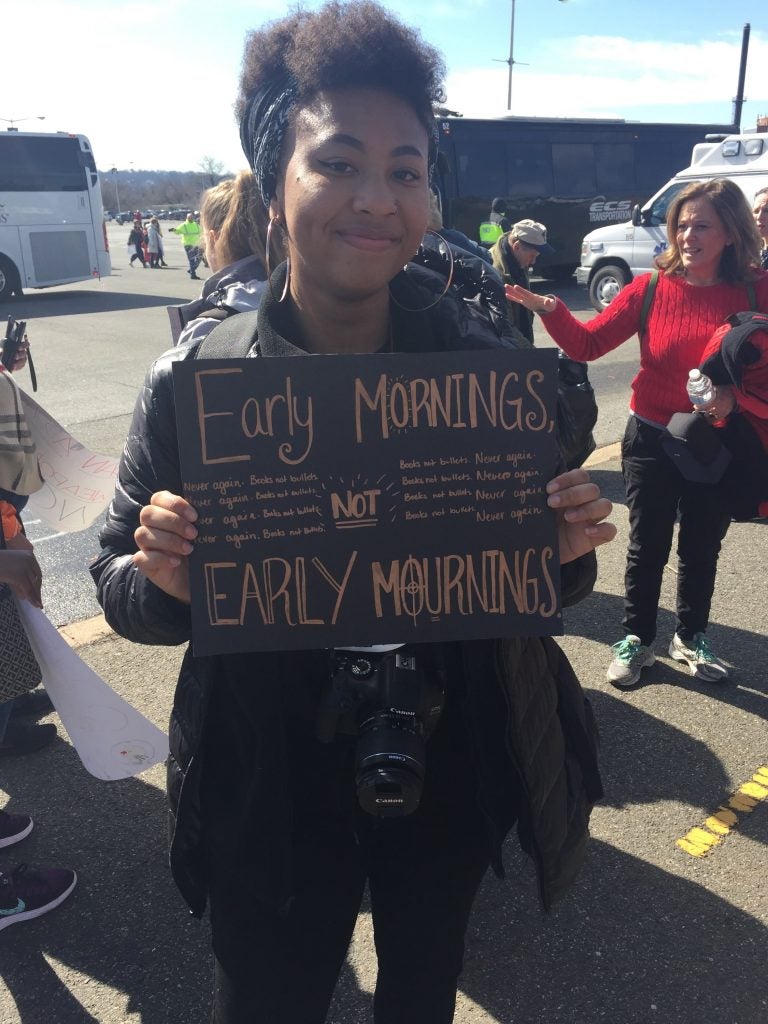

Santana Outlaw, 17, joined her classmates at Science Leadership Academy Beeber in West Philly on a bus trip to Washington, D.C. Saturday for her first national protest. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

As their chartered coach bus rolled toward Washington, D.C. on Saturday morning, about 30 students from Science Leadership Academy at Beeber in West Philadelphia got a pep talk from a veteran protester.

“It’s great to be here on the cool kids bus,” said Philadelphia Councilwoman Helen Gym.

Gym made her name as an education activist, a rabble rouser. Today, she told the students, she was passing the baton to them.

“We believe in you,” she said into the bus microphone. “We love you. We uplift you. Let’s go down to D.C. and make a ton of trouble.”

Almost all the students on the bus said they’d never been to a big, national rally before. Thanks to the nonprofit Public Citizens for Children and Youth, they were on their way to the March for Our Lives in D.C.

Saturday’s rally was framed as both a protest against gun violence and a galvanizing moment for teenage activists, led by the student survivors of the recent school shooting in Parkland, Florida. Fellow teenagers from around the country heeded their call, included many from Philadelphia.

“I’ve wanted to come a couple of times to D.C. for something like this,” said 17-year-old Santana Outlaw. “I saw the opportunity to do it for the March for Our Lives and I’m like, oh, let me hop on that.”

Outlaw jokes that people call her the Angela Davis of her school. She’s into politics and activism. She even started a club for kids to discuss social justice issues, but she’d never been to a D.C. protest.

Outlaw was ready. She wore an all-black outfit, accented with a black bandana and hoop earrings. Her backpack was stuffed with rally essentials, including a first-aid kit and hand sanitizer.

Outlaw first took an interest in activism after Trayvon Martin was shot and killed in Florida. He, like her, was young and black. His death struck a chord with her.

“It could be me,” she remembers thinking. “It could be my friends. It could be anybody that I know.”

Now, six years and several local protests later, she’d made it to her first massive demonstration.

“I feel like I’m going to cry,” she said. “If I do cry it’s OK. I have makeup wipes! But it’s definitely going to be life changing in a way. And I’m looking forward to that.”

You’d like to say that from here everything went smoothly, that lives changed, and people found their callings.

That’s not what happened.

After a confusing subway ride over to the rally site, the students surfaced to a chaotic scene. A bottleneck developed at 12th and Pennsylvania avenues, trapping the students in an eddy of increasingly frustrated protesters. For at least half an hour, they circled through the crowd, with only the muffled, distant sound of the rally to keep them company.

They started to lose patience.

“I’m so hot,” one of them bellowed.

The heat boiled over into an awkward confrontation with a woman trying to wheel a stroller through the crowd. She snapped at the students. They snapped back. It was hardly uplifting.

Finally, the kids nudged into a small clearing across from the Trump International Hotel. They couldn’t see the stage or even the jumbotrons. But they did hear singer Miley Cyrus’s rendition of “The Climb” and made the most of it — belting the words in an exaggerated, karaoke style.

Then, just an hour or so after they settled in, the students were told they had to leave.

With the rally that they still couldn’t see still going on somewhere near them, they headed back toward the subway. Santana Outlaw didn’t hide her disappointment.

“It was a lot crazier than I expected,” she said.

She lamented the fact that some of the people “seemed to be distracted,” more interested in the experience of marching and less interested in the issues.

“’It seems like you guys don’t care,” she said. “And obviously they kind of got under my skin.”

In particular, Outlaw had wanted to see Emma Gonzalez. The shave-headed, strong-willed survivor of the Parkland, Florida school shooting has become a rising star in the gun-control movement.

Eventually, Outlaw got what she came for, kind of.

As the students trudged back home, Outlaw saw on her phone that Gonzalez had taken the stage. In the middle of a dark and crowded subway station, she stopped and stared at a Facebook live stream.

The world swirled around her, but Outlaw was totally still, her face lit only by the light of her phone. It as if, for a moment, the chaos evaporated.

Santana stared at Emma. And Emma seemed to be staring right back.

“She is the voice that I always wanted to have,” Outlaw later said. “I feel like I’m looking in the mirror and I’m like wow that’s me up there even though it’s not actually me.”

It was a clarifying moment, and by the time bus turned back toward Philadelphia, Outlaw’s optimism had returned.

She grabbed the same bus microphone Gym had commandeered earlier in the day and shared her reflections with the bus.

“Emma Gonzalez is my queen,” she said half-jokingly.

Then she reminded her peers about the social activism club she’d started at school and how they were coordinating with a couple of other campuses on a potential event to mark the upcoming 19th anniversary of the school shooting at Columbine High School.

If Saturday proved anything, it is that are a lot of Emma Gonzalezes in the world.

At Science Leadership Academy Beeber, her name is Santana Outlaw. She didn’t have a perfect day on Saturday, but she saw something that made her want to keep marching forward.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.