Will Pennsylvania’s high court zap the rigged Republican map?

The practice of rigging congressional maps for extreme partisan advantage — known, of course, as gerrymandering — is under attack on a number of fronts.

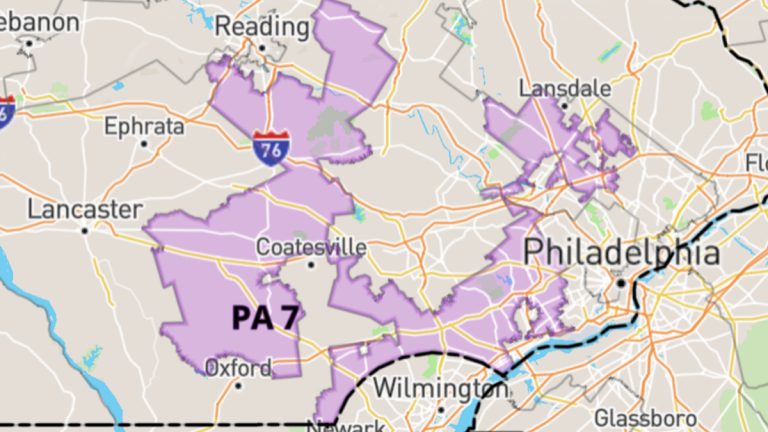

Pennsylvania's oddly-shaped 7th Congressional district is often cited as an extreme example of gerrymandering. (govtrack.us)

It’s tempting today to analyze the pillow-talk revelation that Donald Trump told porn star Stormy Daniels that she reminded him of his daughter, but I’ll focus instead on something far more substantive and arguably just as skeevy.

Because it’s indeed skeevy, in Pennsylvania’s congressional elections, that Republicans typically win only 50 percent (or less) of the aggregate statewide vote — yet they typically win 72 percent of the House seats, 13 of 18. No wonder election experts cite Pennsylvania as one of the most rigged states in the nation. No wonder the state’s highest court has been asked to get rid of the rigged system and make it fairer in time for the 2018 midterms. In fact, the seven supreme judges heard oral arguments about this yesterday.

The political stakes are high, because if the current congressional boundaries are erased — they were drawn by the majority Republican state lawmakers in Harrisburg to maximize likely Republican voters and disperse likely Democratic voters — any new, fairer map could make it easier for Pennsylvania Democrats to pick up some House seats in a year when they need to net only 24 seats nationwide in order to win the chamber.

And Pennsylvania aside, the practice of rigging congressional maps for extreme partisan advantage — known, of course, as gerrymandering — is under attack on a number of fronts. Last month, three federal appeals judges threw out the Republican-crafted map in North Carolina, ruling that the GOP’s rigging breached three provisions of the federal Constitution. Indeed, three of the nation’s most gerrymandered districts are in North Carolina. And last fall, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in a case that features Wisconsin rigging (by state Republicans) and Maryland rigging (by state Democrats), with a potentially historic ruling due later this year.

But here’s the problem: In most states, lawmakers in the majority party draw the boundaries, and typically do so for partisan advantage — clustering their most supportive voters, diluting their likeliest opposition voters, and winding up with squiggly geographic contortions. Judges have long been reluctant to rule on this practice, preferring to avoid what they’ve called “the political thicket.” On the other hand, computers have made map-rigging more extreme, so the key question for the courts is how much partisanship is too much partisanship — to the point of violating constitutional norms.

What’s noteworthy about the Pennsylvania case — brought by Philadelphia’s Public Interest Law Center, on behalf of the League of Women Voters and individuals in each of the 18 districts — is that the rigging may violate the strong language in the state constitution, which guarantees that “elections be free and equal; and no power, civil or military, shall at any time interfere to prevent the free exercise of the right of suffrage.” The plaintiffs’ legitimate complaint is that congressional elections aren’t free and equal when Republicans win roughly 50 percent of all House votes and wind up with 72 percent of the House seats. They rightly contend that this discriminates against Democratic voters.

And the most infamous example, of course, is Pennsylvania’s 7th congressional district, which is so geographically contorted that, depending on the eye of the beholder, it looks like a claw or Goofy kicking Donald Duck. A minuscule slice of the district literally runs through a restaurant parking lot in King of Prussia, so that habitual Republican voters on one side can be joined with habitual Republican voters on the other side. A slice of populous Montgomery County, which is packed with lots of suburban Democrats, is part of the 7th, but the county is also divvied up among four other districts.

Here’s how things should work: Voters should be able to choose their representatives; representatives should not be allowed to choose their voters.

The big question is whether the U.S. Supreme Court, in the Wisconsin and Maryland cases, will see it that way (or, to be more precise, whether swing voter Anthony Kennedy will see it that way); the same goes for Pennsylvania’s high court, where five of seven members are elected Democrats. How should they determine whether a partisan map is too partisan and thus a constitutional violation? (As Pennsylvania judge Max Baer, a Democrat, remarked at the hearing yesterday, “A test has eluded every court that’s grappled with it.”) If they kill the current maps and order new ones in time for the spring ’18 congressional primaries and autumn midterms, who draws the new maps and under what criteria?

Or since it’s the Democrats who have the biggest gripes, in Wisconsin as well as Pennsylvania, perhaps the best solution is for them to start winning state legislative races again, finding a way to end their long losing streak, so that they can control the congressional maps?

Courts, congressional boundaries, constitutions … heavy stuff. We could all use a break. Over to you, Stormy Daniels!

“He kept looking at me and then we ended up riding to another hole on the same golf cart together…”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.