Wide disparity in health, longevity within just a few miles in New Jersey

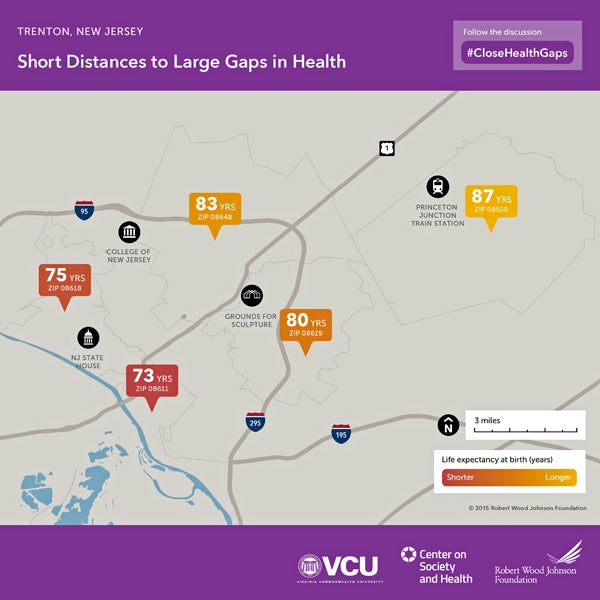

This map excerpt shows the life expectancy variations found in a new study paid for by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and conducted by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University.

What could you see — and do — if you had 16 years added to the end of your life?

Armed with a new study on life expectancy, community advocates are calling attention to a wide health gap across South Jersey.

If you live in parts of well-to-do Princeton, New Jersey, there’s a good chance you’ll live to age 87. But just down the road, for some residents of Trenton–where poverty is widespread–the life expectancy is as low as 71.

That’s one finding from a new study paid for by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and conducted by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University. The data was summarized in a map that shows an overall increase in life expectancy as the ZIP codes change to more suburban, wealthier areas. “What the maps show is there’s a limit to what can be done locally,” said Marty Johnson, CEO of Isles, Inc., an urban community development group. Narrowing health disparities requires a regional approach, he said, such as eliminating concentrations of poverty — so affordable housing is available in every ZIP code. “It’s not until we can really shove this in people’s faces — with a map — and begin to keep it in front of them in conversation that we’ll actually begin to see changes,” said Samuel Frisby, CEO of the Trenton YMCA. The city has added opportunities for outdoor exercise and nutritious food, and Frisby said those neighborhood changes could — someday — improve health across the community. A favorite new addition is the Greenwood Avenue Farmers’ Market where you can take a Zumba fitness class or get your blood pressure checked during one of the mobile health-screening events. “You have the opportunity for children to come and ride bikes in a closed-off area where they are safe,” Frisby said. “I actually live in the city, and our streets don’t have bike lanes here. What you will find is people will just ride their bikes up on the sidewalk, pushing pedestrian onto the grass.” “The work that we’ve done, policy wise, is pushing the lever in terms of educating people so they are doing things better. It’s not a long enough study to be able say, ‘Oh yeah, they are going to live 10 years longer,’” Frisby said. How long people live and how well they’ll live should not be predetermined by their ZIP code, he said. Derek Chapman, associate director for research at Virginia Commonwealth University’s Center on Society and Health, said there’s a new focus on the health benefits of community-wide improvements. “I think the conversation in the past has centered almost entirely on access to medical care and individual risk behaviors like diet and exercise and smoking and that sort of thing,” Chapman said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.