Why technology needs government

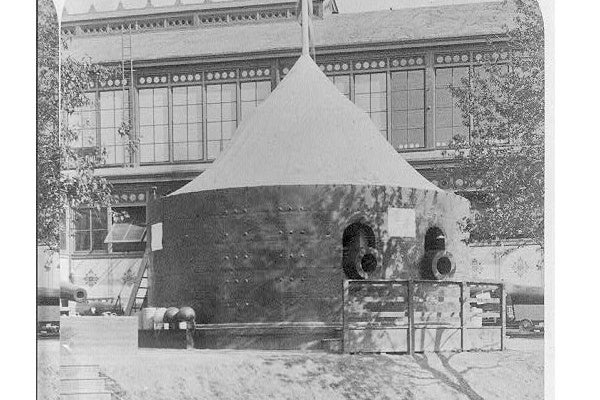

On May 10, 1876, President Ulysses S. Grant welcomed over 180,000 visitors to the opening day ceremonies of Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition in Fairmount Park. Grant turned a lever on the gigantic new Corliss engine, which powered the 800 other machines at the exposition.

With the first hiss of steam, viewers shouted and threw their hats into the air; guns roared, and churchbells pealed. The fair was officially opened, and Philadelphia had secured its place as the “Workshop of the World.”

I’d been thinking about this history as the city prepared for Philly Tech Week, which kicked off on Friday night with demos, contests, and parties. Since 2005, the region has added 6,400 jobs in high-tech industries. Meanwhile, traditional manufacturing jobs fell by 25,000.

That’s a net loss for Philadelphia, of course, but it isn’t really news. At the peak of its industrial boom, about 300,000 Philadelphians worked in manufacturing; today, just 52,000 do. And there’s no sign that tech jobs can make up the difference anytime soon.

So maybe we need to look again at what fueled the city’s early prosperity. Part of it came from Philadelphia’s location, perched on several key waterways and within easy distance of Pennsylvania’s bountiful farms and mines. The city also benefited from a steady supply of fresh immigrant labor.

But it got a big assist from government, too, in ways that we rarely recognize. And that might hold the key to reviving Philly’s moribund economy—including its high-tech sector—today.

For most of the 19th century, high tariffs protected young American industries from foreign competition. Meanwhile, state and local governments provided over $400 million —or $1.3 trillion in today’s dollars—to canals and railroads, which insured that other businesses could get their raw materials to factories and their finished products to market.

But that was chump change compared to federal aid, especially to the transcontinental railroad. The federal land grant to the Union Pacific Railroad alone was about the same size as New Jersey and New Hampshire combined. All told, the federal government ceded over 131 milion acres west of the Mississippi to the railroads. If all of those grants were concentrated in a single state, it would be the third biggest in the United States, behind Alaska and Texas.

During the Second World War, the federal government would also jump-start America’s high-tech industry. Here in Philadelphia, it funded the world’s first supercomputer, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator, which could measure the probable trajectory of missiles many thousand times faster than the human beings (also called “computers”) employed for that purpose.

After ENIAC, however, the government began to concentrate its high-tech contracts the the Sunbelt states of the South and West. It was especially generous to Stanford University, which partnered with private companies like Hewlett-Packard to establish an “industrial park” near its campus.

And so Silicon Valley was born. Despite our modern image of the lone maverick tinkering in his garage—think Bill Gates or Steve Jobs—the computer was a product of government dollars. But that money largely bypassed Philadelphia, which has been playing catch-up ever since.

One attempt was the establishment of “University City,” coined by planners in the early 1960s to attract high-tech companies. Adjacent to the University of Pennsylvania, the new district was Philadelphia’s answer to Stanford’s industrial park.

But it was much harder to create a high-tech district in an impoverished East Coast metropolis than in a bucolic California suburb. The growing minority communities of West Philadelphia objected to urban renewal plans for University City, which seemed like a way to wall them off from white professionals. And the professionals found it easier to relocate in Palo Alto—or in Austin, or in Seattle—than to brave the tense racial politics of the City of Brotherly Love.

So as we commemorate Philly Tech Week, and the energetic coterie of start-ups that are bringing new jobs to the area, we might also ask what Uncle Sam can do to help out. One set of answers lies in President Obama’s proposed tax deducations for high-tech companies as well as his plan to fund partnerships between universities and the private sector.

But in the long run, Philadelphia will need even more. We can’t attract the industries we want unless we have better schools to train their workers and improved infrastructure to move their products. And none of that will happen without huge infusions of federal and state dollars, which powered our last technological revolution. It’s time to invest in the next one.

That’s History is a partnership between WHYY NewsWorks and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Jonathan Zimmerman is an historian with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and teaches history and education at New York University. He is the author of “Small Wonder: The Little Red Schoolhouse in History and Memory” and is currently writing a history of sex education around the world.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.