Why racial disparities in asthma are an urban planning issue

African-Americans are three times more likely to die from asthma as whites.

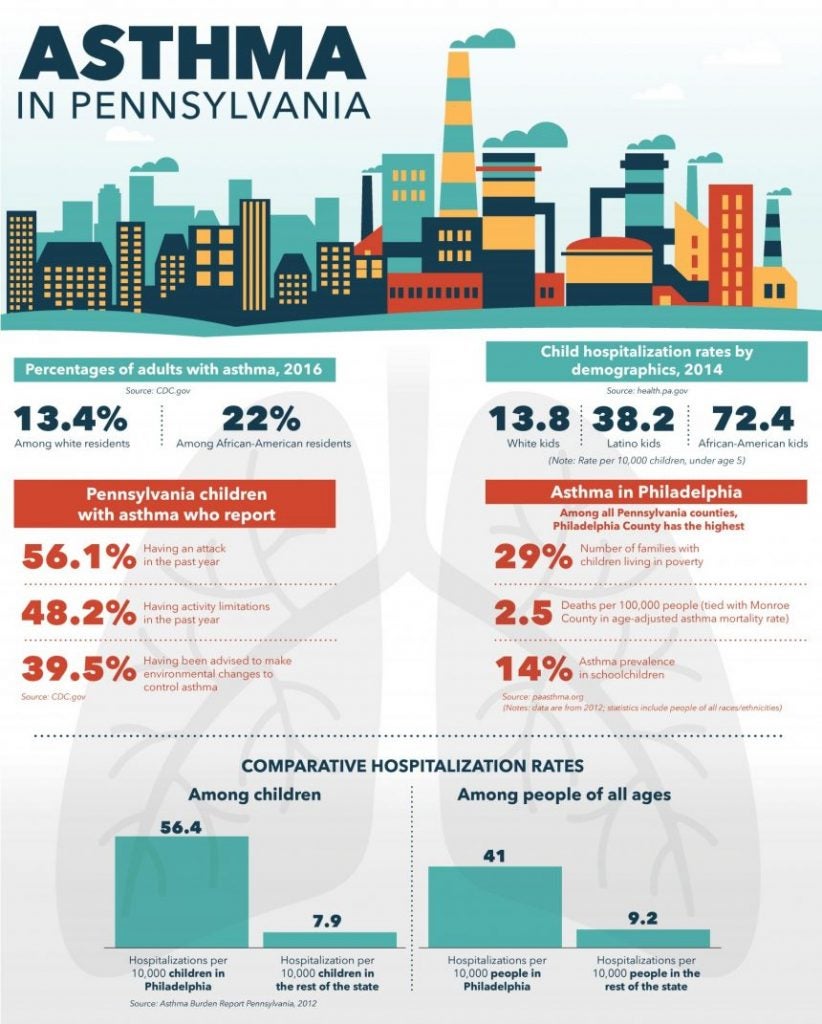

Philadelphia ranks #4 on the list of most challenging places to live with asthma in the U.S. Thirteen percent of the city's children suffer from the chronic condition. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

This story originally appeared on Next City.

“Every time she came in with one of her children, it was never a wellness visit,” Christian Banchs says solemnly. Banchs, a nurse, is describing one of his more memorable patients: a single mother with five children who would bring them all to his primary care clinic at the same time. “For her, it was more like crisis management than preventive care,” he explains, with a “child [who] really should have gone to the ER.” The crisis? “All of her children have asthma…. We were giving inhalers to five children although she had one appointment.”

It was a disease that Banchs, who lives and works in Philadelphia, saw often while providing pediatric nursing care. More than 26 million people in the U.S. have asthma, a condition involving spasms in the lungs that makes breathing difficult; it’s among the most common chronic diseases in the country. May is Asthma Awareness Month when public-health officials hope to increase education about the condition.

And asthma hits Philadelphia hard. The city ranks fourth-worst in the United States for asthma prevalence, and deaths from asthma occur at a greater rate in Philadelphia than anywhere else in the state of Pennsylvania. A disturbing 13 percent of the city’s children suffer from the disease.

The African-American community — a group that includes Banchs’s memorable family of patients — is particularly vulnerable. “African Americans make up a large percentage of the asthma population and are about three times more likely to have asthma, as well as to die from asthma, as whites are,” explains Ijeoma Kola, a doctoral researcher completing a dissertation on asthma in African Americans. The national statistics she cites reflect relatively mild disparities between white and African-American adults; but for African-American children, the rate of death from asthma is ten times higher than that of their white peers. Latinos face similar, although rather less stark, statistics.

But while effective individualized solutions exist, including medications and patient education, this approach cannot fully address the intense prevalence of asthma in communities of color. The pernicious legacy of institutional racism has segregated communities of color in underserved neighborhoods in cities across the country — districts with poor-quality housing stock clustered near areas of heavy industry, transportation centers and other sources of air pollution. What’s ultimately at the core of addressing asthma and its disparities, according to a wide range of researchers, activists, and public health professionals, is not attention to race itself at all. Rather, useful interventions range from clinical care to housing policy to confronting corporate and government polluters.

“This conversation is going to end up being very cyclical in nature,” warns Banchs. “Because one thing kind of affects another, which affects another, which affects another.”

Improved health literacy only goes so far

To hear Lily Higgins tell it, many asthma problems have to do with individual behavior. Higgins, a physician, works for the public health organization Amerihealth Caritas, which is one of several operating in Philadelphia. She describes her own frustrations at prescribing inhalers and medication delivery equipment, such as spacers and masks, to parents of asthmatic children. When she was working as a clinician, one concerned mother asked her, “‘Why is my baby not getting better?’” she says. “I said, ‘You know what, show your asthma medications to me. All your asthma medications, all the spacers — show me what you’re doing.’ And so she did, and she never took the cap off the inhaler. She didn’t know how to use the spacer and the mask [and] inhaler.”

This viewpoint — that improving health literacy is a key part of asthma care — underpins some of what Amerihealth Caritas now offers in Philadelphia. In 2014, the organization launched a program that provides inhalers and accompanying equipment to families in clinics, rather than via pharmacies, so that doctors can demonstrate their use.

Higgins says the program is useful, although she notes that much of Amerihealth Caritas’ efforts are pointed at another, more powerful target: preventing asthma attacks, rather than treating them.

This is an uncontroversial approach. Asthma involves spasms in the bronchi of the lungs, which causes bouts of wheezing and breathlessness. The disease is allergic in nature, with episodes typically occurring after the affected person comes into contact with specific triggers. A range of high-quality research studies — including several conducted in low-income communities of color — have established that asthma attacks can be significantly reduced through eliminating pollutants and triggers from an affected person’s home or environment; this includes dust mites, cockroaches, mold, tobacco smoke, rodents and/or air pollution.

Matthew Perzanowski, a Columbia University researcher, published a March 2019 article reviewing the current science. He notes that the more targeted the asthma care is, the more effective it can be: “A randomized controlled trial was done a number of years ago on a low-income urban population, and it was effective in reducing morbidity,” he says. “It was not just doing a blanket asthma intervention, but specifically testing children to see what they are allergic to, testing their homes to see what they were exposed to, and then targeting interventions” to the allergens present. Many other studies also advocate for an individualized approach.

While Amerihealth Caritas doesn’t carry out complex allergen testing, it does offer a form of individualized preventive care. The organization’s Asthma Navigators program employs community health workers to visit families with advice on managing asthma. “They do an at-home assessment of our members. That has major impact,” Higgins explains, providing education on common triggers and working with parents on eliminating them. She adds that navigators typically complete several follow-up visits per family.

When the air in your home makes your asthma worse

As with clinical care, however, this approach is known to be insufficient. Perzanowski explains the problem: “Often, the things that contribute to allergens in the home… are structural components that are hard to remediate. In other words, if someone lived in a low-income building, and they have cracks in the walls that are leading to cockroaches, then you need a landlord to remediate those cracks in the walls. So, sometimes residents aren’t able to do that.”

What does an Amerihealth Caritas Asthma Navigator do when a family’s asthma is triggered by housing problems they cannot fix themselves? Higgins says Amerihealth Caritas’ Asthma Navigators “will work with the individual member to help them navigate, to help them contact the landlord or the management company.” But she could give no further specifics.

Banchs, who also volunteers with the Philadelphia Tenants Union on housing issues, says that advice to call a landlord might not mean much at all. “When we [the Philadelphia Tenants Union] canvas apartment complexes, one of the biggest complaints is, you know, ‘I’ve had a leaky ceiling for years and my landlord has done nothing about it,’” he says. “It’s easy for us to say on the phone, ‘Yeah, get housing, get HUD [the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development] involved, get your landlord involved.’ But the mothers we talk to, the first thing is, a lot of them are housing-insecure. So, where they are living today, the next time we see their child, they’re going to be in a totally different situation.” Often, that instability means having little or no recourse when a dwelling triggers asthma.

Researcher Kola puts it more bluntly: “I don’t think individual management will effectively address the root causes of asthma. I think there needs to be housing reform.”

That’s a situation Philadelphia resident Izzy Jackson, a landlord with a grand mission, is well aware of. Citing an ongoing housing crisis in Philadelphia, she formed a limited liability corporation, Dwell City, to create 10,000 housing units for low-income Philadelphians by 2030. Her company, she says, hopes to bring a more personal, caring touch to low-income housing options. “So many things aren’t the responsibility of the tenant directly, that the landlord needs to be taking more seriously.” Jackson points to the distance between landlords and tenants as part of the problem she aims to solve. “I think in the city of Philadelphia, a lot of times, the problem is that the landlord is not as responsive, because it might be an LLC, it might be a landlord who does not reside in the city of Philadelphia, it might be represented by a large corporation or a property management company that is not as focused on tenant wellness.”

Banchs is acting, too. With the Philly Tenants Union, he’s worked to help get a local just-cause eviction ordinance passed that makes eviction illegal unless an appropriate reason exists. “Just-cause legislation is going to help people stay in their tenant-landlord relationships a little longer,” Banchs says, and deepening those connections can help give renters leverage to insist on repairs.

Perhaps most importantly, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation are working on a solution. CHOP operates the Community Asthma Prevention Program (CAPP), which received an award from the Environmental Protection Agency in May 2018 for excellence in asthma treatment and prevention. In a statement provided to Next City, the EPA said that the program, initiated in 1997, “equips families with asthma self-management education skills, in-home assessments for environmental asthma triggers, and connections to community-based resources to improve their child’s asthma… and has served more than 4,000 families and conducted approximately 20,000 home visits and performed primary care education for more than 21 medical practices.” Yet it, too, had offered no assistance for housing issues beyond tenants’ control. This past December, CHOP announced that it would address this shortcoming by engaging contractors to ameliorate asthma-provoking conditions in the homes of West Philadelphians. “Our community health workers actually go with the contractor and actually say, ‘Here’s a problem…’ from an asthma point of view,” CAPP director Tyra Bryant-Stephens explained to WHYY in December; this approach results in the completion of specified repairs paid for with program funding.

So far, however, these steps have been incremental. Banchs notes that new just-cause legislation only covers tenants with leases shorter than 12 months, which represents only a slim fraction of Philadelphia renters. Jackson has built just 2 housing units, a far cry from her 10,000-unit goal. The CHOP program is in a pilot phase, currently offering costly repairs to 10 carefully selected houses and planning to include just 100 houses in total.

What about the air out there?

Eric Marsh’s experience points out why addressing asthma from an individual housing perspective might also not be enough. The 48-year-old is a resident of Nicetown and involved with the Nicetown Community Development Corporation. Because he has a construction background and lives in a home a family member owns, he’s able to complete repairs on his own residence. Nonetheless, he says, moving back into the area from another neighborhood coincided with his elementary school-aged daughter developing asthma. “On a scale of 1 to 10, I’d say it’s a 7” in terms of severity, he says. “She hasn’t been hospitalized, but she’s been to the emergency room to receive breathing treatment for it.” Housing repairs alone have not resolved the problem.

Marsh has lived in Nicetown on and off over decades, so he’s aware of changes in the neighborhood. “When I was a kid… the streets were tree-lined,” he says, although now the area is much less green. Local housing stock has shifted from family-owned to renter-occupied, and many units are now decrepit. “Now there’s more traffic, there’s more residents, there’s more trash,” Marsh describes. “So, the overall environmental condition has decreased over time” — a situation that is known to cause neighborhood-wide surges in mold, cockroach infestations, and other factors that trigger asthma.

Correcting housing issues can only address indoor air quality, which is not the only source of asthma exacerbation in Philadelphia.

Nicetown is also home to Midvale station, a bus depot operated by the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) that has been central to the city’s public transportation system for the past 40 years. Marsh points out that it offers the neighborhood the advantage of adequate public transit service, but it comes at a cost: air pollution is intense in this area.

“Within the city, there are some very large sources of pollution, like the refinery and some other large smokestacks in the city, but then most of the pollution comes from local transportation,” Russell Zerbo explains. Zerbo’s job with the environmental justice department of the Clean Air Council is to focus on statewide, citywide, and local sources of pollution, with particular emphasis on protecting vulnerable low-income and nonwhite communities.

Zerbo points out that Nicetown is not the only area of Philadelphia affected in this way. He’s recently worked in Southwest Philly, where a convergence of auto-related businesses have heavily contaminated both the land and the air.

But Nicetown is an area of focus for many at present because over the past few years, SEPTA has steadily advanced a plan to add a natural gas-burning power plant to the Midvale bus depot. Residents fear it will worsen the already extensive air pollution; activists, including the national environmental group 350.org and the locally organized Neighbors Against the Gas Plant, have protested the plan since its announcement. “We’ve been going through the quasi-legal process of defending our appeal, and the city is defending the permit” to build the gas plant, 350.org organizer Mitch Chanin explains. The appeal has involved a lengthy series of hearings at the Philadelphia Department of Health’s Air Management Services; the final appeal hearing happened on April 30. The grounds for the appeal included concerns about health risks, not least of which is the exacerbation of an already-huge asthma burden. A review board will finalize a decision in late June; until the public comment period closes on May 30, 350.org and Neighbors Against the Gas Plant are continuing to ask residents to submit letters of concern to the city government.

The premise that outdoor air pollution aggravates asthma may be more controversial than any other in asthma care. In public testimony during the hearings, Arthur Frank, a physician and former member of the Pennsylvania Environmental Justice Advisory Board, noted that managing indoor air quality “seems to give one a better control of what happens to individuals than what goes on with outdoor air pollution.” Moreover, he noted, the connection between air pollution and asthma is not clear: “If you look, for example, at hospitalization by asthma rate, those parts of the city that have from general data the highest levels of air pollution do not have the highest levels of hospitalization for asthma.” In Nicetown, Frank claimed, data more clearly correlated asthma with smoking and poor housing than with air pollution.

Many point out that air pollution data is imperfect. Marsh and other residents worry over the lack of air-quality monitoring in the area, noting that the nearest air monitoring stations are 3 to 4 miles outside the neighborhood. Zerbo explains that this is by design; governmental air monitoring is meant to generate an average across the entire city, rather than drill down to neighborhood-specific numbers, which means most Philadelphia neighborhoods lack data on hyperlocal air pollution levels. Chanin and Zerbo both state that the air monitoring devices in use are not able to measure certain pollutants associated with asthma, leaving correlations between pollution and health outcomes incomplete and unclear. As a result, what the addition of a power plant will do to the neighborhood for people with asthma remains hard to quantify.

Banchs, who is a member of the Green Party alongside his other activism, points out that placing a power plant in Nicetown is offensive on principle: “When you look at these types of pollutants in the city, they are in poor, black neighborhoods. So that’s part of the social and racial justice component… that we fight [for] nationwide, but especially in Philadelphia.”

Way beyond genetics

One thing that appears not to drive racial disparities in asthma prevalence is race itself.

Other diseases are known to have genetic causes that strongly correlate to African heritage. (One, sickle cell anemia, served in mid-twentieth century America as both a key source of insight into the molecular biology of disease and a focus of community organizing by the Black Panther Party.) But genetic vulnerability to asthma seems less straightforward. Although overall susceptibility runs in families, and some studies have identified different genetic loci associated with the disease in people of different racial groups, simply being of a particular race or ethnicity is not an overarching biological cause of asthma.

Instead, the disparity seems to come down to socioeconomic disadvantage and the associated deprivation of an adequate standard of living. Kola, the doctoral candidate, say that a historical irony lies behind this. “Doctors in the 1890s believed that asthma wasn’t possible in black people, that black folks could not have asthma, because they conceptualized asthma as an elite, civilized disease,” she says. In other words, doctors believed asthma was found only among people of high socioeconomic status.

Although that belief was rooted in racial and medical ignorance, Kola says it was partially correct: asthma is often an urban phenomenon, and the African-American population, which at that point lived in predominantly rural locations, was relatively unaffected. “Due to the Great Migration, millions of African Americans moved from the rural south to the urban north from about 1910 to about 1950, to places like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia,” she explains. “That exposed a lot of African Americans to various environmental, housing, and social issues that we now know affect asthma.”

Being asthmatic isn’t necessarily about being African American. Rather, many African Americans living in Philadelphia and other U.S. cities can often endure poor living conditions, and asthma is often provoked by conditions of economic hardship. A range of elements causes asthma — from the microscopic (genes) to the scarcely visible (dust mites and other allergens) to the individual (clinical care) and, on larger scales, to one’s home, neighborhood and city. In turn, corporations and governments in those cities control quality-of-life issues such as air quality, transportation access and housing equity. In the end, the uniting factor is simple. Incidents of asthma correlate overwhelmingly to socioeconomic status.

Banchs says the memorable patient he described earlier fit this pattern, too. “The reason she came with all her kids is because she has no one to watch her children,” he says. “She has no one to watch her children because she can’t afford a babysitter. She can’t afford a babysitter because she can’t get a job, [and] she can’t get a job because she has a past [criminal] record.” He’s changed jobs, so he doesn’t know the current disposition of his former patients but says there is every reason to believe her five children remain asthmatic.

Viewed together, the many causes of asthma can make treatment and care seem impossibly complex. But the many levels on which asthma operates also mean that help can begin at any level, with effective improvements possible at every level. Similarly, racial and socioeconomic disparities could be ameliorated on multiple fronts. Essentially, all parties already share a clear understanding of the first step: that the intensified vulnerability of nonwhite communities warrants special care.

Nevertheless, “just thinking about it now is making me sad,” Banchs admits. “Because she’s just one person, and these problems are running rampant and have a very similar profile.”

This story was produced with support from Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. Next City is one of more than 20 news organizations in the collective. Follow us on Twitter @BrokeInPhilly.

This story was produced with support from Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. Next City is one of more than 20 news organizations in the collective. Follow us on Twitter @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.