Why did Mayor Kenney disable a tool for fighting blight in the name of ‘public safety’?

City Hall disabled the function after protesters showed up at the home of a top official. The change could impair efforts to improve neighborhoods.

A woman walks through a Philadelphia neighborhood. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Updated: 12:50 p.m. Wednesday

___

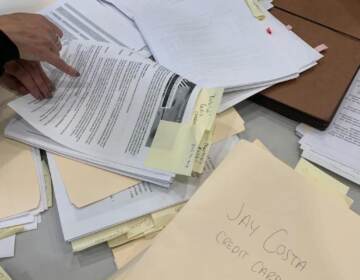

Philadelphia officials have intentionally disabled a feature allowing internet users to search city property records by name — a move that residents say will make it harder to fight blight in neighborhoods pocked by vacant and neglected property.

Mayor Jim Kenney’s administration removed the search feature some time in mid-September. In a call on Monday, administration representatives cited “public safety” concerns as their motivation in disabling the owner search feature on the Office of Property Assessment website, the main online portal for city property records. They declined to disclose the specific concerns or exact timing of the change, citing “security matters.”

Deputy Finance Director Cat Lamb said the move was meant to balance “public safety and transparency interests,” noting that users could still query individual properties by address and that property owner names were still searchable — albeit in a less convenient format — through the city’s bulk data portal.

“We thought disabling the search function would prevent ‘heat of the moment’ incidents that would target a property owner,” she said. “This is something we’ve been discussing for years.”

Most of Philadelphia’s neighboring counties allow users to search property records by name, while larger peer cities are split on allowing the feature. Asked why the city had made the change after years of consideration, she insisted that there had been “no specific incident” that motivated the change.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

However, public officials, like outgoing Managing Director Brian Abernathy were notably targeted by demonstrators at their homes over a summer that saw widespread civil unrest.

These incidents triggered a strong response from the city, which deployed counterterrorism detectives in response to the home visits. Lamb acknowledged that the “overall temperament of events right now” had contributed to the decision.

“It wasn’t a direct line from A to B, but I guess it’s maybe put the forefront in some of our minds about access to information and public safety,” she said.

But for residents like art consultant Rebecca O’Leary, the change feels like a step backward. She said she used the tool every day to research vacant or neglected properties that were attracting illegal dumping or criminal activity to her neighborhood. She used the database to connect the dots between houses where illegal activities were occurring or hazards going unfixed.

“I started to realize that many of the homes that are not occupied in South Philly are owned by the same families,” she said. “These are people who own houses in Newtown, Marlton, Cape May. These are people that inherited them or bought them as investment properties.”

University of Arizona associate professor David Cuillier, who is president of National Freedom of Information Coalition, said the decision was unlikely to improve public safety and far more likely to impact well-intentioned people like O’Leary.

“What they’re doing is misguided and it will cause more harm than good,” he said. “We know that when you make names searchable online via property records, it doesn’t lead to more crime or burglaries. There are anecdotes of course, but they’re very rare. You don’t set policy based on anecdotes.”

Cuillier said businesses, such as lawyers or real estate interests, comprised two-thirds of public records users on average. He said the city’s change was more likely to impact these businesses, residents like O’Leary, or community groups that used the tool for similar research.

“Identifying slumlords or big property owners is important,” he said. “You deserve to know who’s in your neighborhood and who owns all the properties around town. You need that name to do that.”

City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier described the change as a “net negative” in a Facebook post. “Community members are already out-leveraged when trying to negotiate neighborhood change (and neighborhood stagnation, in many cases),” the West Philadelphia official wrote. “The last thing we need to do is take information away from them, when it is quite literally the biggest tool that they have.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.