What you can do to reduce the global jellyfish explosion

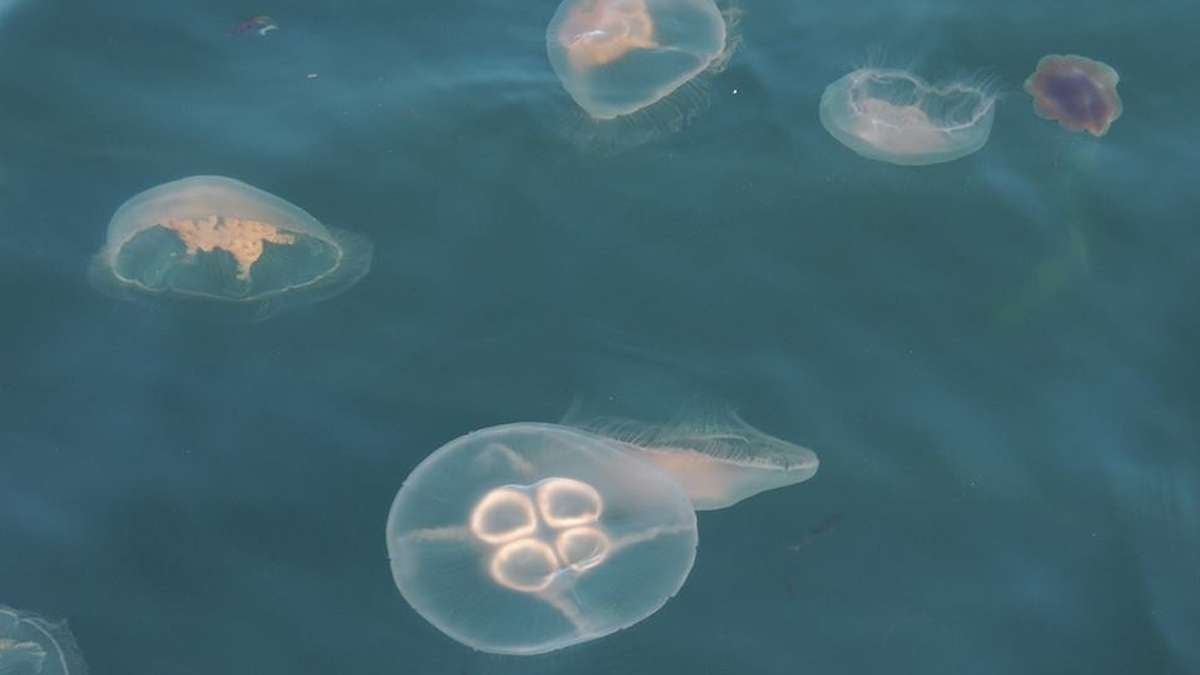

They ramp up the ick factor for tourists and can put a painful damper on a summer vacation, but the not-so-humble jellyfish carries a much more powerful sting – it’s waging guerilla warfare on the ocean’s ecosystem.

New Jersey is home to 15 species of jellyfish, and there is no way to forecast exactly how many of each will be pulsating through our waters this summer, since variables like current and weather are hard to predict. But as an overall trend, jellyfish blooms are increasing around the globe, thanks to human activities.

Sure, they’re an important part of the food web. But in excess numbers, these creatures create an imbalance in the environment, preying on fish populations until they collapse. They wreak havoc for the fishing industry by weighing down nets until boats are capsized, and they’ve been known to clog intake pipes at nuclear power plants around the world, crippling their output.

We’ve brought this problem on ourselves. The good news? There are things each of us can do to keep the tentacles in check.

Limit pollution

When we burn fossil fuel – say, by sitting in traffic on the Turnpike every Friday to get to the beach – we release nitrogen into the atmosphere. And when we apply chemical fertilizers to our lawns, nitrogen seeps into our groundwater. In each case, this nutrient eventually makes its way into the ocean, where it leeches oxygen and suffocates most marine life.

Jellyfish, however, thrive in this environment.

With fewer predators to cope with and less competition for food, these gelatinous blobs are able to reproduce at an alarming rate. In other words: “They’re fueled by our pollution,” said Paul Bologna, PhD, Director of the Marine Biology and Coastal Sciences program at Montclair State University.

In New Jersey, while water quality is generally considered excellent, the most recent report from the DEP indicates that nitrogen levels are on the rise, meaning jellyfish could be, too.

Since fossil fuels also contribute to higher ocean temperatures, the problem is compounded. Many fish require more breaths in warmer water, meaning they require more oxygen just as it becomes less available. When these fish die, the process of decomposition continues leeching oxygen, creating a vicious cycle. (Or a fortuitous cycle, if you’re a jellyfish.)

“Some people will tell you jellyfish blooms are simply cyclical,” Bologna said. “But denying the impact of climate change is like denying the Holocaust. The evidence is overwhelming.”

Protect the Predators

Few creatures can prey on jellyfish without succumbing to their venom. Swordfish, tuna and shark are among the exceptions. In order for these populations to thrive in New Jersey, it’s important that commercial and recreational fishermen abide by harvest quotas.

“There are systems in place at the state and federal levels to make sure the rules are followed,” said Larry Hajna, spokesman for the DEP. “We have conservation officers that patrol our coastline. But as with anything, there can be people who take more than they’re allotted.”

Every month, these conservation officers issue 315 enforcement actions for fishermen, hunters and others who violate the state’s wildlife laws. To reduce this number, the DEP distributes a free Fish and Wildlife Digest, available online and in sport retail locations, so that recreational fishermen can educate themselves on the regulations. Since 2010, they’ve also mandated recreational fishermen sign up with a Saltwater Registry, so that policymakers have an accurate accounting of how many fish are being taken.

Helping other jellyfish predators, like sea turtles, is often a matter of slowing down and paying attention. In 2015, Brigantine’s Marine Mammal Stranding Center responded to 36 loggerhead strandings, many of these due to boat strike. Loggerheads, while not yet endangered in most US habitats, are on the brink of extinction in New Jersey – another fortuitous situation for the jelly set.

Entanglement is also a primary threat, as evidenced by the 800-pound leatherback turtle that nearly got caught in fishing gear 30 miles off the coast of South Jersey in 2014. In this case, due to the call of a good Samaritan, Coast Guard crew from Cape May and Atlantic City were able to free the animal.

Scrub your deck

One type of Jersey Shore jellyfish, the sea nettle, does extremely well – they “grow like gangbusters,” according to Bologna — in lagoon areas where bulkheads and boat ramps provide ideal surfaces for polyps to latch and develop. Before so much development, these little bundles of baby jellyfish were limited to rocks on the seabed.

While Hurricane Sandy destroyed many of these structures and, therefore, reduced the jellyfish population for a time, rebuilding means sea nettle numbers are once again on the rise.

The underside of one floating dock can hold between 50,000 and 100,000 polyps. These little sacs then clone themselves, so that each polyp ends up accounting for approximately 2,500 jellies, or about 80,000 feet worth of stinging tentacle.

The Bulkhead Blitz program, launched in 2015 after a three-year research study led by Bologna, encourages homeowners to power wash or brush their bulkheads and decks at and below the high tide line every spring in order to disrupt the jellyfish lifecycle and restore some ecological balance. Experts also recommend removing boat ramps altogether when not in use.

Hold on to your shells

Just like decks and jet ski ramps are hospitable areas for sea nettle polyps, discarded oyster and clam shells provide an ideal space for latching. While it’s tempting to toss them into the water after a Memorial Day clam bake, resist the urge.

“They won’t help you start an oyster bed,” Bologna said. “But they will make it easier for sea nettles to proliferate.”

Keep an open mind

Jellyfish news – like last summer’s Portuguese Man O War scare, in which the dangerous, psychedelic-looking creature was found washed up from LBI to Stone Harbor – can make it easy to fear a hostile jellyfish takeover. But in the proper balance, jellyfish have their place. Some smaller fish will hide in the bell of a jellyfish for protection when a predator approaches, while some species of crab will climb aboard simply to hitch a ride. And their fluorescent proteins have been imperative to the biomedical field, contributing to both disease research and brain mapping.

The bottom line, according to Bologna: “Don’t let them scare you out of the water just yet.”

Related: Jellyfish explosion in Barnegat Bay worries scientists, Aug 5, 2011

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.