Honor legacies of Catto, King by protecting voting rights — and exercising that right

Pennsylvania's May 15 primary election is an excellent opportunity to cast your ballot.

An eager crowd surrounds the statue of Octavius Catto after its unveilling on the Southwest apron of City Hall. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The statue of Octavius Valentine Catto, 19th-century civil rights activist, gazes south from its perch outside Philadelphia City Hall. Mayor Jim Kenney, who as a councilman spearheaded the movement to recognize Catto with a memorial, often calls Catto “the Martin Luther King of his era.”

The comparison is apt. Catto led a successful movement to integrate Philadelphia streetcars in 1867. He also advocated passage of the 15th Amendment, granting suffrage to black men.

Sadly, the similarities also extend to the death of both men. Today, and every day, it is worth reflecting on Catto’s legacy, his untimely death, and what both of these leaders — gunned down before their time — can teach us about liberty, activism, and the ballot box.

Catto was killed at the age of 32 on Election Day 1871. This mayoral contest was among the first in which black men in Philadelphia were eligible to vote, as the 15th Amendment had been ratified just the previous year.

The candidate for the incumbent Democratic Party garnered widespread support among Philadelphia’s large population of unskilled Irish immigrants, many of whom had found jobs thanks to powerful political boss William “Squire” McMullen. As head of the Moyamensing Hose Company, a combination criminal gang and volunteer fire company, McMullen had a knack for transforming new arrivals into loyal Democratic voters.

African-Americans, however, were drawn to the Republican ticket — the “Party of Lincoln.” Understanding that newly enfranchised blacks could oust the Democrats from power, McMullen and his loyalists — some of whom were Philadelphia police officers — used violent intimidation tactics to keep black voters from the polls.

Beginning the night before the election and continuing throughout the day, black men were pulled out of line, beaten, and even shot. Rioting spread along the Lombard Street corridor, home to a large number of black residents. Catto, a leader of the black community, implored Mayor Daniel Fox for help, but he was turned away.

As a major in the Pennsylvania National Guard, Catto was ordered to report to the armory at Broad and Race streets to organize an end to the mayhem. He purchased a firearm at a Walnut Street pawnshop and then headed toward his boarding house at 814 South St. to retrieve ammunition. As he neared home, Catto passed one of McMullen’s henchmen. Frank Kelly, bandaged from an earlier encounter, turned on Catto and shot him — in broad daylight and in front of numerous witnesses.

We will never know if Kelly shot Catto because of who he was — a remarkable combination of activist, scholar, athlete, orator, vestryman, and teacher — or simply because it was Election Day, and he was a black man, one of six shot that day to scare away black voters in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to maintain Democratic control of the city.

Kelly fled the scene and crossed state lines, remaining on the lam for five years. When eventually extradited and tried, 28 eyewitnesses — African-American and white — identified Kelly as Catto’s assassin. Nonetheless, an all-white jury acquitted him.

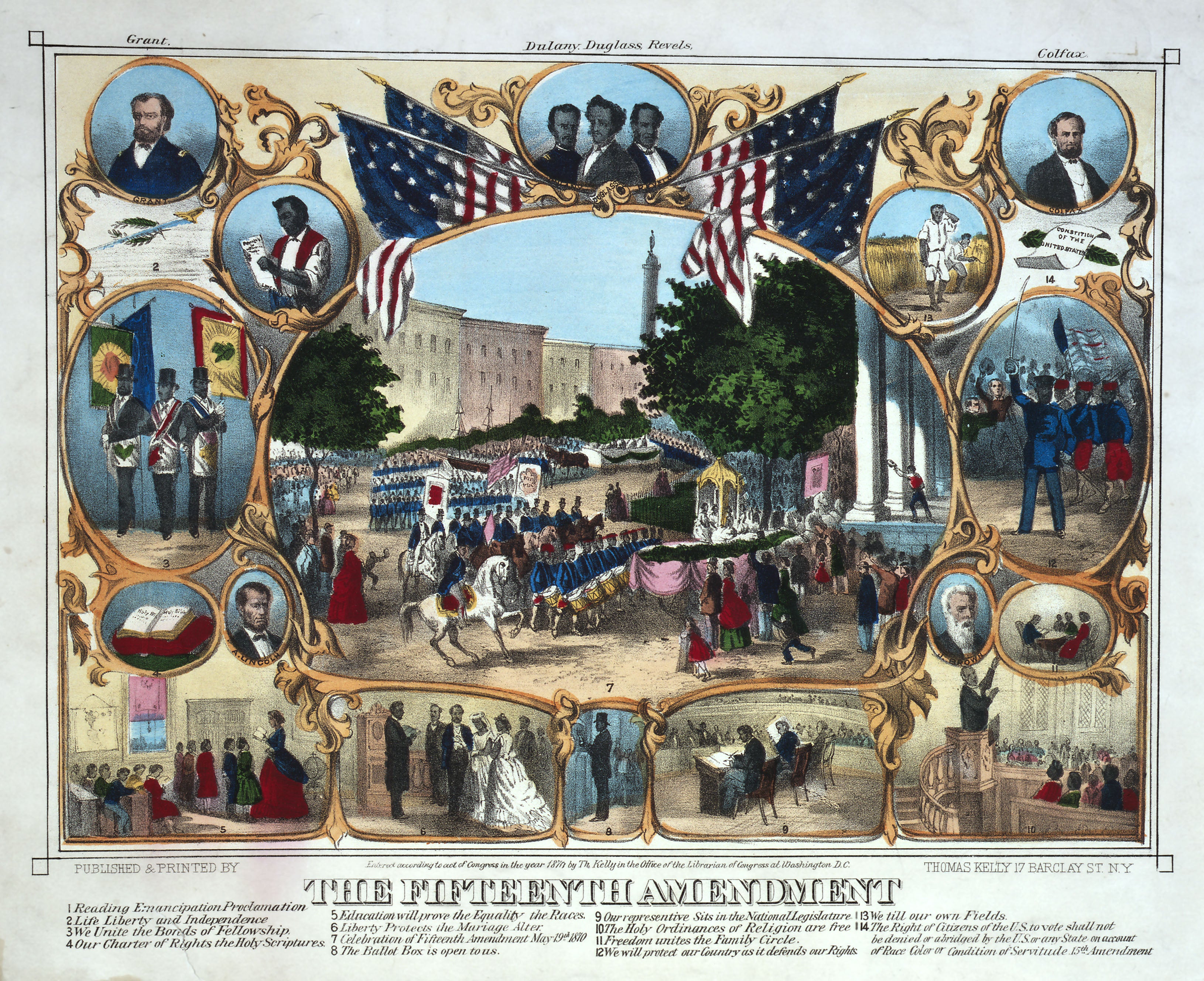

What do we learn from the murders of Catto and King? I think about a famous print depicting a Baltimore parade to celebrate ratification of the 15th Amendment. The central image is surrounded by small illustrations of scenarios expected to be realized after voting rights for blacks were established:

- Education will Prove the Equality of the Races.

- Our Representative Sits in the National Legislature.

- Freedom Unites the Family Circle.

These optimistic images of what suffrage could bring about should not be dismissed as naïve.

If voting — without violent intimidation, without literacy tests and poll taxes, without voter identification laws and gerrymandering — really were open to all, who knows how different our country might have been back then? Who knows how it might transform in the future?

Catto’s death deprived Philadelphia of its most notable civil rights leader at the time. Similarly, the assassination of King silenced the most prominent voice for full racial equality in 1960s America.

To honor both of their legacies, it is incumbent upon us to make voting as free and fair as possible by challenging partisan gerrymandering and discriminatory voter-ID laws. We should also show up at the polls every Election Day and cast our votes. Next week’s primary is a good time to start.

—

Amy Cohen is director of education for History Making Productions. She has produced a short film and biography of Octavius Catto.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.