Was N.J. ‘betting on wrong horse’ in giving Holtec $260M tax break for Camden move?

Listen 5:40

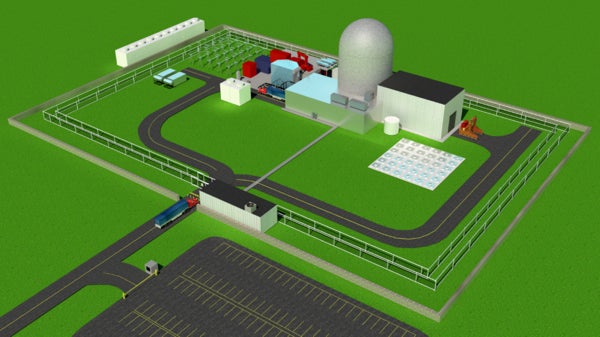

Government officials attend a ceremony for the raising of the final steel beam at Holtec International. The company got $260 million in tax incentives to build its manufacturing plant in Camden. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

When energy company Holtec International won a tax credit in 2014 to move to Camden, boosters applauded a new era of manufacturing in a city with a long history of blue-collar jobs.

At the time, little scrutiny was focused on what would become the centerpiece of Holtec’s factory operations there — a small nuclear reactor billed as cheaper and safer than its hulking predecessors. (They won’t actually be operating any nuclear reactors in Camden, just building their parts.)

But now critics in the energy industry are questioning whether any customers will want to buy the new reactor and, as a result, whether Holtec will be able to make good on its pledge to create hundreds of new jobs.

“They might hire a bunch of people … for a little bit and then, after a couple of years, fire them,” said M.V. Ramana, a researcher at Princeton University, who studies the global nuclear power industry. “I think that’s the best scenario you can expect.”

Camden residents, all too familiar with corporate promises of work opportunities that do not pan out, are also asking whether these are the kinds of jobs the city even needs.

Nuclear fizzle?

Small modular reactors — known as SMRs — are still a relatively new concept in the nuclear energy industry. They are so new that not one of the U.S. companies designing them, including Holtec, has actually built a single one.

But proponents say SMRs are the future of nuclear energy.

“A lot of very large players were looking at this question of small modular reactors,” said Mark Cooper, a senior fellow for economic analysis at the Vermont Law School, who researches the nuclear industry. “It’s pretty clear to everybody that the large reactors are a dying business.”

Manufacturers claim that the new, small reactors would solve two of the main problems with traditional, large reactors: cost and safety. They say SMRs would require less money to build and could be constructed mostly off-site, and the technology would reduce some of the safety concerns of a post-Fukushima world.

But some experts in the energy sector contend that SMRs are not a panacea to the nuclear energy industry’s problems at all.

Critics say claims that SMRs will cost less and be safer are overblown, and that renewable energy sources like wind and solar have become cheaper than ever to produce and are attracting record investments.

As a result, they ask, who would be willing to shell out for the fledgling technology of small modular nuclear reactors?

“From the point of view of the economics of low-carbon electricity, SMRs are not very attractive,” said Cooper.

But Holtec has confidence in its product. In its application to the state Economic Development Authority for a tax break to move to Camden, which WHYY obtained through a public records request, Holtec predicted a “trillion-dollar market beckoning for SMRs over the next 25 years” and claimed that “Holtec is at the forefront in this high-stakes global race.”

Holtec vice president Tom Marcille dispelled criticism that it was presumptuous for Holtec to build a brand-new factory in Camden dedicated specifically to its small reactor, the SMR-160, when the demand for the technology is still in question.

“One of the things that you have to recognize from the history of industrialized America is those people and those industrial founders who’ve had a vision and a belief in something have made commitments at an earlier and faster pace than those around them,” said Marcille, who runs the company’s small modular reactor division.

“Anybody who’s talking about delivering an SMR power plant in the 2020s who doesn’t have a factory today, or who isn’t building a factory today, is late to the game.”

Tax break

Two years ago, Holtec received a $260 million tax break over 10 years to build its new factory in Camden.

It was part of a controversial program run by the EDA called Grow NJ, which gives companies considering leaving the state tax credits to keep jobs in New Jersey.

Since lawmakers revamped Grow NJ in 2013, the state has approved more than $4 billion in tax credits for companies making a capital investment and keeping or creating jobs in New Jersey, according to the EDA.

As part of the state’s deal with Holtec, the company vowed to build a new factory, move 160 current employees from Marlton to Camden, and create another 250 jobs at the new site.

Company officials have gone even further than that, claiming that the new Holtec Technology Campus could employ 1,000 people by the end of the decade and up to 10,000 people by 2030.

And Holtec said it has history on its side: At a recent event at the Camden site, president Kris Singh assured officials that the company has never laid off an employee for lack of work in its 30-year history.

So far, though, Holtec has no definite buyers for its SMR-160.

“Half a dozen” clients have indicated with a “soft yes” that they are interested in buying the SMR-160, according to Marcille, who said that that is typical of early-stage agreements in the energy industry. (He would not name the clients but said they were all international.)

Yet in its Grow NJ application, which won Holtec the $260 million tax break, the company described one such commitment in stronger terms. The company said that New Jersey-based energy company PSE&G had a “long term interest of installing the efficient and environmentally friendly Holtec SMR-160s at its South Jersey site,” where the company already has two nuclear reactors. (Although PSE&G’s name was redacted from the application provided to WHYY, a spokesman agreed that it referred to the energy company.)

In fact, PSE&G has not even said publicly whether it will construct a new nuclear reactor in South Jersey, let alone install a small modular reactor or specifically the SMR-160.

“We have no immediate plans to build a new plant at this time,” said Joe Delmar, a spokesman for PSEG Power, the company’s nuclear division. “We have not chosen a reactor technology, and the SMR is one option that would possibly be considered if and when we were to pursue construction.”

According to Ramana, the Princeton professor, New Jersey “bet on the wrong horse” when it passed up a potential $260 million in tax revenue to keep Holtec from leaving the state.

“When they decided to invest in this, they decided not to invest in offshore wind projects,” he noted as an example. “I think the state of New Jersey could have invested in a whole bunch of other things.”

The tax break to move to Camden was not the first time Holtec sought government funding to bolster its SMR-160 program either.

In 2012, the U.S. Department of Energy offered multimillion-dollar grants to companies developing small reactors, hoping that the cash injection would spur private investment in the early-stage technology.

Two of four applicants were chosen. Holtec was not one of them.

In any case, “that factory will by no means sit idle or be a loss,” said Marcille. If the bet on the SMR-160 does not pan out as Holtec is hoping, he said, the Camden site can be used to build other products made by the company.

Impact on Camden

Part of the Grow NJ program is aimed at creating new jobs in Camden and other distressed cities.

While Holtec’s tax break does not force the company to hire Camden residents, officials have promised to do what they can to employ city residents.

Kelly Francis, Camden resident and president of the local chapter of the NAACP, welcomed the opportunity for local residents. But he said that even if the jobs at Holtec do materialize, they are not the types of jobs needed in Camden, a city of mostly low-skilled workers.

“We need entry-level jobs, like what got me my start at Campbell’s Soup,” said Francis, who loaded food onto freight cars to pay for college. “That’s what you need to get started in life. That’s what these young people in the city of Camden need.”

A recent survey from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia agreed with Francis. Companies and organizations that responded to the survey claimed that offering tax breaks to high-tech firms like Holtec leaves little funding for New Jersey companies that would hire a larger number of entry-level workers.

“The economic development planning and allocation of incentives are targeting firms with jobs that require advanced degrees,” states the report. “This lack of alignment with available workforce will leave few parcels of land available for the development of firms with entry level, low-skilled labor jobs.”

Holtec has attempted to address this issue by setting up training programs to help city residents improve their technical skills and become better qualified for jobs at the company.

In June, for example, a free training program for welders at Camden County College graduated its first class of nine students, who hailed from Camden City and other parts of South Jersey.

“We’re working hard to hire Camden residents and Camden County people,” said Lee Laurendeau, Holtec’s director of manufacturing. “Walking the talk.”

But Francis said he has seen companies guarantee jobs for Camden residents before, such as the Adventure Aquarium and the entertainment venue now known as the BB&T Pavilion.

“The only people I see working there are suburbanites,” he said, “but these are the promises they make in order to get a foothold.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.