Why your neighborhood school probably doesn’t have a playground

Research shows kids benefit from playgrounds, but 2/3 of Philadelphia public elementary schools don’t have playgrounds. To build them, schools are relying on private funders.

It was the shortest day of the year: the winter solstice. And, more importantly for Maurice and McKenzie Barnes, the evening was warm enough to play outside. They were in high spirits as their mom picked them up from after-school care at James R. Lowell Elementary in Olney, where 9-year-old Maurice is in fourth grade and McKenzie is in first.

It’s a short trip home — the family lives right across the street from the Philadelphia school — so even though it was dark, the kids’ mom, Shante Barnes, let them stay out for a little while. She even joined in, tossing a football with Maurice in the schoolyard. McKenzie and the littlest sister in the family, Ma’Leiyah, ran around on a delivery ramp alongside the building.

Lowell administrators call the fenced-in area surrounding the building a schoolyard, but it doubles as the parking lot. As the kids played, teachers got in their cars and pulled out for the evening.

The kids’ grandmother, Antoinette Reynolds, kept an eye on them from the family’s front porch, her usual lookout point. Reynolds, who describes herself as a “nosy neighbor,” often watches the action in the concrete square, especially before and after school, when young people gather.

“You’ll usually hear me yelling, ‘Hey, don’t do that! Get off of that! Don’t touch that, go back in the schoolyard,’ ” Reynolds said, and laughed.

Ma’Leiyah is a toddler in the truest sense of the word, and as McKenzie chased her up and down the delivery ramp, a face plant into the concrete seemed all but inevitable. Reynolds cringed as Maurice dove for a long throw, taking a spill onto the asphalt.

“All it takes is one fall,” Reynolds said, shaking her head. “And you know, hope for God it won’t be nobody’s head.”

Lowell is among the two-thirds of Philadelphia School District elementary schools that don’t have playgrounds. At these public schools, students run around on cracked pavement, among parked cars and between dumpsters.

From Thomas G. Morton Elementary School in South Philadelphia to James Dobson Elementary in Manayunk, kids spend their daily outdoor time on these often barren yards.

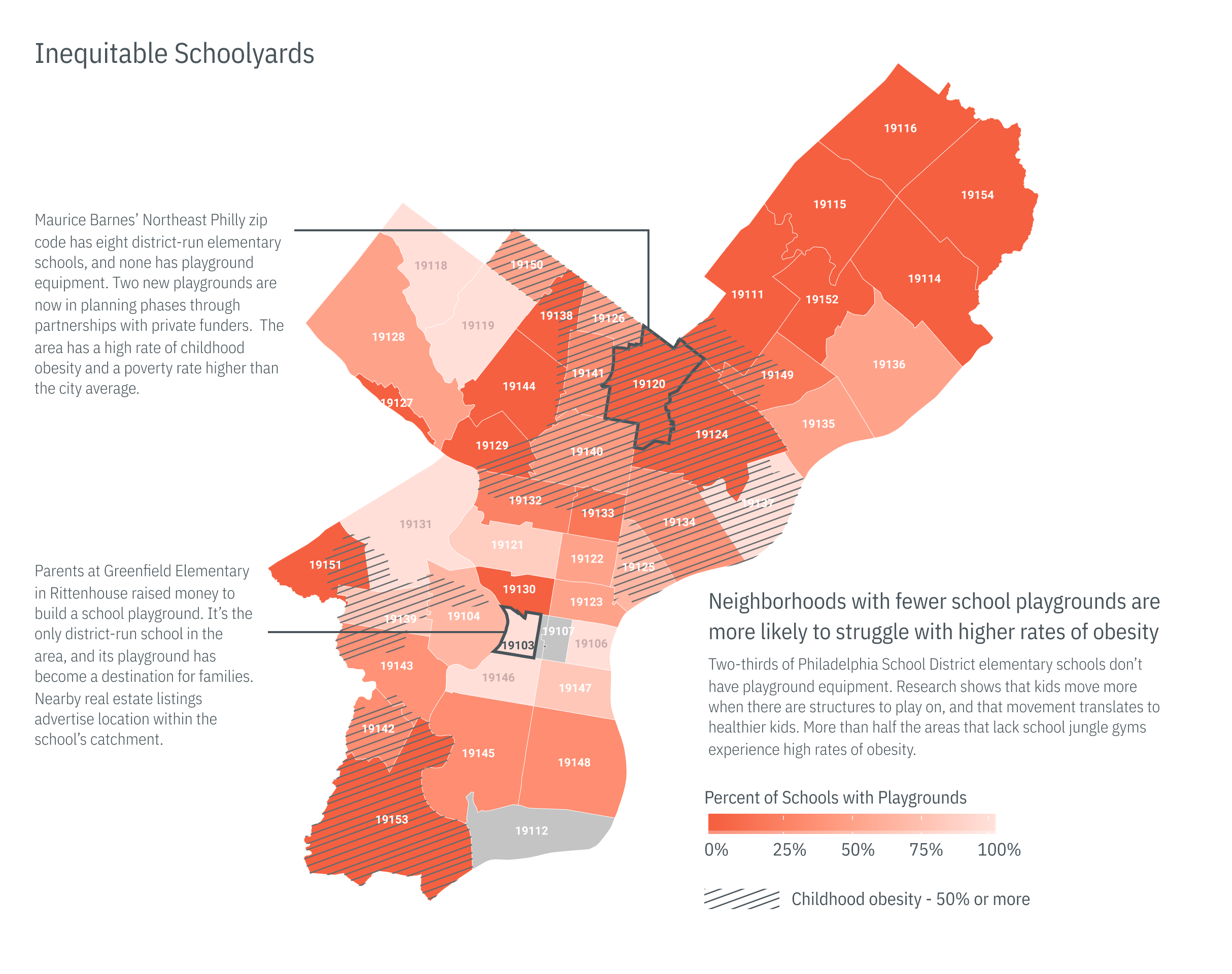

A map of the district’s play structures reveals distinct patterns. Playgrounds are more common in Center City and neighborhoods closer to downtown. Gentrifying neighborhoods and those with a strong history of community-based activism and development are more likely to have them.

The monkey bars and jungle gyms commonplace at suburban schools tend to be missing in neighborhoods with high rates of concentrated poverty, and areas with the fewest playgrounds tend to be areas predominantly home to communities of color.

The 19120 zip code, where the Barnes family lives, has a poverty rate of more than 30 percent, higher than the Philadelphia city average. About half the residents there are black, a third Latino, 15 percent Asian. None of the eight elementary schools in the zip code has a playground. It’s a problem that contributes to the other challenges these underfunded schools face in educating students, said David Lugo, Lowell’s principal.

“[Playgrounds] develop their gross motor skills, their fine motor skills,” said Lugo. “The space is there, but there is no equipment. There is nothing for them to get engaged [with] and to develop those different areas.”

There is no substantial line item in the Philadelphia School District’s annual budget to support playgrounds. Instead, a piecemeal system of public-private partnerships funds the handful of schoolyard-improvement projects that move forward every year. It’s a strategy incapable of addressing many of the inequalities baked into the cash-strapped system, but for now, it’s all the district has.

Yet a growing body of research points to the value of play in child health. Schoolyard space is an efficient and even-handed way to boost kids’ health because kids are at school each day, no matter their socioeconomic status, said Sharon Danks, Founder and CEO of Green Schoolyards America. She has come to believe that these often overlooked scraps of public land are key to creating healthier communities.

“If we are able to shift the environments at school, then the number of hours kids get to spend in nature increases and it becomes a lot more equitable,” Danks said.

If schoolyards were approached more like parks, we’d all fare better, she said.

“Our school grounds are parks that are hugely used, and they have not been invested in to a degree that reflects their user rate,” Danks said. “Children don’t vote directly, and their voices haven’t been heard.”

Good for recess, and real estate

Every year, the School District of Philadelphia puts out a budget call for schools to submit a sort of wish list: for building improvements, new paint jobs, and, of course, playgrounds.

“I’m sure it will come as no surprise to you: [Playgrounds] are one of the most heavily requested items that we get from schools,” said Danielle Floyd, the district’s chief operating officer.

Of the 180 elementary schools, Floyd said, about half ask for playgrounds each year.

But there is no formal process for what to do when that happens, because there’s almost no money in the district budget for playground construction. The school district has $1.5 million set aside for all stormwater, greening and playground improvements each year — in many cases, that can be the cost of improvements to a single playground.

Without a dedicated budget for schoolyards, Floyd said, the school system counts on partnerships to manage playground projects and fund them.

“When you have so many schools, that can only give you so much bandwidth,” she said.

The district has found help in the philanthropic community and from friends-of groups associated with certain public schools. When an outside group comes to the district with a plan and some money it has raised to build a playground, the district kicks in an average of $175,000. All said and done, the design and build process usually takes a few years and costs about $800,000.

Floyd estimated that the district completes eight to 10 playgrounds each year, most of them with private dollars.

One of those projects was at Chester Arthur Elementary in the Graduate Hospital neighborhood. The William Penn Foundation gave $1.1 million to a friends-of group there to transform the parking lot outside the school into a playground with outdoor learning elements. They built a giant, spider-like rope structure that sits atop an absorbent surface. A simple sundial is painted on the basketball court, so the kids can use the shadow of their own bodies to tell the time, depending on the season.

Mike Burlando co-chairs the playground committee within the Friends of Chester Arthur. He said the playground project was one of the rare occasions when the group took on a project that was not necessarily the first priority of the school administration. As those parents saw it, a symbol outside the school would deliver a message to families new to Graduate Hospital — one of the fastest gentrifying neighborhoods in the city — who might otherwise send their kids to private school.

“Getting people to the school is the first part of getting them into the school,” said Burlando, who can walk there from his house with his 2-year-old and 4-year-old. “Almost from a marketing — and just having a good face on the school — it was a real priority.”

Burlando’s kids aren’t old enough to go to Chester Arthur yet. The same is true for many of his fellow volunteers in the friends-of group. For them, building a playground is an investment.

Greenfield Elementary in Rittenhouse Square is home to another landscaped play space that’s open to the public. It’s considered an amenity not only for the school, but for the neighborhood. Parents there are using the schoolyard as a way to raise funds from neighborhood residents who don’t have kids at the school, yet recognize the value of community green space in dense urban areas. The argument hinges, in part, on research that shows green space can increase property values in a neighborhood. That’s an easy sell to developers, too.

“In their brochures, when they want to sell condos that overlook it or are a block away, they can say, `Look at this amazing playground that’s two blocks from your new apartment,’ ” said DeWitt Brown, a Greenfield parent who heads fundraising.

Their organization has already received support from Alterra Property Group, which develops many buildings nearby.

Playgrounds can act as a sort of leveraging tool, too. Back in 2009, a developer wanted a zoning variance to build a 34-story apartment building at 2116 Chestnut St., near Greenfield Elementary. The Center City Residents’ Association negotiated to get the developer to contribute to the school’s playground-maintenance fund in exchange for support for the variance. That $50,000 helped cover the costs of the additional wear and tear new residents would bring to the outdoor space. More than that, it was an act of goodwill.

But most neighborhoods don’t have developers willing to drop $50,000 to prove their neighborliness. Not Olney, where developers aren’t building condos and Lugo searched for years for donors to help him build a playground. The Lowell Elementary School principal was a physical-education teacher before he moved into administration, so he places a higher premium on recess than other school leaders might. No matter how earnest his pleas, he wasn’t able to find local financial support.

Lugo’s fundraising struggles don’t surprise Floyd. She said that when the school district takes the lead on a playground renovation, it aims to focus on schools in poorer areas, with higher percentages of students on free- or reduced-cost lunch programs. More often than not, however, it’s the communities with more resources that come to the district, understanding they must bring their own money to the table.

“We have found more-affluent areas to actually approach us and say, ‘Hey, we’ve raised all this money, when do we get this done? How do we work with you, how do we partner with you on it?’ ” Floyd said.

The district simply doesn’t have the money to do it any other way, she said. A landscape architect on staff ushers its small portfolio of playground projects forward, and manages those brought by outside groups.

“As a department and as a district, we have to be flexible in terms of supporting both ways,” she said.

And, some might argue, maybe that’s enough. In a cash-strapped district, where kids need new textbooks, buildings need upkeep, and teachers need to be paid, should a jungle gym really be the priority?

‘We were very lucky’

In Philadelphia, 20 percent of children are obese. A large body of research shows that access to green spaces increases kids’ physical activity and helps reduce their weight. There is less evidence linking school playgrounds specifically to a bump in physical activity, but that research is growing.

Natalie Colabianchi is the chair of applied exercise science in the School of Kinesiology at the University of Michigan. She led a study in Cleveland comparing playgrounds with old or no equipment to renovated playgrounds. Not only did the researchers find that there was more physical activity on the renovated playgrounds, they also found that the more things to do — sports fields, play structures, swing sets — the higher the utilization. Other studies have found that kids are more active on play structures and grassy spaces than on concrete or paved areas.

“Having play equipment is associated with higher physical-activity levels,” said Colabianchi. “And I think some people would probably think, ‘Well sure, of course!’ But then, there are some schools out there that don’t really have play equipment.”

The benefits of adding green space to a neighborhood go beyond increased activity for kids. Many of the health benefits are behavioral and environmental. Studies have found that students with views of trees from their classrooms increase focus and reduce stress. Depaving or using “cool pavements” can cool down urban heat islands, which have a variety of negative health outcomes, ranging from contributing to greenhouse-gas emissions to increasing risk for heat stroke among kids playing in the summer months. Adding trees can improve air quality.

Such environmental benefits have not gone unnoticed. In fact, stormwater management has become the principal driver for public funding of playground renovations in Philadelphia.

The Philadelphia Water Department has a stake in playgrounds because it recognizes the opportunity to manage the stormwater on public land, preventing runoff and pollution of the area’s water supply.

Greenfield Elementary School parents identified this potential back in 2007, and appealed to the Water Department for funding. Their resourcefulness was born of desperation: A year before, the district had selected the school to receive a $100,000 grant for playground renovations, but the funding fell through when the district ended the program due to budget constraints. Luckily, they were prepared: Parents from the school had spent a year working with the Community Design Collaborative, which helps community groups draw up designs at low cost.

Lisa Armstrong was a parent at Greenfield for 23 years and was involved in the playground project from the beginning. When the district’s funding dried up, she said, they had a decision to make.

“We had a road map to follow, so when we lost our hundred thousand, we just knuckled down and decided we were gonna take up the challenge,” Armstrong recalled.

The parents organization found a list of area foundations and their funding priorities. Members met every other week, as a group of 16 broken up into teams of two.

“We had all sorts of parents with different skills who helped us really fine-tune,” said Armstrong. She and her husband are architects by trade. Other parents were lawyers, writers and masons.

One parent even built an apple press. The schoolyard has an area for edible plants. And, when the apple trees fruit in the fall, the students use the press to make cider. Over the years, the press itself has become a source of income for the playground. Parents use it to make hard cider they can sell at an annual silent auction to raise money for the schoolyard.

“We were very lucky,” said Armstrong.

Greenfield is the only school in the 19103 zip code, but its playground has become a model in design and fundraising citywide. Over the years, Greenfield raised more than $800,000 for its schoolyard. And it all started with the grant from the Water Department, which used Greenfield as a prototype for playground improvements that incorporate stormwater-management infrastructure at schools all over the city.

If that process seems a little backwards, it’s because it is, said Beth Miller, executive director of the Community Design Collaborative.

“There is no one city leader spearheading the process,” said Miller. Over the years, she said, her group learned to omit elements in plans for schools that she knew the district didn’t want.

“But there’s no master list for that,” said Miller. “We’ve just figured it out from years of working together.”

The Community Design Collaborative has made master plans or designs for at least 18 schoolyards. But not all those plans have been realized.

Despite the best efforts of the district to shepherd the process, she said, not every school community has a network of parents able to organize and raise funds at the level needed for a project to succeed. Miller said the design collaborative is moving away from taking on schoolyard design projects, in part because of the uphill battle in many Philadelphia communities.

“We’re creating a lot of demand on their limited resources,” she said of the district.

Ideally, Miller said, there would be a streamlined system that began with designers and flowed through to project managers. But as it stands, she said, there are only a handful of those project managers, and they’re at capacity.

The Trust for Public Land, a national nonprofit that aims to increase access to green space, is one such project manager. Historically, its focus in cities has been to bring residents within a 10-minute walk of green spaces. Once the trust started thinking of schools as parks, it made sense to invest in them.

“If you’re looking to make an investment in a place that people recognize and see as `theirs’ schoolyards are a tremendously strong choice,” said Owen Franklin, Pennsylvania state director for the trust.

Sharon Danks, the environmental planner who advocates for green schoolyards, thinks that mindset is key for getting public investment into playgrounds. The way she sees it, kids spend the majority of their time at school already, so not investing in schoolyards is a missed opportunity.

“I think of it as our most densely inhabited park space, but the infrastructure hasn’t been developed with that perspective,” Danks said. “It is our most well-used public parkland, completely undeveloped.”

The Trust for Public Land has completed a dozen schoolyards in Philadelphia and South Jersey. It doesn’t have a formal set of criteria for how it chooses which schools to work with, but Franklin said it comes down to a combination of which schools have the greatest need, where there is opportunity for stormwater capture (and corresponding funding from the Water Department), strong community leaders, and park access.

Once selected, the trust works with schools on a community-led design process spearheaded by students. From there, it works with architects and the district to turn the kids’ dreams into reality.

The trust is not the only group with an interest in shelling out cash for playgrounds. The Eagles Foundation has paid for roughly a playground a year in Philadelphia for more than a decade; Wells Fargo funds them, too. The Lindy Foundation is interested in how to build playgrounds affordably, and the William Penn Foundation is concerned about integrating outdoor education into play spaces.

After a couple years of requesting and being denied any money for a playground from the school district, Lugo, the principal at Lowell Elementary, finally got lucky. The district connected Lowell with the Trust for Public Land to begin work on a playground in 2018. Architects guided Maurice Barnes’ third-grade class through brainstorming and drawing exercises. They covered basic accounting by teaching them to budget for equipment they could afford, and simple geometry by measuring the area of the schoolyard so they understood what could realistically fit there. The trust is also building a playground at Benjamin Franklin Elementary in the 19120 zip code.

By the time the Lowell project is complete, Maurice will have graduated from Lowell and will attend nearby Grover Washington Jr. Middle School. He’s still excited about having a playground across the street.

“I’m gonna come home from Grover, change my clothes after I’m done with my homework, and I’ll go straight to the park,” he said.

The school playground as a destination is exactly what Principal Lugo is going for.

“Hopefully,” he said, “when this area is created and available, what you’ll hear families saying [is], ‘Let’s go to Lowell. Let’s go to the Lowell playground.’ ”

—

PlanPhilly contributor Sophie Finn contributed reporting to this article.

This reporting was made possible in part with support from the Solutions Journalism Network and the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.