Time running out to save historic ‘MLK House’ in Camden

That structure is now on the verge of collapse in the face of indecision by local and state officials.

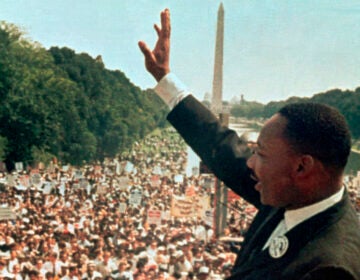

Martin Luther King Jr. stayed in the back bedroom of this house (left) on Walnut Street in Camden, according to the owner who inherited the property from her father-in-law. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Thelma Lowery remembers a day in June 1950 when two young men at her family’s home discussed staging a sit-in at a bar in Maple Shade, New Jersey.

“Daddy told them” not to go, Lowery recalled in a 2017 interview. “And Martin said, ‘Well, it’s a free country, you know. They shouldn’t be segregated, you know.’ And they went. And they got locked up.”

The “Martin” in her story is Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., then a 21-year-old seminary student studying at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, planning one of his first acts of civil disobedience. It culminated with the white tavern owner firing a gun in the air.

And the setting was 753 Walnut St., a two-story row house in Camden owned by relatives of King’s classmate.

That structure, which local activists want to preserve as a key waypoint in King’s early development, is now on the verge of collapse in the face of indecision by local and state officials.

Patrick Duff, a small-business owner from Haddon Heights who has led the preservation effort, said the house is unoccupied and degrading quickly, with water leaking from a gash in the roof and holes forming in the floors.

“The house is going to fall down,” Duff said. “If it doesn’t get saved in the next year or two, it’s done.”

All the while, the state Department of Environmental Protection continues to mull over a preliminary application, which Duff first filed in 2015, to have the house declared a historic landmark.

Designation by the state is required before the site can be placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Both state and national recognition would make the property eligible for badly needed grants and give it some protection from development or demolition.

Duff said he would launch one last push to break the bureaucratic logjam, starting with a legal motion this week to gain access to internal DEP emails about the property that were redacted or denied in a series of public records requests.

“They’re more redacted than the Mueller report, and we’re talking about a historical home that Martin Luther King once stayed in,” he said. “They’re obviously hiding something. So that’s what I’m going try to do, is find out what they’re hiding.”

A curious reversal

What started as a feel-good discovery five years ago about King’s connection to Camden has now degenerated into a heated debate over the home’s historical bona fides and acrimony over the state’s inaction.

Duff, who is also an amateur historian, said he discovered the significance of the Camden house while researching the Maple Shade incident. On a police complaint filed after the sit-in, King gave his address as 753 Walnut St.

Duff thought it was another aspect of New Jersey history that state residents would want to celebrate.

“To know where Washington crossed [the Delaware River], people should also know where Dr. King began, where his first sit-in was,” Duff said.

In the months after that discovery, there appeared to be consensus in officialdom on the need to preserve the structure. Camden Mayor Dana Redd and U.S. Rep. Donald Norcross, who represents the city in Congress, wrote letters urging the DEP to protect “a physical reminder of the profound role that Camden played in the shaping of our nation’s greatest civil rights leader.”

The New Jersey Legislature unanimously adopted a resolution calling for the same.

And most forceful of all, Georgia Congressman John Lewis, a King contemporary and civil rights icon in his own right, visited the site in 2016 to endorse its historical significance.

“This place of historic real estate must be saved for generations unborn,” he said.

But the state Historic Preservation Office, within the Department of Environmental Protection, then took the unusual step of commissioning a study on the home’s historical significance.

In late 2017, researchers at Stockton University released a report that downplayed the time King spent at the house. They acknowledged that King likely spent at least some time there with his classmate’s family, including the night of the Maple Shade incident, but threw cold water on the idea — asserted by some — that King ever lived at the house.

The skeptical study was followed the following year by news that Camden had diverted a $229,000 grant earmarked to save the house to its fire department.

Since then, the DEP has been reticent about why it has taken so long to decide whether to deem the site a historic landmark. “The DEP is preparing a response to the application,” an agency spokesman said when asked to comment last week. He did not provide a timeline.

Duff seethed with frustration when discussing the project last week. He said it doesn’t matter whether King lived in Camden or just spent time there with his classmate’s family.

“To know and to find out where his first sit-in took place, to know that the way that sit-in was formulated happened at 753 Walnut Street … if that’s not significant, then the sun is not significant to the grass,” he said.

Neither the Maple Shade bar nor the Crozer Theological Seminary are still standing, so the Camden house is the last remaining connection to that event.

Duff said it could cost anywhere from $200,000 to $500,000 to rehabilitate the house, and ideally he would like to turn it over to Mighty Writers, a Philadelphia-area nonprofit.

“They would teach children how to read and write out of the house where Dr. King formulated his first civil rights incident,” he said. “You can’t get much more inspirational than that.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.