These retiring teachers won’t get a final goodbye — so we’re telling their stories

As odd a time as it is to graduate school, it’s just as odd a time to retire from a career working in schools. Meet five people navigating those emotions.

Listen 6:32

Susan Ohrt, a music teacher at Myers Elementary School in Elkins Park, will retire at the end of the school year. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

When the coronavirus outbreak canceled traditional school graduations, the Class of 2020 received a well-deserved wave of sympathy.

There have been celebrity-studded tributes, television commercials, and too many Instagram posts to count.

But seniors aren’t the only ones leaving their schools for the final time under these often stressful and surreal circumstances.

In June, retiring teachers and school staff will leave their classrooms without any of the traditional rituals that mark the end of an academic year — or a career.

In tribute, Keystone Crossroads brings you the stories of Pennsylvanians who served their school communities for decades.

Susan Ohrt

Job: Music teacher

School: Myers Elementary — Elkins Park, PA

Susan Ohrt has been the music teacher at Myers Elementary School in suburban Montgomery County for 33 years. It’s the only teaching job she’s ever had — and the only for which she ever interviewed.

“It’s been my dream job,” she said.

That passion showed up in the classroom — where students, like Tremayne Diggs, could sense Ohrt’s zeal for teaching.

Diggs was a first-grader when Ohrt started — and she quickly became a lifeline for him as he dealt with the death of his own mother. Ohrt recruited Diggs to join a community choir she ran in a far-away suburb, and would ferry him back and forth to practices.

“She made sure I didn’t fall to the wayside,” said Diggs.

Music would become a cornerstone of Diggs’ life. He spent years in that choir (which also featured American Idol runner-up Justin Guarini), and then later attended Westminster Choir College, Ohrt’s alma mater. Not surprisingly, Ohrt helped Diggs apply to the school.

“She changes people,” Diggs said.

This would normally be a raucous, joyous, busy time of year for Ohrt. The spring is jammed with year-end concerts and performances.

On the final day of school, there’s usually a grade-promotion ceremony where the kids dance and sing songs — including the school anthem, which Ohrt wrote.

“It all just looks like joy,” she said.

Ohrt knew she was going to retire last spring, but decided to teach one more full school year so she could savor all the little milestones that dot the academic calendar.

She was particularly excited for the annual spring concert, which ends with a big singalong. Ohrt’s students join forces with adults from a community choir that Ohrt also directs — and she always puts the lyrics on the show program so parents can join in.

Those memories — of a crowded room singing in unison — are some of her favorites as a teacher. And this year she picked a song that seemed to capture the spirit of that moment perfectly: “Crowded Table” by a country supergroup called the Highwomen.

Now, given social distancing, the song’s title seems like a taunt. There aren’t many crowded tables these days. And, of course, the spring concert never took place.

“It’s just gut-wrenching at this point,” Ohrt said. “I haven’t been able to listen to [the song] since we’ve been home,” she said. “It’s too sad.”

Still, a verse echoes through her head.

“If it’s love that we give,” the song goes. “Then it’s love that we reap.”

Back in 1987 — when Ohrt began teaching — she had a four-page teaching philosophy that she’d penned as an undergrad. It was well thought-out, she remembers — cerebral.

Now, her entire teaching philosophy is bound up in the lyrics of “Crowded Table.” If you give love, you reap love. And that love is there, even if you don’t get a chance to belt it out standing side-by-side.

“Love is the foundation,” Ohrt asid. “When you’re a younger teacher, you don’t go there in a certain way. But as I’ve gotten older, love is my mantra.”

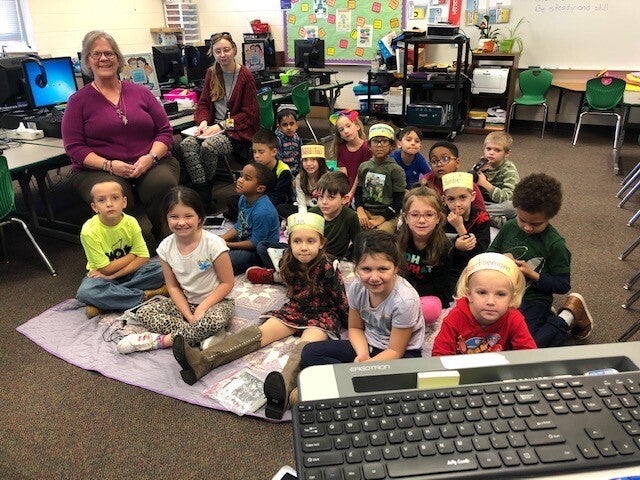

Carol Dittoe

Job: Digital literacy teacher

School: Octorara Primary Learning Center — Atglen, PA

By 1997, Carol Dittoe had already been a full-time educator for 20 years — mostly in the Lancaster area.

But when a part-time teaching job opened up in the Octorara Area School District, she jumped at the chance.

It wasn’t because she wanted to teach less. It was because after two decades she’d finally get a chance to teach her favorite subject: technology.

“It’s just so fascinating,” said Dittoe, 65. “I’m still a techno geek.”

Her mechanical inclinations trace back to childhood. Dittoe’s father was an appliance repairman in the Boyertown area, and he’d give her old radios to take apart and reassemble. Although her early teaching career took her away from tech, Dittoe always hoped to get back some day.

“It is so neat because it’s never the same,” Dittoe said.

She walked in on her first day in 1997 to find a lab full of IBM computers — models so old they required separate disks to turn on, start a program, or save work. The school had only one computer that connected to the internet.

Things have changed a lot since then — for her and the subject she teaches. Dittoe earned a doctorate in education in 2008, the same year she got on Twitter.

After years teaching middle school, she now works on digital literacy with students as young as kindergarten. She even teaches them the fundamentals of coding.

“Oh my god, they love it,” Dittoe said. “A lot of people say they’re too young — [that] they don’t know how to do it. [But] they don’t know that they don’t know.”

A cancer survivor who is now immunocompromised, Dittoe is somewhat relieved to be retiring. She doesn’t envy the teachers who may have to return to their classrooms next year and risk their health in the process.

But that hasn’t made this long, stilted goodbye any easier. She tears up thinking about her last group of middle schoolers, who are all high school seniors this year. She so wanted to attend their graduation ceremony.

“Having this abrupt ending happen, it’s just been… different,” Dittoe said. “I’ve struggled. I’ve been depressed. I’ve been sad, nervous.”

To say goodbye, she recorded a digital farewell video to her students — an act that would have been technologically and emotionally unthinkable when she started teaching in 1978.

“Make good decisions and always follow your dreams,” Dittoe said at the end of the clip. “Take care. And I will miss you.”

Que Travis

Job: Nurse

School: William Meredith School — Philadelphia, PA

As a nurse in elementary and middle schools, Querethea “Que” Travis always imagined herself as a sort of medical detective.

“You’ve got to be Dick Tracy,” she explained.

By that, Travis meant you need to sleuth for why a child has come to the nurse’s office.

It could be a fever, a stomach bug — some sort of medical ailment. Or it could be that what the student really needs is a mental respite from a terrible, horrible, no-good, very bad day. And perhaps the best cure is a glass of water, a few crackers, and 10 minutes of calm in Nurse Travis’ big, red chair.

“If they just need a little bit of time, I want to give that to them,” Travis said.

Travis, 62, has been working as a nurse in Philadelphia schools since 1996. It’s been a full-circle experience for her.

When she was a junior at West Philadelphia Catholic High School, she’d narrowed her career choices to nursing or teaching. Both fields interested her — and as an African American girl in the 1970s, those felt like the two main professions open to her.

“We were steered in certain directions,” Travis recalled, before quickly adding:

“I don’t regret it. I don’t regret it.”

In the end, she found a career that combined nursing and education. She was not merely an accessory to the academic process as a school nurse — she was often central to it.

Travis would detect hearing or sight issues that could hamstring a student from realizing his or her potential. She’d rap on doors in the neighborhoods where she worked to make sure families knew her and knew she was serious about getting their kids the best medical care. And if a child needed mental health services, she’d make sure she referred them to the right places.

“I always treat the children as I want my children to be treated,” Travis said. “I want them to know that someone cares about them.”

Her decision to retire comes as her husband recovers from leukemia. She wants to make sure they have time to spend together.

Being a school nurse in Philadelphia is a demanding job. Budget cuts sometimes forced her to split her weeks among three different schools.

Thanks to fundraising by the local parents group, she was able to spend her final years at William Meredith Elementary in the city’s Queen Village neighborhood. She always envisioned a big send-off party with her and the other retirees.

To not have that kind of goodbye has been “humbling,” Travis said.

But she’d rather not dwell on the bitterness.

“This is not a goodbye,” Travis tells the families and staff at Meredith. “It’s just a see ya later.”

Arline Billbrough

Job: Librarian

School: William Meredith School, Philadelphia, PA

Arline Billbrough rarely held the actual title of “librarian” at Meredith. She started as a parent volunteer before acquiring a pair of part-time titles — “Noontime Aide” and “Support Service Assistant” — that afforded her a small wage.

But through it all — over 20 years — she was, in her words, “the keeper of the books.”

She was the volunteer-turned-employee that kept a small school library thriving in a public school system where libraries are a rarity.

The story starts with Billbrough’s own love of reading — one she nurtured during her childhood in Camden, New Jersey. She was a smart kid, and perhaps a bit hyperactive. To keep herself occupied when she finished her work early, she’d bury her head in a book.

“That kind of saved me from being in trouble all the time,” Billbrough, 67, explained. “I would read constantly.”

In 1999, when her own child was in second grade, Meredith lost its school librarian to retirement. There was no money in the budget to hire a replacement.

“It was personal,” Billbrough said. “I just thought, ‘This is crazy. How can you not have a library in an elementary school? This is when you instill a love of reading in children.’”

Billbrough got a $500 grant from the school’s parent group to repaint the library a more vibrant color (she chose turquoise). She gave herself a crash course in the dewey decimal system. And then she went to work updating the collection.

Almost all of the books, Billbrough recalled, had white, male protagonists — just as they had when she was a kid. She focused on finding texts that featured female characters and characters of color.

“Part of that was trying to find out history and school myself with things I wasn’t taught as a child,” Billbrough said.

She relished her role as a book matchmaker. A child would wander in, looking for a book to read, and she’d pepper them with questions about their interests. Then she’d find that perfect book — the “hook” that would fuel their curiosity and love of reading.

“You know it’s there,” Billbrough said. “You have to find it — that spark in them.”

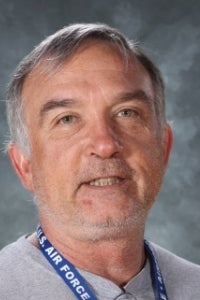

Mike Stewart

Job: IT Director

School: Blue Ridge School District — New Milford, PA

Though IT director is his official title, Mike Stewart, 62, prefers the label a student gave him years ago.

“I like to call myself the computer janitor,” he said with a chuckle.

‘Computer janitor’ always felt like a better description of the work he does and the clothes he wears.

“I dressed like one of the janitors — not like one of the teachers,” Stewart said. “[I] usually wear blue jeans, t-shirts whatever. I get dirty, run cable, whatever.”

Stewart’s worked dirty jobs since the fifth grade, when he got his first gig feeding and cleaning up after cattle in his hometown of Conklin, New York — right across the Pennsylvania border.

He started tinkering with personal computers in the early 1980s when he was in the Air Force. A handful of machines “magically arrived” in the office area where he worked. So he and a buddy started to tinker.

“I thought to myself, ‘Gee, if Jack can do it so can I,’” Stewart said. “So I sat down and I started writing programs.”

After he left the Air Force, Stewart wound up with a technology help-desk job that he hated. He hated it so much, in fact, that he was about to take a job as a prison guard when someone mentioned that a nearby school district needed an IT guy.

Stewart has spent the last 22 years in a pair of rural, Pennsylvania school districts, ushering them into the digital age. He feels lucky to have landed in a role where he gets to help people, and find ways around problems that can feel intractable.

But he’s looking forward to retirement. He knows the coming months — as schools figure out a transition from online learning to in-person school — will place a lot of demands on IT workers.

“And I really don’t feel like doing it,” Stewart said with a roaring laugh. “As sad as that sounds, I’ve been through enough changes in the last 22 years.”

“I will miss the people I work for,” he added. “This is a wonderful place to work… But I kind of like the idea of being able to sneak out the back door.”

Stewarts wants to travel around the country with his wife. He wants to savor life before his achy hands and knees catch up with him.

“I’ve been working for 50 years,” he said.

Cindy Layton

Job: Spanish teacher

School: Southern Fulton Junior/Senior High School, Warfordsburg, PA

Back in the summer of 1985, Cindy Layton was 21 years old — fresh out of Bloomsburg University — and deciding between two teaching jobs.

The principal at Southern Fulton Junior/Senior High School said that if she became the Spanish teacher, she’d also have to coach volleyball — a sport she’d barely played.

“I was kind of intrigued,” said Layton, now 56.

The volleyball thing stuck for about a decade, but the teaching job stuck a lot longer — 35 years.

For various stretches of her career, including now, Layton has been the only foreign language teacher in this tiny district near Pennsylvania’s border with the Maryland panhandle. Because of that, she sees herself not just as a Spanish teacher, but as a connector between the kids in her community and the world beyond.

“They’re from this rural town,” Layton said. “A lot of them didn’t get a chance to travel that much.”

Every other year she takes her students on a summer trip to a Spanish-speaking country, and it’s tremendously gratifying to later learn that those trips inspired some of her students to travel more.

Layton has always liked working with kids. She babysat a lot when she was growing up in Montoursville. Among her favorite clients was the Mussina family, and their little boy, Mike, who went on to become a Hall of Fame pitcher for the Orioles and Yankees.

The relationships between teacher and student can be especially strong when you’re the only language teacher in a district. Take the 18 seniors in her highest-level class this year. She’s taught all of them since they were in ninth grade.

A little over two years ago, a couple of the students in that core group wanted to decorate the room with a long, paper-link chain. Each chain would be numbered to represent the days left until their graduation. And the colors would correspond to the patterns of various Latin American flags.

Layton loved the idea. She later revealed to them that their last day would also be her last day. She was going to retire in two years to spend more time with her mom, who has Alzheimer’s disease.

The chain had about 50 links left when they ended up leaving school for the last time. When she returned to school in late May to clean out her room, the chain was still hanging on her wall.

“They knew and I knew that we were gonna go out together,” Layton said. “That was the plan.”

Show your support for local public media

Lisa Curcio

Job: ELA and Social Studies teacher

School: Chester A. Arthur School, Philadelphia, PA

On summer afternoons in the 1970s, you could find Lisa Curcio in the garage of her home in Philadelphia’s Roxborough neighborhood.

Doing what?

Teaching her version of summer school.

Curcio was just a student herself at the time, but she’d always felt called to teach. She asked her own teachers for spare books and papers so she could hold her own “classes” with neighborhood kids. When fall arrived — and her “students” went back to school — Curcio would carry on.

“During the school year I would teach a pretend class,” she said. “Like, nobody was there and I would just teach. I loved it.”

Curcio ended up spending the bulk of her 28 year career teaching middle school students in Philadelphia. The job challenged her, thrilled her, and took her to almost every corner of a vast and diverse city.

The last few months have been difficult. She feels she’s adapted as well as she could to online learning — and done her best to keep her eighth-graders engaged. But it’s hard to feel totally complete or satisfied with this ending.

“I wanted to close my door this year knowing that I did everything I could do for all the time that I was there,” said Curcio. “And I can’t do that, only because of the circumstances.”

It’s not all gloomy. Retirement still beckons. Curcio, who will turn 60 two days before school ends, has visions of the fall in her head.

“I have always imagined the day I could go to the beach in September,” she said with a chuckle. “And make sure that I send all my friends a picture.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)