The savings gap

Should schools put poor children to work so they can learn how to work?

That’s what Newt Gingrich told a Harvard audience last month, when he argued that public schools should pay kids to perform janitorial duties. “Really poor children in really poor neighborhoods have no habits of working and have nobody around them who works,” Gingrich later explained, in defending the remark.

As critics were quick to point out, Gingrich was repeating one of the most bigoted myths in our politics. In reality, three-quarters of poor Americans work, and most poor children live in a household with at least one parent who is employed. So such children see plenty of people who put in an honest day’s labor.

But poor children – and, for that matter, those from middle-income families – see far fewer examples of people who put aside much of the wages they earn. Across social classes, in fact, Americans save much less than their counterparts in countries such as Germany, France, and Sweden. Rather than teaching our kids how to make money, then, schools should be teaching them how to stash it away.

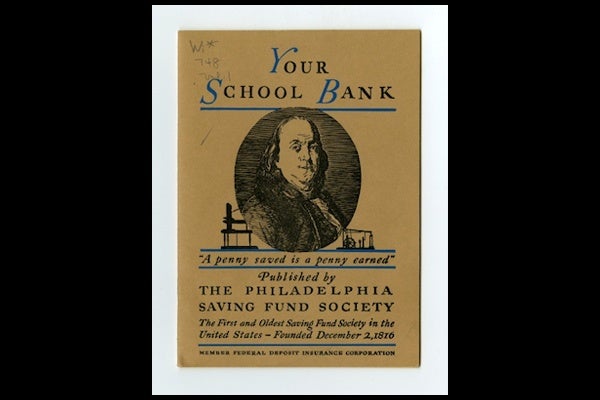

It’s happened before. Starting in the 1870s, American public schools established their own student savings banks to promote habits of frugality and thrift. By 1929, on the eve of the Great Depression, more than four million youngsters had accounts in school savings banks.

Here’s how it worked: Every Monday morning, the teacher would call roll and ask each student who wanted to make a deposit to come forward. When a student’s account reached 50 cents or a dollar, the student received a savings book issued by a cooperating local bank. And when an account reached $3, the student began earning 3 percent interest on it.

Some schools engaged students as “tellers” who could collect and record deposits. And most strongly discouraged students from taking money out of their accounts. Parents often had to approve any withdrawals of more than 25 cents, while some schools barred any withdrawals before “Bank Clearing Day,” near Christmas.

Sara Oberholtzer, a Philadelphian who was the nation’s best-known advocate of school savings banks, said students of every social class stood to benefit from them. The banks would “stimulate the poor to provident habits,” Oberholtzer wrote in 1892, “and prove to the middle classes the foolishness of spending all as they get it.”

That became especially important in the early 20th century, when businesses began to target youths directly with advertising campaigns for chewing gum and other products. Without school savings banks, another advocate wrote, children would fall victim to “the candy habit.” They would also waste their money on movies, which lured them with garish marquees and billboards.

Schools reinforced the saving message in their daily lessons, especially during “National Thrift Week.” Held in January, shortly after the holiday spending binge, the week featured essay contests on such themes as “What I Am Saving For.” Schools also staged pageants like “How Money Grows,” in which students playing pennies, nickels, and dimes berated a profligate girl named Spendthrift for wasting them on candy and movies. “Money,” Spendthrift concludes, “will not grow unless it is planted in a saving fund.”

But school savings banks declined during the Depression, when many of the cooperating banks went bust and took the children’s money with them. And as America emerged from its economic doldrums in the 1940s and ’50s, children were increasingly urged to spend rather than save.

On television, a powerful new medium for reaching young consumers, kid-friendly shows encouraged children to purchase the sponsors’ products. If you watched Howdy Doody, you found out that Howdy Doody himself liked Wonder bread. And kids learned about Mattel toys from The Mickey Mouse Club, which transformed the company from a small start-up into a global giant.

In schools, meanwhile, the message was the same: Buy, buy, buy. School stadiums, vestibules, and even textbooks bore advertisements for soda, clothing, and other products. And courses such as “consumer math” replaced lessons on thrift, teaching students the best ways to spend their money instead of the virtues of setting it aside.

By the 1990s, Mattel had joined MasterCard to introduce Cool Shoppin’ Barbie, who came with her own mock credit card (a MasterCard, of course) and a scanner programmed to say, “Credit approved.”

Is it any wonder that Americans are drowning in debt? In 2004, 12 percent of families with annual incomes between $50,000 and $99,000 were in “debt hardship” – that is, they were devoting more than 40 percent of their income to servicing credit card debt. Even among families making more than $100,000, 7 percent were suffering debt hardship.

We need to teach our children to be more frugal than we are. And to do that, we should take a page from our parents and grandparents – and from their schools. School savings banks are enjoying a small revival in several states, where kids are again discovering the virtues of deposits over withdrawals. More than ever before, it’s a lesson we all need to learn.

This article was orginally published in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.