Meet the fighting dinosaurs of Trenton

They’re back!

The skeleton of the Dryptosaurus, the world’s first carnivorous dinosaur, has been reassembled in the New Jersey State Museum’s natural history hall.

Written in the Rocks: Fossil Tales of New Jersey takes visitors back in time to explore the geology of New Jersey. The oldest fossils from the state provide clues about our ever-changing planet and how fish, amphibians, turtles, birds, reptiles and mammals have evolved and adapted.

“We are very excited to have life-size dinosaurs in the Natural History Hall again,” says Curator of Natural History David Parris. “Dinosaurs were a highlight for generations of New Jerseyans who visited the museum, and we are pleased to once again be able tell the story New Jersey’s role in the discovery of these fossils.” The Dryptosaurus, a cousin of Tyrannosaurus Rex, was discovered in southern New Jersey in 1866.

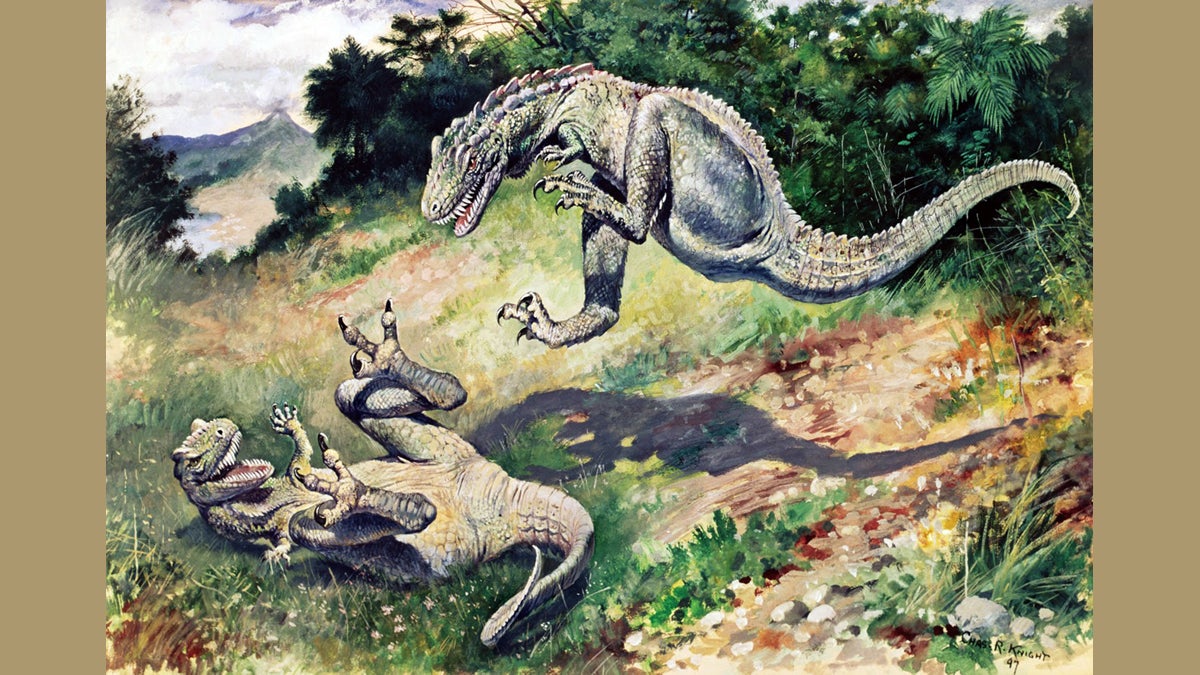

The museum commissioned the Dryptosaurus model from Research Casting International, using the museum’s casts of the original specimen and paleoartist Charles R. Knight’s 1897 painting of Dryptosaurus fighting.

Charles Knight’s dinosaur watercolors were a popular attraction at New York’s American Museum of Natural History.

Although not around when the dinosaurs were, Parris has been at the museum for a long time. As he passes a fire extinguisher, whose door has come ajar, and pushes it shut, he says “I’ve been closing that door since 1971.”

With master’s degrees in geology from Princeton University and paleontology from the South Dakota Institute of Mining and Technology, Parris worked his way up to becoming curator in 1985. “Geologically, things haven’t changed that much,” says Parris.

But the collection has vastly expanded, thanks to fieldwork done in recent years, from which 100 scientific publications were produced, showcasing the museum as an academic institution. “Not only have we added to the collection but to the knowledge of paleontology and geology of New Jersey and beyond,” says Parris. The museum does field research at its Natural History Field School in the Bighorn Basin of Montana, where the scientific environment during the Cretaceous Period (more than 66 million years ago, following the Jurassic Period) was similar to New Jersey’s. Today, the dense population and the built environment make it difficult to access fossils, “although most of our work is in New Jersey,” says Parris. “It’s a great place to live if you’re a paleontologist.

On a recent weekday morning, a group of 4- to 8-year-olds from Trenton’s Divine Kidz Academy filled a classroom, transfixed as Assistant Curator of Science Education Dr. Diane Bushman talked about chemistry, atoms and digging for dinosaurs. “These are a great group of curious kids,” she said. “They get to practice paleontology skills with tubs of fossils, figuring out which are real and which are models. It’s a chance to get messy, digging with trowels.”

“We love to get youngsters excited about these objects—we’re specimen people,” said Parris who, as a child, developed an interest in the biological sciences while living with missionary parents in Nigeria. “It was a wonderful mind-expanding experience to live in a foreign country. Children are interested in exotic things, and we show how they relate to New Jersey.”

Not only is the natural history hall humming with youngsters studying with Dr. Bushman, but volunteers and interns working in the laboratories add to the academic atmosphere.

Jason Fresolone, a North Hunterdon High School grad headed to Stockton College to study biology, has volunteered two summers at the museum, where he works with the shell collection. He recounts being an angry child until his parents took him to the American Museum of Natural History where he saw dinosaurs fighting and realized there was something in the world he really cared about.

Working with tubs of fossils and bones in the public laboratory, Laurel Nestor-Pasicznyk, a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts pursuing a career in scientific illustration, has been volunteering for three summers, and is co-authoring, with Parris, a paper on sea turtles, forthcoming in The Mosasaur, the journal of the Delaware Valley Paleontological Society.

What, exactly, are fossils? Are they the actual bones, or the impressions left in rock? “Fossils started as bone,” Parris explains, “and became the mineral that led to it being preserved.” Minerals, or stones, are examined by geologists, paleontologists, archaeologists and others to learn about the people and creatures who came before us.

In 2012, amateur fossil hunter Greg Harpel brought a bone fragment he found to Parris, who recognized it as a perfect fit with a fossil discovered in 1849. “Never before have two pieces of the same bone been discovered in different centuries and fit perfectly like puzzle pieces,” Parris said. The pieces make up the only known fossil from Atlantochelys Mortoni, an extinct sea turtle from Upper Cretaceous New Jersey.

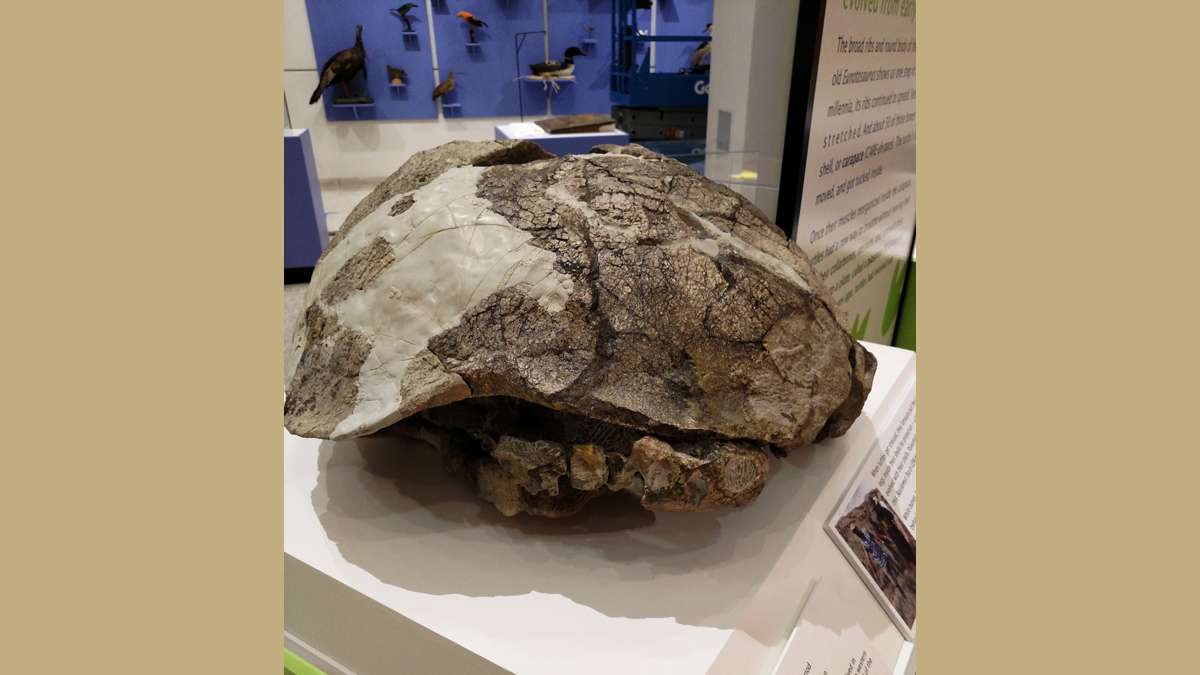

In another instance of piecing together the puzzle, the Basilemys turtle fossil from 60 million years ago was found shattered in Carbon County, Montana, during the Bighorn Basin Dinosaur Project’s 2013 field expedition. Parris and his team carried out the eroded fragments from the site wrapped in a blanket, then researchers used tiny air-powered jackhammers to slowly chip away the hardened iron carbonate mineral stone, revealing a nearly complete turtle. The fossil dates from the time that dinosaurs went extinct; “Basil,” as the fossil has been nicknamed, lived right alongside the last of the T. Rex and Triceratops and may be one of the most complete examples of this species.

New Jersey State MuseumNatural History Hall205 West State Street, Trenton

Museum hoursTuesday – Sunday9:00 am to 4:45 pmClosed Mondays & State Holidays

General AdmissionAdults: $5.00Children 12 and under: FreeSeniors & Students with valid ID: $4.00

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.