Philadelphia’s Tempesta di Mare honors the musical genius of 18th-century orphans

“Hidden Virtuosas” premieres Baroque music by the most downtrodden women of Venice, not heard in three centuries.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

A long time ago, in a place far, far away, orphaned girls found on the streets of 18th-century Venice were given music lessons. They formed an ensemble that became one of the international sensations of the Baroque era.

Through music education, these once-abandoned children grew up to be the toast of European society.

The story of the girls of the Ospedali, a series of charitable institutions in Renaissance Venice, had been little more than a footnote in music history, specifically a footnote in the biography of Antonio Vivaldi (“Four Seasons”), who for several years gave music lessons there.

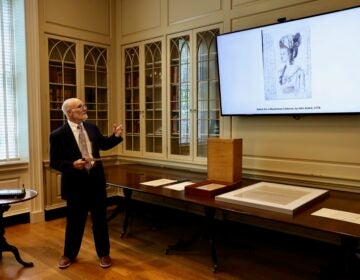

This weekend, the Philadelphia early music ensemble Tempesta di Mare will put the memory of the orphans front and center. “Hidden Virtuosas” is a program to perform modern premieres of music composed for, and in some cases composed by, the women of the Ospedali.

“I’m a professional wind player specializing in Baroque music. I’ve been that my whole adult life, but it has always been men’s music,” said woodwind player Gwyn Roberts, co-artistic director of Tempeste di Mare. “Not only written by men, with a couple of very small exceptions, but everybody who played it and directed it was male.”

“Except in this one, very specific place where the women were the stars,” she said. “They were the soloists. They played all the instruments, including wind instruments despite that being considered obscene for a woman to do. They directed the music. They ran their own rehearsals.”

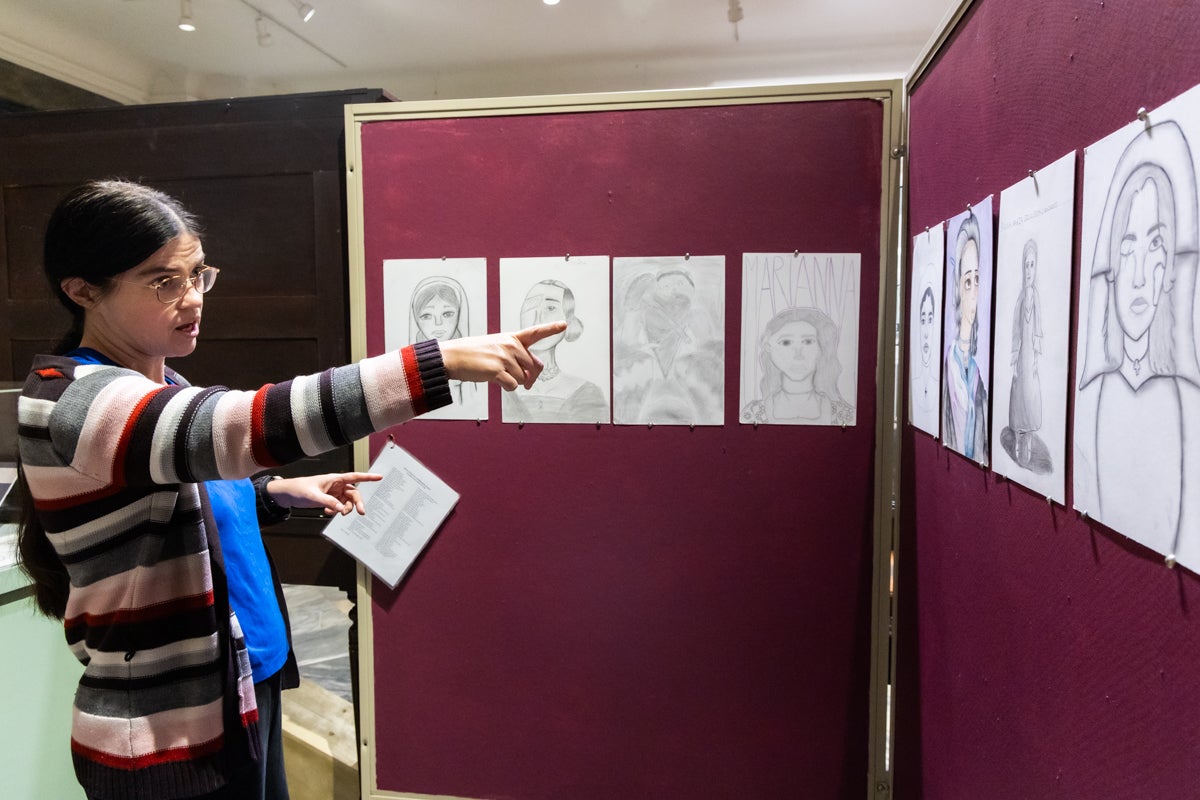

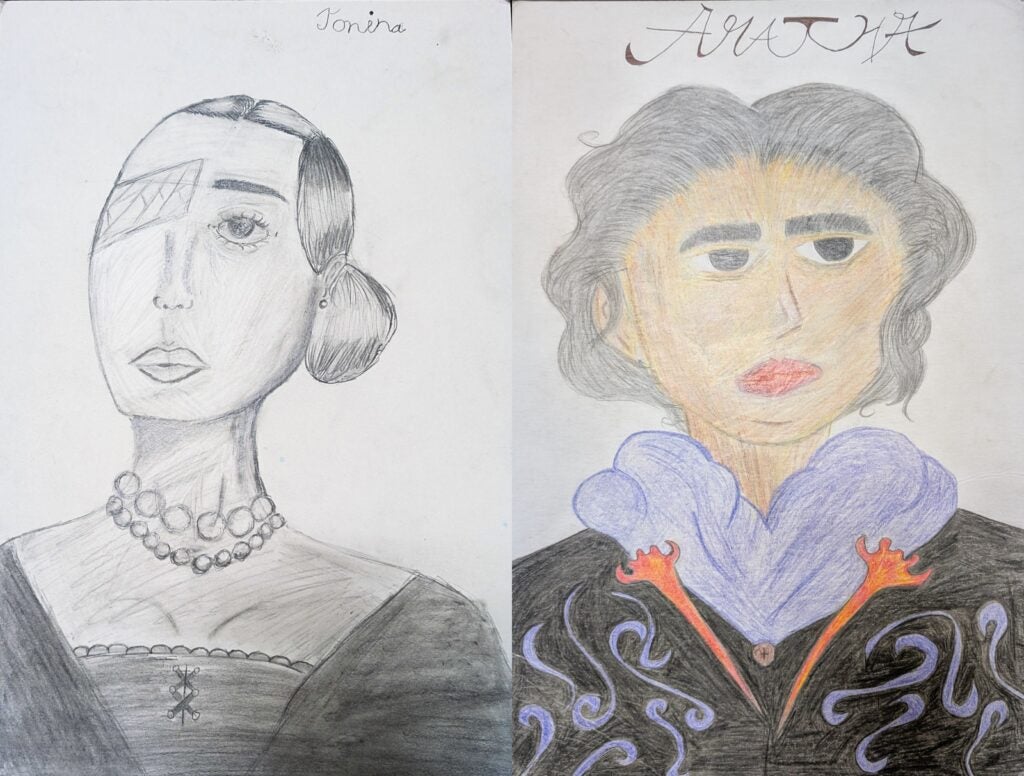

For the “Hidden Virtuosas” concert, the choral parts will be sung by students from Philadelphia’s Girard College, which also accepts orphaned or single-parent children for a K–12 education at no cost.

Roberts’ father was a student at Girard, and she sees the school as a modern-day equivalent of the Ospedali.

“Once I knew about the missions of the two places and the belief in the power of education and music to make life better, I wanted to involve Girard,” she said. “I wanted the students to have the experience of seeing themselves in history in this way.”

The Ospedali of Venice

The Ospedali of Venice was a set of four religious-based institutions set up in the 16th century to help needy people in the region. They included a home for “incurables” who were ill with disease; a place for people experiencing homelessness; an institution for the severely impoverished; and one for orphaned infants, or foundlings.

The Ospedali that took in children, mostly at the Pietà for orphans and the Mendicanti for beggars, taught them skills to set them up for more successful adulthoods. Boys were typically taught vocational skills and girls were taught domestic skills that would set them up to be homemakers.

Music education was considered essential, even for Venice’s most downtrodden charges.

“Music was part of Venetian culture and life,” said Vanessa Tonelli, a music historian from the University of Southern Mississippi who worked with Tempeste di Mare on “Hidden Virtuosas.”

“It was used for every religious celebration you could possibly imagine,” she said. “It was also used for a lot of civic celebrations, such as festivals and marches that would happen through the streets all year long.”

Obscuring genius behind a screen

Something unique happened at the Venetian Ospedali over the course of 200 years: The girls got good. Very good. The musical virtuosity of the orphans became so renowned that their chapel became a mecca for visitors from across Europe.

“A lot of orphanages might teach their children to sing to earn alms in the street, for example,” Tonelli said. “But in Venice, they taught the women to such high levels of performance that it went beyond anything that was happening at other institutions.”

People reportedly came in droves to hear the women of the Ospedali, but they were not allowed to see them. The religious institution believed it was improper for women to be seen performing instruments, particularly less modest instruments like woodwinds and the cello.

To avoid perception of scandal, the Ospedali ensemble performed on the balcony of their chapel, closed by a metal grate which obscured the audience’s view, allowing only the players’ silhouettes to be seen.

The obfuscation only triggered desire. Many men in the audience imagined the beauty of women capable of making such beautiful music. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, smitten by the sound of the women, pined to look behind the grate.

“What vexed me was the iron grate, which suffered nothing to escape but sounds, and concealed from me the angels of which they were worthy,” he wrote in his 1741 book “Confessions.”

Rousseau urged an administrator to let him look into the balcony, where his expectations were deflated. Being from poor and orphaned origins, many of the Ospedali players had birth defects and scars from smallpox and were underdeveloped from malnutrition.

Rousseau eventually conceded that the women of the Ospedali made beautiful music in spite of appearances.

“I left nearly in love with all these ugly faces,” he wrote.

In an historic homage to the grates behind which the women performed, Tempesta di Mare will perform behind a semitransparent scrim, which is opaque when lit from the front but nearly disappears when lit from behind. The concert at the Philadelphia Episcopal Cathedral will begin with the ensemble unseen, gradually becoming visible as the lighting changes.

Music as a path to a better life

Part of the reason for the musical excellence at the Venice Ospedali was likely the generational expertise that was handed down for many decades. Many of the girls who came in as orphans never left, becoming instructors and administrators at the institution, creating a hothouse of musical life.

Tonelli said that musical instruction allowed the orphans to raise their social status in Venice, lifting them out of poverty and dramatically changing their lives.

“The women musicians received more money for dowries than the non-musicians,” she said. “Some of them married notable merchants in the Venetian economy because they were desirable as spouses for their musical ability. Playing music was a step towards a more affluent life, especially if you’re abandoned with no parents and you have nothing as an orphan. Some of these women would receive hundreds of marriage proposals and were able to choose an entirely different life.”

The Ospedali’s modern-day equivalent

“Hidden Virtuosas” partnered with Girard College as its story parallels the Ospedali.

Girard was founded in 1848 by Stephen Girard, once the wealthiest man in the United States, for white, male orphans, legally defined at the time as children without fathers. In the 20th century, the school expanded admission to any child of any background from a single-parent household or functionally orphaned.

School archivist Kathy Haas said the arts have always been part of Girard’s curriculum, starting with drawing classes when the school opened in 1848.

“Vocal arts begins shortly after. By 1870, they formed a band,” Haas said. “Over 175-plus years, we’ve had just about everything you can think of, from swing bands to jazz bands to regular marching bands to orchestras, you name it.”

Like the Ospedali of the 18th century, Girard produced notable musicians of the 20th century, including C. Stanley Mackey, a tuba player with the Philadelphia Orchestra and leader of the Philadelphia Municipal Band. When he died in 1915, he was remembered as “one of the best-known musicians in the East.”

Girard is also the alma mater for rapper Tracey Lee, who had a hit in 1997 with “The Theme (It’s Party Time)” and later became an entertainment lawyer, as well as composer Joseph Hallman, who was nominated for a Grammy award in 2014.

Tonelli wants to re-write music history from the ground up, not the top down. Unlike the universally recognized composers of Baroque music who played in the courts of kings, the women of the Ospedali learned music from one another and played for themselves and their neighbors.

“A lot of the music that was written around the Ospedali and in Venice were by locals,” she said. “They were important figures in the community because they lived there and stayed there for many decades and contributed to what people wanted to hear, every day, every week.”

“Hidden Virtuosas” will be performed Friday and Saturday nights, Nov. 7 and 8, at the Philadelphia Episcopal Cathedral.

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series that explores the impact of creativity on student learning and success. WHYY and this series are supported by the Marrazzo Family Foundation, a foundation focused on fostering creativity in Philadelphia youth, which is led by Ellie and Jeffrey Marrazzo. WHYY News produces independent, fact-based news content for audiences in Greater Philadelphia, Delaware and South Jersey.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.