Surge in street ‘assassinations’ make 2021 Wilmington’s deadliest year for gun violence

Gun violence has been out of control in Delaware’s largest city since 2018. The mayor cites the “dissolution of social order” in some neighborhoods.

Listen 3:41

Photos, candles and bottles dominate the shrine for 18-year-old Zion Davis-Shelton, who was gunned down Oct. 24 in the unit block of West 27th Street. (Cris Barrish/WHYY)

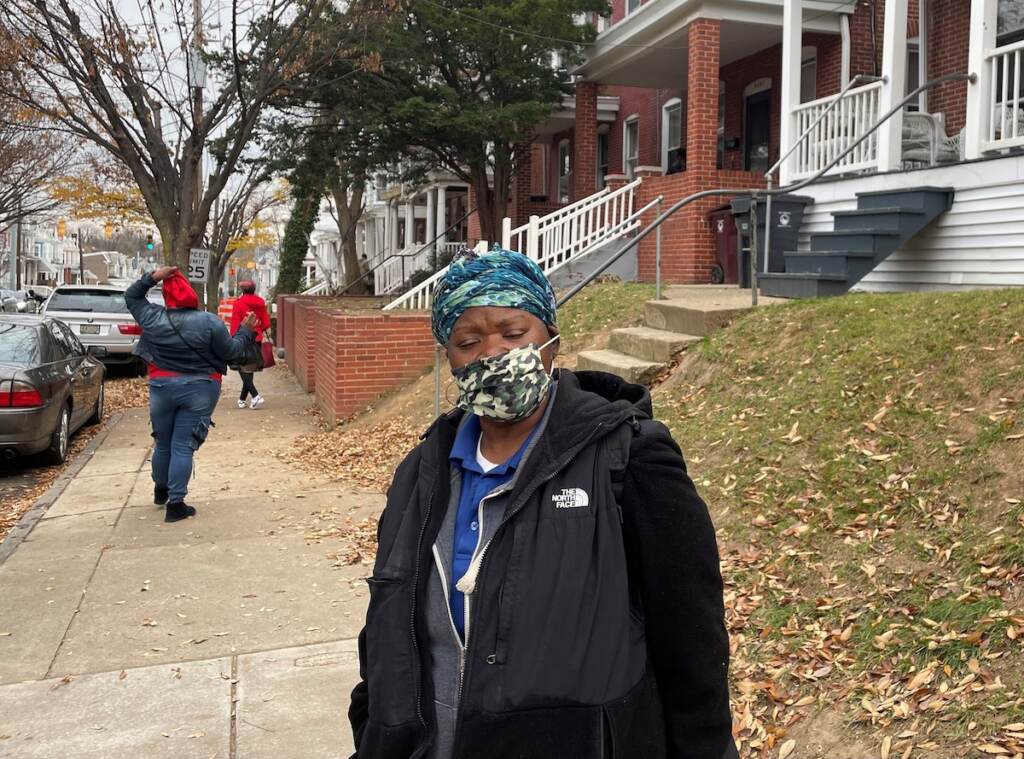

The carnage around Sharon Taylor’s home in Northeast Wilmington has become more than she can bear.

Three men have been shot to death within a few blocks of her home since late October, with the spot where they were killed marked by shrines. Several more people have been wounded there by gunfire in recent months.

“It’s really terrible,” Taylor said while she walked in her besieged neighborhood. “All I can do about it is just pray about it. People out here are going crazy, and they need to get their life together.”

Taylor’s perception that gun violence has been out of control in Delaware’s largest city is supported by statistics showing that with two weeks still remaining, 2021 has been Wilmington’s deadliest year.

To date, 39 people have been slain on city streets, all in a handful of low-income neighborhoods that essentially encircle the central business district.

The city of 71,000 residents has a gun fatality rate this year of 1 for every 1,820 residents. That’s two-thirds higher than Philadelphia’s rate, which also has seen record homicides this year.

To date 529 people have been killed in Philly this year, but Pennsylvania’s largest city has 1.6 million people. That’s a rate of one homicide for roughly every 3,000 people.

Wilmington Mayor Mike Purzycki said he doesn’t like to compare his city to others, especially Philadelphia, whose population is more than 20 times larger. But he agrees that the plague of shootings is devastating Wilmington’s Northeast, East Side, West Center City, Hilltop, and Southbridge sections. He cites the “dissolution of social bonds” in those neighborhoods as a driving factor.

While overall shootings are down in 2020, the fact the fatalities are way up — and that some have been captured on surveillance video in neighborhoods — unsettles the mayor.

“These have been assassinations. These have been assassinations,’’ Purzycki said, repeating himself for emphasis. ”We’ve had people just walk right up within two feet and just empty the firearm right in the back of someone’s head.”

“We used to have shootings where they seemed to be sending messages. Guys would be shot in the leg. Today you see these are very deliberate acts of homicide and that’s deeply troubling.”

One man visiting friends in a Northeast neighborhood said he recently had a relative killed. He said too many teens and young men are armed because they want to be feared on the street. Too often they are settling disputes over drug territory or insults by pulling the trigger, he said. The man would not give his name out of concern that he would be a victim of retaliation, another hallmark of the city’s continuing spree of gun violence.

“We say we’re in poverty, this and that, but we around here are killing each other. So it’s just too much play going on in the streets. That’s causing a lot of these kids wanting to have a rep,’’ he said while walking around the block.

“And it’s sad to say the rep nowadays, instead of being the football star or the boxing star or the basketball star, they want to be the star that bust a gun and kill someone.”

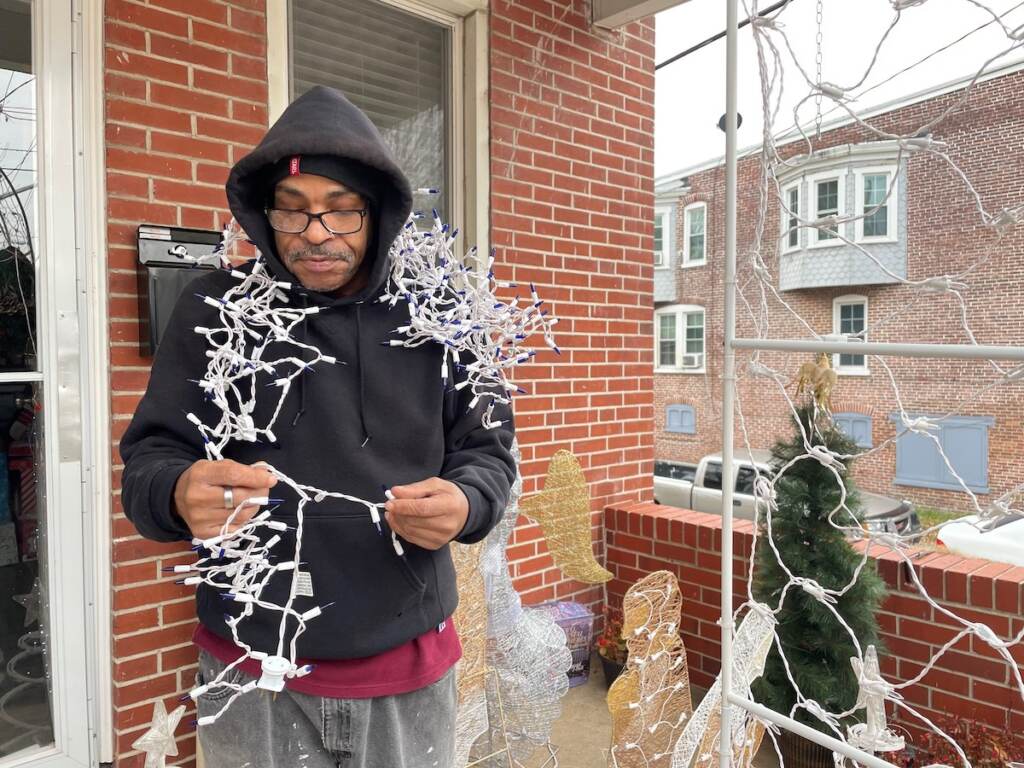

Nearby, on North Washington Street, Keith White was putting up Christmas decorations outside the row home where he lives with his mother. He says he hears gunshots ”all the time” in his neighborhood.

“It’s a shame,’’ he said. “You got no choice but to get used to it, as long as you keep hearing it. We’re all just trying to survive, but it’s hard, though.”

‘Everybody is affected. People are getting killed for what?’

So what can be done? Can anything stop the escalation?

Chief Robert Tracy’s data-driven strategy to direct police presence to so-called hot spots of violence paid big dividends in 2018, when just 81 people were shot and 17 of them died. He’s optimistic that approach can pay off again.

Since that promising year, the figures have been bleaker, even before the coronavirus pandemic began.

In 2019, 119 people were shot and 27 of them died.

In 2020, 169 people were shot and 30 died.

In 2021, 150 people have been shot so far and 39 killed.

Tracy said the pandemic and restrictions on gatherings first eliminated and then limited community meetings that police attended. That prevented police from fully implementing an intervention program where they meet with people deemed at high risk of violent behavior because of prior crimes or gang associations.

“Community engagement is one of the biggest things that you have to have, beyond any strategy. That’s been disrupted for the last 18 months,’’ he said, adding that despite the record fatalities, overall shootings are down since last year.

He said police will continue tweaking their strategy, but it will always be anchored in community outreach.

“As we’re coming out of this, we’ve got to make sure that we get back to some of the things that we weren’t doing because we were prevented from doing it. We’re finally getting back to in-person meetings with these communities that are suffering so we can have those face-to-face conversations.”

Tracy and Purzycki both want judges and prosecutors to be tougher on people arrested on firearm charges, saying that too many are back in neighborhoods too soon because they get freed while awaiting supervised release or post bond. Tracy said some of them have recently become victims of gun violence after getting out of custody.

“In a time where we have all this type of strife, you’re putting more people back on the street that are willing to carry firearms. It’s a gateway crime to a shooting or a homicide,” Tracy said.

Taylor, who cares for her grandchildren at her home, agrees that tougher penalties for those with illegal guns are appropriate. Mostly she just hopes and prays for anything that can make her neighborhood more peaceful.

“Everybody is affected,” she said. “They’re just tired of this stuff. You know what I mean? Don’t make no sense. People are getting killed for what?”

Purzycki said he empathizes with people in the neighborhoods where blood too often spills, and even understands those who are reluctant to provide information to the cops after they witness or have information about a violent crime.

“There’s generally a lack of cooperation on the part of people in the public because in many cases, they’re frightened. They don’t want to get involved in these things. So it’s just exhausting because we’re trying so hard and know our police officers are trying very hard. I have confidence in my police department.”

The current spike, Purzycki said, has crystallized to him how important it is to rebuild neighborhoods, especially those where the vast majority of residents are renters and too many properties are vacant and boarded.

“If you’re in a very fragile neighborhood, I don’t think sending in nonprofits to help out really works that much because I think that the community’s got to have a much bigger psychological stake in their own neighborhoods,’’ said Purzycki, a Democrat in his second four-year term.

“So if you have a lot of home ownership, people tend to be protective of their only asset, their home. They feel much more attached to the community rather than being transient.”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.