Study: Center City lost 7 percent of its public parking spaces in the last five years

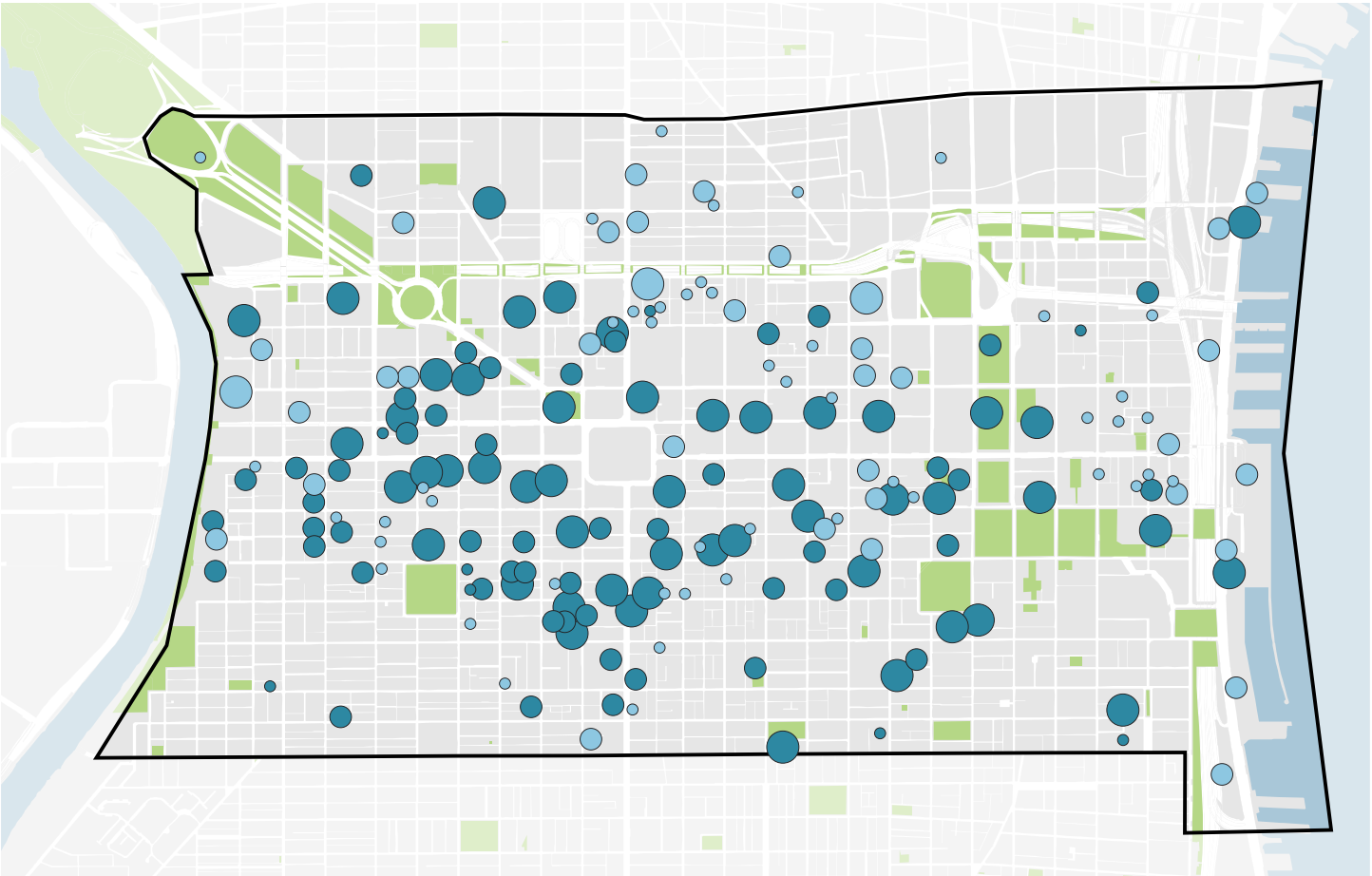

The Center City development boom reduced the number of public parking spaces by 7.2 percent between 2010 and 2015, according to the Planning Commission’s 2015 update to the Center City Parking Inventory.

The inventory, which the Commission updates every five years, found that about 3,623 off-street public parking spaces disappeared during this period as several lots and garages were replaced by high-rise buildings. A “public” space in this sense is one than anyone can rent, as opposed to a private space that’s exclusive to building tenants or employees.

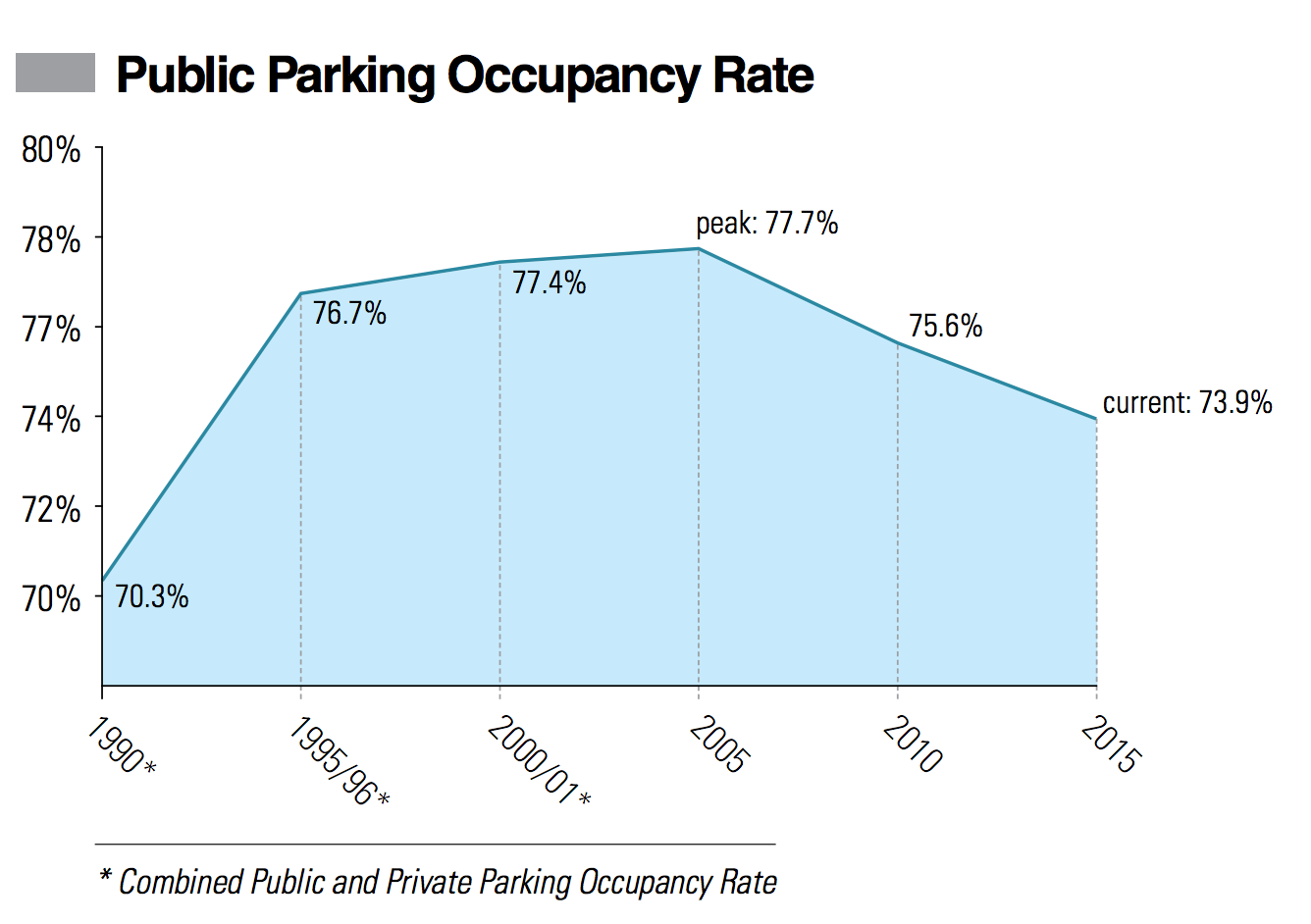

One might guess that losing more than 3,600 parking spaces in a five year span would drive up occupancy rates in the remaining lots and garages, but on the whole this hasn’t been the case. Counterintuitively, parking occupancy actually declined by 1.7 percent during this period, from 75.6 percent down to 73.9 percent. Parking occupancy peaked at 77.7 percent in 2005, so this is part of a 10-year decline:

In spite of the overall decrease in supply of parking spaces since 2010, occupancy rates did not increase; in fact, this is a slight decrease from 2010, when the occupancy rate for public facilities was 75.6%. This reflects a drop in demand for public parking spaces that is commensurate with the decrease in supply. While private parking facilities may have absorbed some of the demand, new Center City developments have also been associated with increases in employment and other daytime trip generators. Therefore, the stable occupancy rates in the face of a decreased supply suggest the presence of a modest shift away from the use of private vehicles.

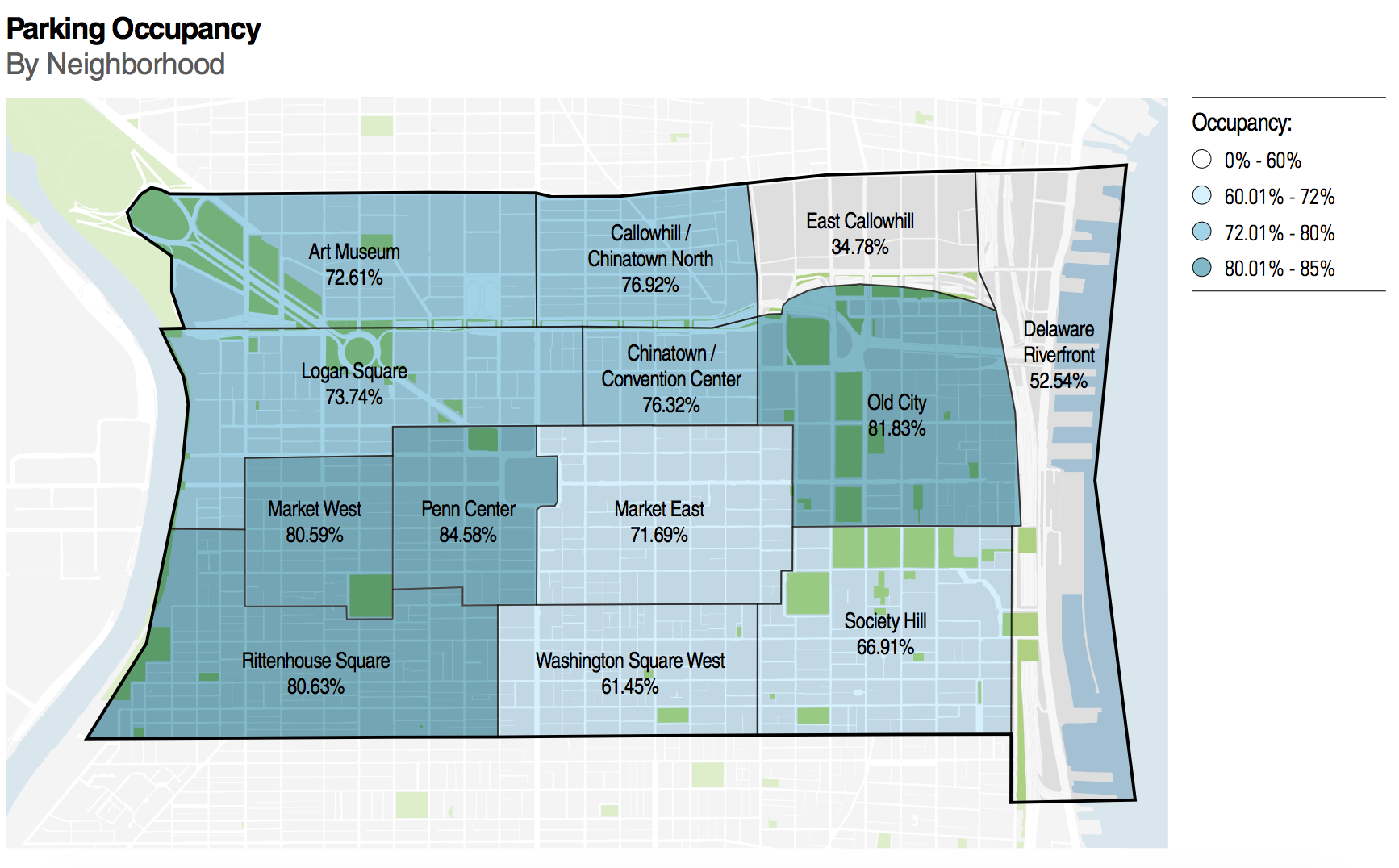

They also break down the occupancy rates for different neighborhoods within Center City:

Part of what’s happening is that some of the rentable public spaces in lots and garages have been replaced by dedicated parking spaces for residents, which throws into question just how many fewer cars are around these days.

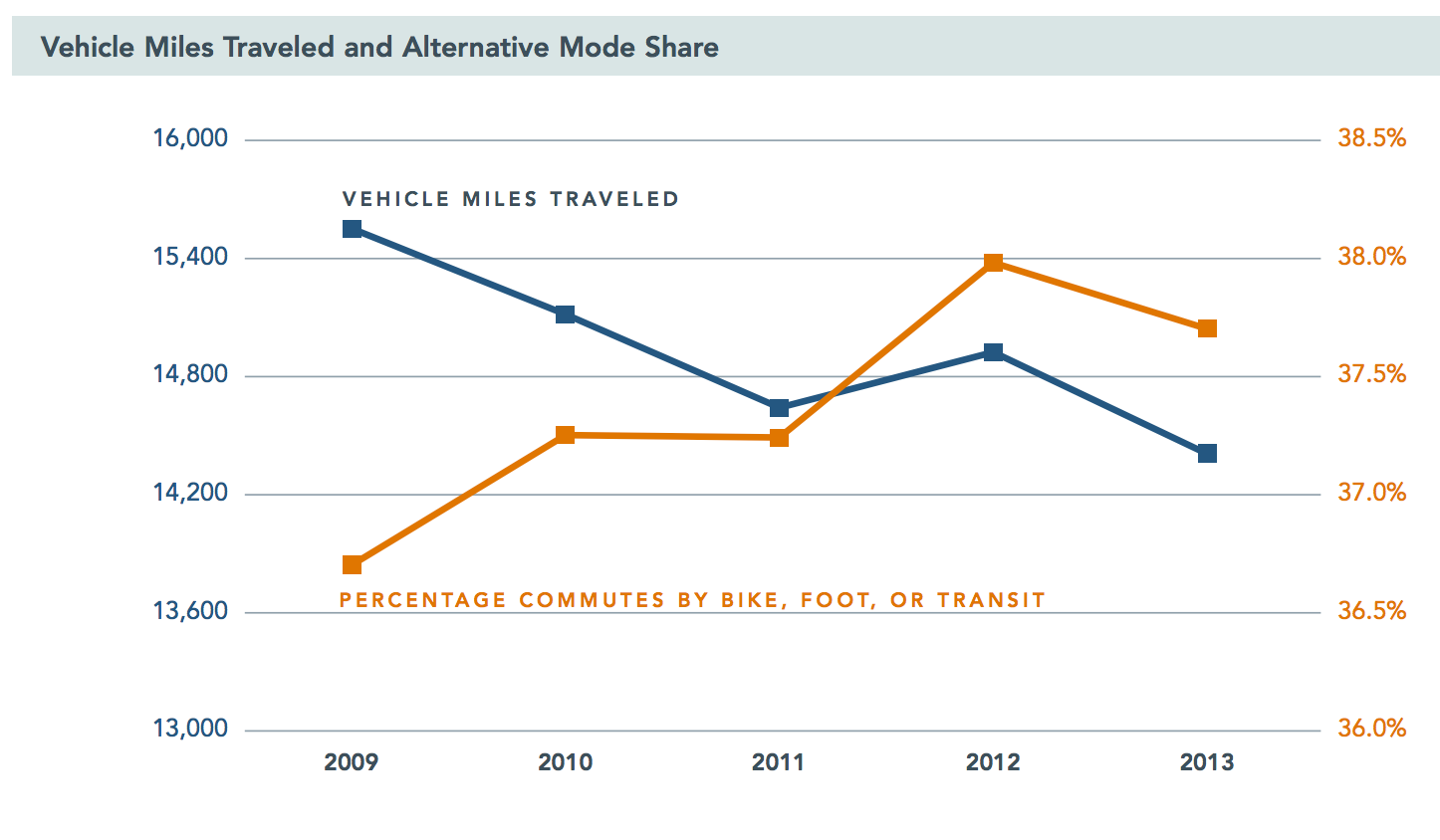

But the other part is that people really are driving less in recent years, at both the city and the metro level. The final Greenworks report from the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability showed that the Nutter administration achieved their target reductions in vehicle miles, and at the city level, car trips are down, while biking, walking, and transit trips are up.

And various analyses of Census data by Center City District and others have confirmed the intuitive notion that these trends are most pronounced in the denser, more urban parts of the city.

The idea that building more parking capacity will only increase the number of cars in a neighborhood, or conversely, that removing parking spaces can reduce the number of cars often gets short shrift at neighborhood zoning meetings, but the evidence here suggests this is basically how things work.

When parking lots go away, parking conditions tighten, driving becomes more unpleasant, and some people respond to this by ditching their cars. Rather than enduring permanent traffic jam conditions, neighborhoods simply level down to a new equilibrium with fewer parking spaces, fewer cars, and higher “alternative” mode share as parking gets tighter.

So if there is less parking demand in the Center City neighborhoods, why isn’t there any relief at the curb?

The issue is that curb parking is underpriced, the Planning Commission says, creating perverse consequences for individual transportation choices as well as the business incentives facing private parking operators.

Because City Council and the PPA set the prices for curb meters and residential permits so much lower than the rates for off-street parking, drivers have a strong incentive to seek out free or cheap curb parking first, before ultimately relenting and parking in a garage when things get desperate. The George Costanza parking strategy is a great example of a “smart for one, dumb for all” practice that makes sense in terms of individual incentives, but in the aggregate just adds up to a lot of unnecessary traffic congestion.

The Nutter administration has long been aware of this issue, and as early as 2009 they were saying publicly it was their goal to set curb prices at a level that would nudge drivers into a garage after an hour or two. The current meter rates still do not accomplish this, and they haven’t gotten buy-in from the PPA on their preferred strategy of dynamic pricing, even on a conceptual level.

If on-street parking were more expensive, you might see more garages setting their prices to compete for short-term customers, leaving more short-term spaces open on the street. But the authors say none of the garage operators they spoke with even think about competing with curb meter prices.

“Of all the parking operators that were interviewed, none take the cost for on-street parking into account when setting their own prices. Because on-street parking is relatively underpriced it is almost always at full capacity, especially in the densest areas of Center City and, as such, drivers are often forced to park in a garage or lot to avoid lengthy or fruitless searches for on-street parking. Therefore, garage operators need only compete with one another and not with the price of metered parking.”

As such, private garages are left appealing primarily to commuters, and their pricing reflects this. Most garage pricing strongly favors all-day commuter parking over short stays. PCPC says this creates an additional incentive for commuters to drive into the central business district during peak hours, rather than take transit.

Private garage operators are of course free to structure their prices as they wish, but the implication of the report is that the city can tilt the business incentives facing private operators more toward short stays by charging the right price for curb parking.

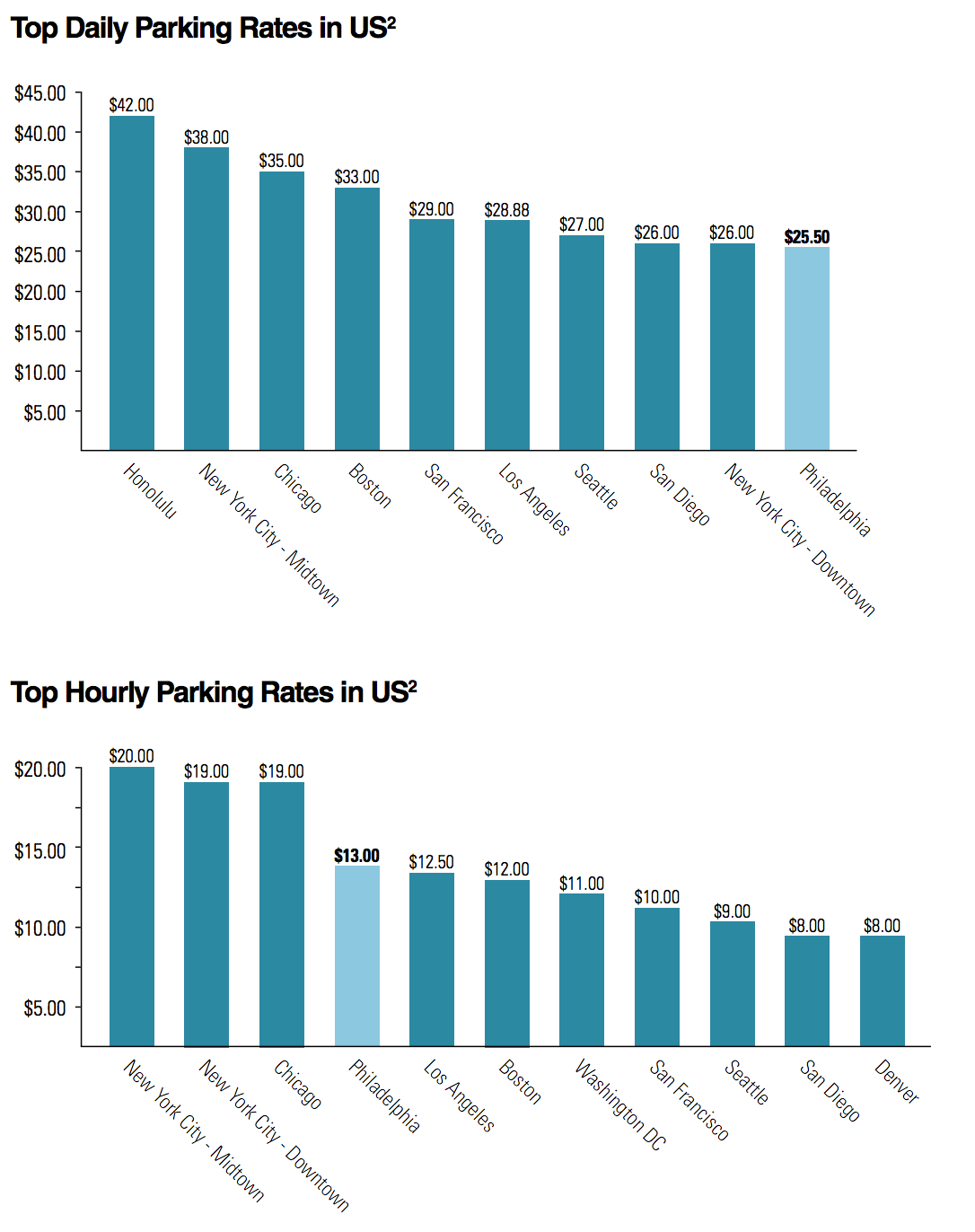

Naturally there’s disagreement over what the right price is, but many of our peer cities have been moving toward a definition based on occupancy, and that’s what the Planning Commission is recommending. Specifically, they recommend piloting a program like SF Park in San Francisco—a long-time Nutter administration goal that has gone unrequited despite appearing in every iteration of the Greenworks agenda—where prices are based on the conditions at the curb.

Many other cities have begun to transform their parking system with new technology. Los Angeles has implemented the LA Express Park TM program which uses new meters and parking space vehicle sensors to dynamically price on-street parking and mobile apps to allow drivers to locate available parking at the price they desire. The Seattle Department of Transportation has begun to adjust on-street parking rates to ensure balanced occupancy and space availability on every block throughout the city. We recommend that the City of Philadelphia consider a pilot program similar to SFpark that dynamically prices on-street parking to reflect demand and increases the use of public lots and garages as alternatives to metered parking.

As we explained in our article on dynamic parking pricing in Pittsburgh, the operating idea behind all these programs is that there is no one right price for curb parking. Because parking conditions are tighter and looser at different times of the day, maybe $3.50 is the right price to keep some curb spaces open during peak times, but $1.00 is the right price for off-peak.

In Pittsburgh, the early verdict on dynamic pricing is that it’s freed up more curb spaces, raised more net revenue, but lowered average prices.

Whether the Kenney administration will put their weight behind something like this is anyone’s guess, but as the report’s authors say, “as more surface lots and garages are taken out of service in favor of higher intensity uses, the management of the city’s parking resources will become increasingly critical” for a sustainable downtown economy.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.