Strict anti-hazing law signed in New Jersey

New Jersey joins Pennsylvania in having some of the toughest anti-hazing laws in the country after the death of a Penn State student from Central Jersey.

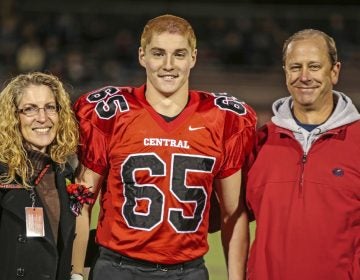

Gov. Murphy signed Timothy J. Piazza’s Law, requiring middle schools, high schools, and higher education institutions to adopt anti-hazing policies and clear penalties for violations. (Twitter / Gov. Murphy)

New Jersey joins Pennsylvania in having some of the toughest laws against hazing in the country.

Tuesday, Gov. Phil Murphy signed Timothy J. Piazza’s Law at Raritan Valley Community College in Branchburg, not far from where Piazza grew up in Hunterdon County.

The measure requires all public and private middle and high schools, as well as colleges and universities, to draw up anti-hazing policies, along with penalties for violations that could include withholding of a diploma, suspension, or expulsion.

The new law also establishes that hazing resulting in serious injury or death will be considered a third-degree crime, up from a fourth-degree. A conviction will carry a prison sentence of up to five years, a fine as high as $15,000, or both. Previously a hazing conviction carried a prison term of up to 18 months, a $10,000 fine, or both.

The law also bumps up hazing that results in injury from a disorderly persons offense — with a penalty of as much as six months of prison time and a $1,000 fine, or both — to a fourth-degree crime.

It also provides amnesty to anyone who provides help for the victim.

The law was prompted by 12-year-old Matthew Prager, Piazza’s neighbor and friend, who wrote to State Sen. Kip Bateman asking him to author anti-hazing legislation in Piazza’s memory.

“If a 12-year-old boy can recognize the difference between what is right and wrong, and what it means to be a friend and inclusive, we are hopeful that others will learn from this,” said Evelyn Piazza, Tim’s mother. “No young man or woman should ever be subjected to life-threatening behavior for just wanting to be included.”

Bateman was the lead sponsor of the law which passed both chambers of the Legislature in June unanimously.

Piazza, of Readington Township, died Feb. 4, 2017 from severe injuries after falling several times while being intoxicated as part of a fraternity ritual. Investigators concluded he had at least 18 drinks in under two hours. A security system recorded much of what happened before and after he fell down basement steps, had to be carried back upstairs, and spent the evening and ensuing night on a first-floor couch, showing signs of severe pain.

“Despite being in distress, none of the fraternity members were willing to help for fear of getting in trouble,” said Jim Piazza, Tim’s father, adding that hazing caused the family of four to become a family of three. “Some even prevented others from helping.”

Tim Piazza suffered severe head and abdominal injuries, but help was not summoned until the next morning. He died at a hospital.

“No parent should ever be concerned about sending their child off to college with his or her life or well-being put at risk just to join an organization,” said Jim Piazza. “It’s been four-and-a-half years since we’ve had the opportunity to see his smiling face, enjoy his magnetic sense of humor and receive one of his big bear hugs. Now, we only get to visit with him in our dreams.”

Tim Piazza’s death prompted Penn State to ban the fraternity involved, and Pennsylvania state lawmakers to pass legislation making the most severe forms of hazing a felony, requiring schools to maintain policies to combat hazing and allowing the confiscation of frat houses where hazing has occurred.

Jim and Evelyn Piazza have become anti-hazing advocates who also pushed for the Pennsylvania law.

Associated Press contributed reporting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.