Sperm provide next generation with more than just DNA, Penn study finds

It's not yet clear if the mechanism exists in humans, but it might be an important way that fathers influence their kids' risk of neurodevelopmental disorders.(Photo via ShutterStock)

Fathers might have more of a biological influence on their offspring than previously thought. New research from the University of Pennsylvania suggests it’s not only the genetic material in sperm that matters, but also tiny bits of RNA that fluctuate in response to stress.

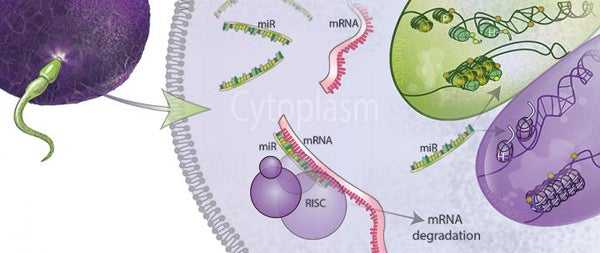

Known as microRNAs, they don’t code for proteins the way typical messenger RNA does. Instead, the molecules target other RNAs for degradation, altering the kinds of proteins available in cells.

In work published in the journal PNAS, Penn neuroscientist Tracy Bale and her team found that the microRNAs in mouse sperm go on to have a profound effect on the offspring’s brain.

The group identified the molecules after exposing male mice to stressful things such as predator odors or cage changes.

“We found nine specific microRNA in the sperm from dads that were stressed that were increased — significantly increased — by the stress experience,” said Bale.

When the researchers injected those microRNAs into newly fertilized eggs, brain development in the resulting babies changed. And when those mice grew up, they were less reactive to stress.

University of Pennsylvania researchers have shown at the molecular level how experiencing stress changes a mouse’s sperm in such a way that it affects its offspring’s response to stress. This change is imparted epigenetically, or through a means other than the DNA code, by molecules called microRNAs or miRs. (Image courtesy of University of Pennsylvania)

Bale said the findings illustrate a new mechanism for how paternal life experience is passed on to children. The results also force scientists to reject the long-held assumption that the environment doesn’t matter much for sperm.

“We’ve spent a lot of time thinking about mom, things that happen to mom while she’s pregnant,” she said. “We’ve really not given as much attention thinking about dad’s experiences.”

It’s not yet clear if the mechanism exists in people, but it might be an important way that fathers influence their kids’ risk of neurodevelopmental disorders. The Penn team plans to investigate sperm microRNAs in humans and look at their potential role in diseases such as autism.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.