Special Report: Salvation, optimism and perseverance in Eastern North Philadelphia

On June 3, 1993, Norma Morales and her three children woke up on a mattress on the floor of a drafty two-bedroom apartment in the Parkside section of West Philadelphia.

They were, as of that moment, officially homeless.

It had been a year since Morales and her kids left a comfortable house in Willingboro, N.J., forced out, she said, by an emotionally abusive relationship.

At first, her family took her in. Morales split time between relatives in Puerto Rico and her sister’s modest apartment in Philadelphia. During cold weather, when stateside, she and the kids would sleep in coats and gloves, huddling together to stay warm, as the frigid air blew in through an unfinished window.

Over the past several months, PlanPhilly has published a series of reports, this the last edition, on the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha and its role in Eastern North Philadelphia’s revival.

In 1998, John Kromer – then head of OHCD – led a city survey of abandoned properties in the area serviced by APM. Last fall, Kromer released a second survey of the neighborhood through the Fels Institute of Government at Penn. The survey examines what has become of the vacant lots he found in 1998. This PlanPhilly report leans heavily on Kromer’s findings.

The writing, video and photography that comprise this series was made possible by a grant from the William Penn Foundation.

By June, her family’s patience had worn out. Morales’ sister told her that she and the children needed to go. It just wasn’t tenable, the sister said, for the four of them to sleep on the floor of her living room indefinitely.

Her sister told her to try squatting, to find an abandoned home somewhere and claim it as her own. And Morales might have done it, were it not for a friend who had already tried it, only to find that the rats bit her children at night.

In desperation, as a very last resort, Morales sought out a homeless shelter. She had fallen so far. Years earlier, in Puerto Rico, she was a schoolteacher. She had two years of college. Checking into a homeless shelter was, for her, a shameful moment.

But it was also the moment that brought Norma Morales into the orbit of Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha.

The change agency

A non-profit development agency and social services provider, APM operates a constellation of programs designed to help troubled and low-income Philadelphians like Morales get back on their feet and, in time, become self-sufficient.

Mayor Nutter adjusts his glasses as he discusses the role CDCs play in neighborhood redevelopment.

The agency runs drug and alcohol rehab programs. If offers housing counseling. It manages health clinics and day care facilities. APM’s highest-visibility work is done by its community development corporation, which has built so many homes in Eastern North Philadelphia that the area, once desolate enough to be known as the badlands, has become a national model for urban redevelopment.

“CDCs are a critical component of neighborhood revitalization here in Philadelphia, I’ve felt that for a long period of time,” said Mayor Nutter, who called APM one of the city’s “premier” CDCs.

“When you look at what APM has done, with a number of other CDCs working in the same area … you will see complete revitalization taking place,” Nutter said.

Each year, APM provides direct aid and shelter to between 7,000-9,000 Philadelphians. The number is larger still when APM’s redevelopment work is taken into account, given its positive affect on property values, crime rates, and private investment in a neighborhood still badly in need of rebuilding.

This final PlanPhilly report on the remarkable reinvention of Eastern North Philadelphia focuses on three local families of different backgrounds. Their experiences illuminate the impact – direct and indirect – that APM and other community organizations have had on the lives of residents new and old in this rapidly changing neighborhood.

Watch an interview with Mayor Michael Nutter about the role that CDCs play. Story continues below….

From homelessness to home ownership

When Norma Morales is asked about APM, it takes only seconds before she starts to weep. Her story – her descent into homelessness, and her journey out of it – pours out of her in a torrent, interrupted only by sobbing.

“Going back to that spot, it’s almost like reliving it,” she said. “The heck with the marriage, the heck with everything, leave the house, I have to make a stand as a person, and when you start that …”

She breaks off, weeping again, and asks for more tissue.

When telling her tale, Morales speaks with remarkable precision. She effortlessly recalls specific dates, some decades in the past. They are momentous days – good and bad – that remain emblazoned in her mind.

On the day she left her sister’s apartment, June 3, 2003, Morales brought her kids to an APM-run shelter for women and children. She was expecting a house of horrors. Her family had warned her that, at shelters, “people get robbed, women get violated.”

What she found instead was a clean, well-equipped facility. She and her kids were given a large room, with a bed for each of them. Drawn together by crisis, she quickly bonded with the other women and children in the facility.

“We cooked together. We washed dishes together. We ate at a long table together. It was like a family,” Morales said.

Norma Morales, brushing her hair inside of her Pradera II style townhome which she purchased from APM.

She was there for less than five months (“four months and 25 days,” as she precisely puts it). But for Morales, it was a transformative period. At the shelter, she began helping out other residents with limited English-speaking abilities navigate the city’s bureaucracy. That morphed into volunteer work for APM, which in time she turned into a full-time, paying job in APM’s mental health division.

Even as she provided services to APM clients, Morales continued to receive help from the organization. The apartment she and her kids lived in was built and run by APM, and agency counselors worked with her for years to get her financial affairs in order.

One day at work in 1997, APM’s then-executive director Jesus Sierra came up to Morales’ desk and told her there was a job opening for a bi-lingual clerk in the office of the City Council President John Street. He encouraged her to apply.

Norma Morales, who had been homeless less than four years earlier, got the job.

She is still with the city today, serving as a constituent services representative in Councilman Darrell Clarke’s office, and earning a solid middle class salary. Her days there are often spent helping people not unlike her old self get access to city services.

“It’s a great feeling of accomplishment,” Morales said.

On March 19, 2007, Morales notched another accomplishment. She became a homeowner. With APM’s help she had repaired her credit and managed to sock away enough for a down payment on an APM built home.

Her suburban-style five-bedroom home is jam packed. Morales’ kids still live with her, including her youngest daughter, who is an undergraduate at Temple University.

And now Morales is in a position to help others as she was helped for so many years. She shares her home with a niece and her two young children as well, until they can get back on their feet.

The niece, Morales said, is the daughter of the same sister who told Morales to get out of her living room way back in 1993.

“I never thought any of this would happen. I thought I was just going to be another statistic, living in PHA or under section 8,” Morales said.

“You have to believe in you. And you have to give others the chance to help you. Some people say, ‘I don’t want that person helping us, I don’t want them all up in my business, but if you don’t let someone like APM help you, if you don’t help yourself, then you might as well just sit there.”

See a day in the life of Norma Morales. Story continues below….

Out of industry’s ashes, art and culture

Five blocks away from Norma Morales’ filled-to-bursting abode, Catherine Leigh Birdsall and Ben Riesman have made a home for themselves in a cavernous structure called the Maas Building.

Erected in 1859, the building’s history tracks that of Eastern North Philadelphia’s. It was a brewery, once, then a trolley repair shop, and later a copper smelter. As industry fled Philadelphia, the building took on another use as a kind of architectural graveyard, a repository for antique moulding, stone archways, old lumber and other building materials salvaged from crumbling homes across the city.

Three years ago, after moving to Philadelphia from Oakland, CA, Birdsall and Riesman stumbled across the Maas Building and fell in love with it. They topped the asking price, and in short order began creating a radically new identity for this Gilded Age relic.

“You see these buildings, and they’re decaying, but they’re beautiful. I think if you’re a certain type of person, you see the potential and not the decay,” said Birdsall, 34, who recently began working for the City of Philadelphia as a nurse.

Ben Riesman, co-owns the Maas Building with his wife, which is located on1320 N. 5th street in lower eastern north Philadelphia.

“There’s not that many places in the world where you can actually afford to buy a place like this and do whatever you want with it. They’re really interesting spaces, they’re really unique spaces.”

There is no question that – after depleting their savings, hitting their family members up for loans and pouring untold hours of sweat equity into the facility – Riesman and Birdsall have made the Maas Building into a truly unique space. It is part arts venue, part recording studio, part urban farm, part loft apartment and part office building, though much of it remains a work in progress.

Their renovations meld the building’s old but brutally handsome industrial features with modern touches like radiant floor heating. Somehow it all works, and the Maas Building is becoming a popular venue for small scale events ranging from weddings, to film screenings, to dance company rehearsals to live arts performances.

Last weekend, for instance, the Maas performance space was packed out for a show called “As The Eyes of The Seahorse,” which was billed as a “live indie-rock concert fused with immersive choreography.”

Unlike Norma Morales, Birdsall and Riesman have had no direct contact with APM, apart from shopping in a grocery store that the non-profit lured to the neighborhood 20 years ago. They do not rely on APM’s social services, nor do they rent or own an APM-built home. Indeed, the Maas Building lies a block to the southeast outside APM’s official redevelopment zone, which extends roughly south to north from Jefferson to York, and east to west from 4th to 9th Street.

But Birdsall and Riesman have nonetheless benefited from APM’s work, as well as that of other community development corporations active in the area, such as New Kensington and the Women’s Community Revitalization Project, both of which have contributed to Eastern North Philadelphia’s accelerating recovery.

Though they consider themselves relatively hardy urbanites, Birdsall and Riesman acknowledge they would not have moved so willingly, and invested everything they had, into a neighborhood that was all that much worse off than their own. The fact that there were organizations actively working to improve the area mattered to them.

“I don’t think I would go to some of the neighborhoods in Detroit or Baltimore that still look like this place did 20 years ago and do what we’ve done here,” Birdsall.

To be sure, the neighborhood remains rough. They have been burglarized, and neighbors told them someone was shot on their block this winter. When a contractor was repairing their roof, he found a loaded gun and, bizarrely, a large black dildo.

One of their more prosaic problems with the neighborhood is the lack of city services.

“I think of this neighborhood as embodying DIY, in all the good ways and the bad ways,” said Riesman, a musician and adjunct professor with Temple’s Tyler School of Art who hosts a monthly singer-songwriter show at L’Etage. “We basically have become responsible for a trash can the city doesn’t empty on our street. We’ve planted trees all around the area. I’m considering trimming the trees in the rec center because the city doesn’t do it and they’re dying. We regularly pick up tons of trash blowing around the streets.”

But for all the crime and blight that remains, Birdsall and Riesman know that the neighborhood they found in 2008 was more stable and more promising then it had been in decades.

Clearly, the rapid redevelopment (and accompanying gentrification) of Northern Liberties and Fishtown has had a lot to do with that. But would those neighborhoods have developed so quickly if the blocks further north remained as devastated as they were in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s?

Rose Gray, head of APM’s CDC, contends that the answer is no.

“Northern Liberties is growing. Temple University is growing phenomenally. But what if our area, east of Broad, never developed, would that still have been the case?” Gray said. “With all the wonderful things Temple is doing, with all the investment in Northern Liberties, our community needed to stabilize for those communities to grow.”

Gray’s point is that neighborhoods are connected, and that the ills of one – particularly a neighborhood as sick as APM’s was in decades past – can infect other nearby communities. Conversely, as APM slowly stabilized the formerly desolate blocks north of Jefferson and east of 9th Street, the organization made the neighborhoods of Northern Liberties and Temple more attractive to private investors, from mega-developers like Bart Blatstein to individuals like Riesman and Birdsall.

With few exceptions, Riesman and Birdsall said they had been made to feel welcome by their neighbors, which they described as a multi-cultural cast of characters including a guy with bullet holes tattooed on his neck who likes to park his lovingly maintained white Chevy SUV on the Maas Building’s well-lit sidewalk.

For the first few years, as the couple labored away renovating the inside of the warehouse, the neighbors were in the dark as to how much effort and money Riesman and Birdsall were pouring into the building. When they finally moved outside to do some façade work, Riesman found he was nervous about how his neighbors, most of them long-time residents, would react.

“These old time Puerto Rican dudes, they’d come out and look at us on the scaffolding and they’d say, ‘you guys are doing a great job man, it looks great,’ and we were like, ‘phew,’ because it could have gone the other way,” said Riesman, who speaks Spanish, as does his wife.

“We have just fallen totally in love with this building and this neighborhood, and we see this as a very long term investment,” Birdsall said.

Redevelopment yields appreciation, but also apprehension

Joseph Wanamaker’s investment in Eastern North Philadelphia is generations deep.

Neighborhood names are a fluid thing in this part of the city. Riesman and Birdsall think of themselves as residents of New Kensington. Norma Morales is closer to the part of town that some call Fairhill.

But as far as Wanamaker is concerned, they all live in Ludlow, a word he pronounces with a hard accent on the first syllable. “LUDlow.” When asked what his background is in the neighborhood and how long he has lived there, he replied without missing a beat:

“Ludlow is me.”

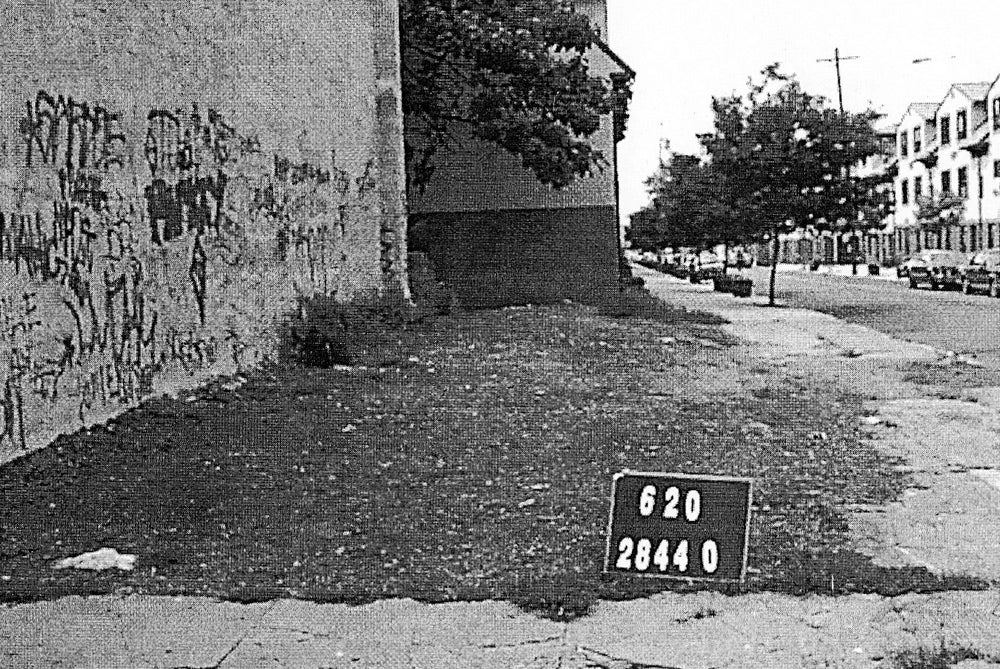

A PHA development now covers this lot at 637 W. Oxford St., which sat vacant at the time this photograph was taken in 1998.

Wanamaker, 54, is among a relatively small number of Ludlow residents who stayed behind and survived the neighborhood’s darkest decades, a period when many better off residents fled the area as North Philadelphia’s manufacturing jobs dried up.

He was born and raised on the 1600 and 1700 blocks of Marshall Street, and he now lives a stone’s throw away in an aging two-story rowhome on the 1600 block of N. 6th Street, where he and his wife raised five kids. The block is a rarity for the area, given that it’s occupied mostly by long-time residents in original rowhomes. It’s a slice of the old Ludlow, surrounded by block upon block of new suburban-style townhomes, constructed mostly by PHA and APM.

For a stretch in the early 1980s that lasted just two years, Wanamaker left Ludlow, settling with his wife in Northeast Philadelphia. But Ludlow pulled him back. That was partly because Ludlow’s proximity to Center City made it easy for Wanamaker to get to the doctors he must visit to treat his sickle cell disease. But mostly, he said, it was because Ludlow just feels like home to him.

“Ludlow was a community of people unified in the sense of helping one another, people looking out for one another. That’s the kind of community that Ludlow has always been and still is,” Wanamaker said.

As a community leader, Wanamaker is in frequent contact with APM on matters big and small. But he has never lived in an APM home, nor is he a client of any of APM’s social programs. What APM has done for him, Wanamaker said, is to help prevent the unrestrained gentrification of Eastern North Philadelphia by building so many housing options for low-income residents.

“If it wasn’t for them, there would be condos all around here,” Wanamaker said.

Gentrification has been a pressing concern for long-time residents of Eastern North Philadelphia for years. For the most part, those fears have been misplaced. Given the enormous tracts of vacant land and abandoned buildings that existed throughout the area, the development that has occurred has displaced very few long-time residents.

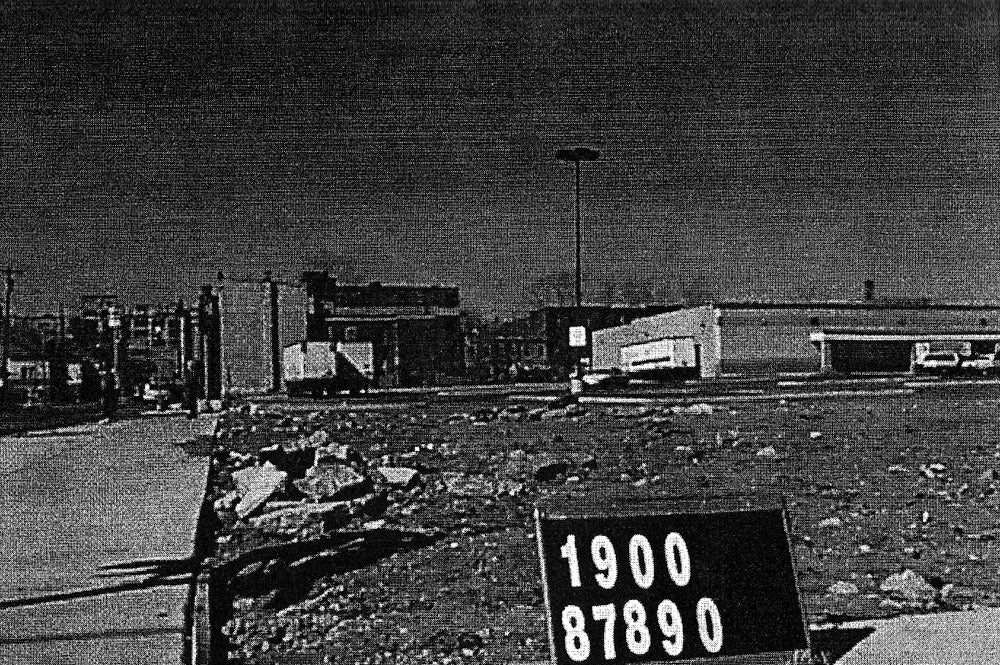

A PHA development covers a formerly vacant lot at 1906 N. 8th St.

Indeed, in a lot of ways what has happened in Eastern North Philadelphia to date has been a story of neighborhood recovery with little to no gentrification side effects. That hasn’t been the case in most other recently revitalized city neighborhoods, particularly Southwest Center City.

But as development ramps up as the economy improves, that storyline could change, and quickly. For instance, last year, just a half block north of Wanamaker’s house at the intersection of 6th and Cecil B. Moore, a 32-unit loft apartment complex opened up in an old factory. The owners are asking $1,200 a month for a two-bedroom unit in a building that was covered in wildly overgrown ivy and sported cinderblocks for windows as recently as 2009.

Wanamaker is hardly surprised. His father always told him that Ludlow would eventually redevelop. It was just too close to Center City not to, his father said. The Wanamakers believed in Ludlow’s future so strongly that Joseph now has an ownership stake in three homes in the neighborhood.

That means gentrification ultimately could pay off handsomely for Wanamaker, who said he routinely gets offers on the homes he owns. But he is nonetheless leery of what it will mean for the community he identifies with so strongly.

“Way back in the 60s and 70s, Ludlow was more of an African American and Latino community. Now with the new growth you have a multicultural community, and you have people who have a little more income,” Wanamaker said. “As long as everybody has an understanding that this is a mixed community, that’s good. Wealth can stabilize the community. But we don’t want to be overrun by wealth and forced out.”

APM agrees.

“There’s an appetite now for private investment. That’s not a bad thing, but you have to manage the economic changes, make sure there are options for people of different incomes,” Gray said.

Much more to come

The very fact that Wanamaker’s concerns now sound reasonable is itself a sign of how much Eastern North Philadelphia has changed. In 1990, when Gray first began her work at APM, she would stand at the intersection of 6th and Berks Streets and look upon acre after acre of wildly overgrown abandoned lots and long-empty homes.

Gray would be the first to say that too much blight remains. But she is proud of what APM has already accomplished, and excited about the projects the agency has line up for the future.

Late this year, construction is slated to begin on the non-profits most ambitious project yet, a mixed-use transit oriented development in the shadow of Temple University at 9th and Berks Streets. After that, there are rough plans for a senior-friendly apartment complex at 3rd and Berks that APM hopes will double as a greenway that buffers the neighborhood from industrial American Avenue. And the non-profit is in the middle of a comprehensive overhaul of its neighborhood plan, a process that is being funded and guided by the Local Initiatives Support Corporation.

“We think our best days are ahead,” Gray said.

Contact the reporter at pkerkstra@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.