Spanish immersion keeps growing in Delaware elementary schools

More than one in six Delaware public school kindergartners are enrolled in Spanish immersion, and more schools are interested in starting programs.

At Lewis Elementary School in Wilmington, fifth graders Rebekah Wright and Makayla Albino can converse in both Spanish and English.

The girls are among the growing number of participants in one of Delaware’s biggest education experiments in recent years: intensive learning in two languages, starting in kindergarten.

Begun six years ago under then Gov. Jack Markell, today about 4,000 kindergarten through fifth-grade students learn in Spanish and English. Another 1,000 do so in Chinese.

Spanish immersion is thriving in 26 elementary schools, plus two New Castle County charters. This year, more than one in six Delaware public school kindergartners are enrolled in Spanish immersion, and more schools are interested in starting programs.

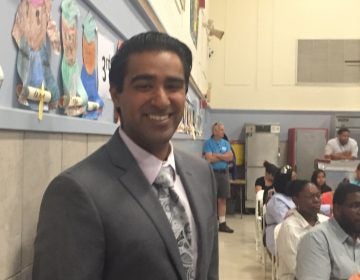

Marks Phelps, principal at Lewis, said he stresses to families how beneficial language immersion is for the students.

“Any time I talk to our parents, prospective parents that come in, the first thing I say is, ‘This is giving your child a gift,'” Phelps said.

“To be able to have students show by the end of their academic career that they are bilingual, not just bilingual, but biliterate and bicultural, and have a sense and appreciation of language and the power that it has and the cultural capital that it carries and the advantages it has for the workforce.”

At the traditional schools in Delaware with immersion programs, students spend half the day in each language. The charters, Las Américas ASPIRA and Antonio Alonso, do one full day in Spanish and the next in English.

ASPIRA, which is now in its sixth year at a sparkling former sports training warehouse near Newark, has expanded to middle school and is considering starting a high school.

Principal Margie Lopez Waite said ASPIRA was started to help Delaware’s Latino population become fluent in English.

“But, ultimately, what we we’re able to create was a school that was attractive not only to Hispanic families but to non-Hispanic families that also saw value in their children being bilingual and biliterate,” Lopez Waite said. “And in this day and age, regardless of whatever career pathway they pursue, it’s going to be an asset.”

Today, about 70 percent of ASPIRA’s students are native English speakers.

Lopez Waite said dual-language learning is critical for American society.

“We want to get to the point where when someone goes to the emergency room, they go see a doctor, they go into the pharmacy, they go into a school, they go into a supermarket, each one of those touchpoints in our community, it would be ideal to have somebody who is bilingual to make that individual feel welcome,” she said.

The dual-language classrooms work because teachers support each other, and so do the kids.

“When I see them in third grade, by that time, they have many of their basics down, their alphabet, their numbers and they can take content and connect it across languages,” ASPIRA teacher Diana Magana said.

“We just got a brand new student in our school. He’s from Puerto Rico and his English is limited, so it’s interesting to see those connections. They are practicing their Spanish, but he’s learning English along with them.”

Saniya Moore, an ASPIRA sixth grader, makes a daily 70-mile round trip from her home in Smyrna.

“It was a little hard but I really got used to it by the second grade,” Moore said.

State officials say the immersion program has exceeded expectations.

“In fifth grade, to be able to write a report in Spanish and English and then have discussions, and have this fluidity in two different languages, it sells by itself,” said Ana Richter, a Spanish immersion field agent for the state Department of Education.

“When you see parents and they do open houses and they walk through the building and they see this, like, who would not want that for their kid?”

Mike Pesce has three children at ASPIRA. His wife Serah volunteers, helping with outdoor gardens and office duties.

“So as much as our kids are learning Spanish, they are also picking up on cultural cues and they are going to be better adults, more compassionate adults, more well-rounded adults because they have friends who are from every kind of family situation, every kind of cultural situation that you could imagine,” Pesce said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.