Why SEPTA tracked away from European model

Feb. 16

By Anthony Campisi

For PlanPhilly

The news from SEPTA that it’s preparing to ditch the current regional rail numbering system is the final acknowledgement that a vision for the system created a quarter century ago has been abandoned.

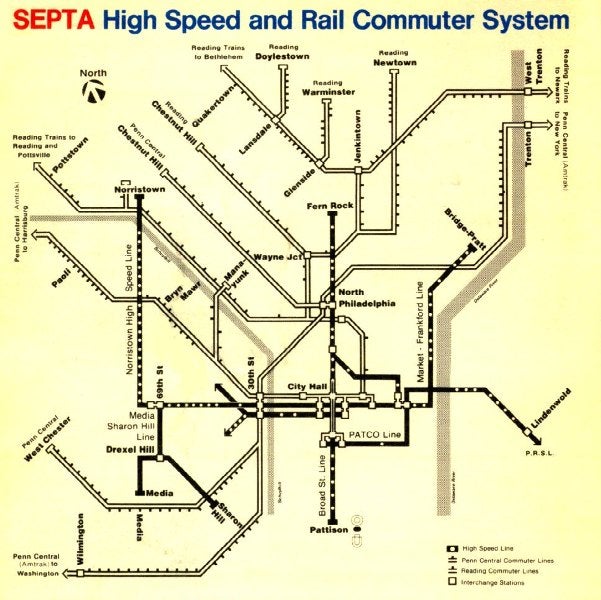

When the Center City Commuter Tunnel was opened in 1984, University of Pennsylvania engineering professor Vukan Vuchic sketched out a plan to bring S-Bahn service (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S-Bahn) to Philadelphia.

Instead of a traditional railroad service, trains would run every 15 minutes or so on all of the regional rail lines. Rather than attracting people willing to set their commutes according to SEPTA timetables, the authority would be able to gain more riders by allowing people to show up whenever they wanted for service into and out of Center City.

SEPTA would be able to accomplish this because the tunnel connected the old Pennsylvania and Reading railroad networks. Trains could now easily continue on past Center City to outlying neighborhoods and suburbs instead of having to deal with a dead end.

A long decline

That type of service, which is found in European cities like Copenhagen and Berlin, never got off the ground in Philadelphia. Instead, years of deferred maintenance and under funding caught up with SEPTA almost immediately, as the federal government cut most of its operating subsidies to large transit agencies during the Reagan administration.

In a sign of things to come, weeks after the tunnel opened, the authority had to shut the Columbia Bridge near Temple University for emergency repairs, temporarily separating the network anew.

SEPTA also had to manage temporary shutdowns of the Chestnut Hill West line and part of the Media line.

Indeed, the system literally began shrinking as SEPTA abandoned service to West Chester in 1986 and Newtown in 1983 — though community activists are trying to get that line restarted (http://planphilly.com/septa).

Rather than ushering in SEPTA’s golden age, the two decades following the commuter tunnel opening were marked by continual funding crises. SEPTA would periodically threaten doomsday scenarios, like shutting entire lines, to get the money it needed to operate the system.

That created a situation in which there wasn’t enough money to maintain the system as it was, much less fashion an S-Bahn, said Matt Mitchell of the Delaware Valley Association of Rail Passengers.

He also argued that the no one foresaw the steep drop in gas prices that was coming, which convinced commuters to abandon trains in favor of their cars.

In its vision for transit in the year 2000, published around the time the commuter tunnel opened, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission envisioned that mass transit would become the dominant player in regional commuting, as high gas prices and a constrained energy supply forced people to abandon their cars in favor of trains — an assumption that featured heavily in the vision for S-Bahn service.

That didn’t happen, and only recently did high gas prices bring people back onto trains, though prices have since dropped thanks to the recession.

In fact, transit trips into Center City declined by 80,000 trips per day from 1980 to 2005. In contrast, car trips to Center City increased by 400,000 trips a day, according to a Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission traffic study.

With low gas prices and new highways — like the Interstate 95 segment by the airport — opening up Center City to the suburbs, people eschewed trains for the comfort of driving, said Scott Brady, head of the DVRPC’s office of travel modeling and author of the study.

Moving forward

SEPTA’s funding woes continued until 2007, when Act 44 provided a dedicated source of state funding to public transit for the first time. Now, the authority seems focused on improving service along the current regional rail model, and the decision to jettison regional rail numbers is further proof of that tactic.

Indeed, the decision is more akin to “making the unwritten rules written” because SEPTA stopped seriously discussing S-Bahn service long ago, according to DVRPC senior transportation planner Greg Krykewycz.

Incidentally, the one-seat opportunities that some fear will be endangered by the regional rail naming change didn’t feature in the original plans for the lines. With short headways envisioned by an S-Bahn, a one-seat ride through Center City wasn’t a major goal of the plan, Mitchell said.

Riders would instead be able to easily transfer in Center City for outbound trains.

Regional rail numbers were instead assigned instead to balance ridership on both sides of the lines.

But that plan never panned out. The R4 line, which would have run from Bryn Mawr through to Newtown, was abandoned and the lines had to be reconsidered. The regional rail system also shrunk — the Cynwyd line, for instance, originally terminated at Ivy Ridge — creating intra-line ridership and distance imbalances.

And though SEPTA general manager Joe Casey said in an earlier interview that he’d like to see half-hour headways on all lines, he said that he wasn’t looking to reduce train crew sizes — the key move needed to reduce operating costs enough on the rail side to support S-Bahn service frequency.

So instead of pushing for a return to the S-Bahn idea, which Mitchell argued is out of date and unrealistic given SEPTA’s funding situation, his group is instead calling on the authority to leverage upcoming changes to create a better customer experience along the lines of traditional railroad service.

The new Silverliner V railcars, coupled with smart card technology and infrastructure investment paid for by stimulus funds and Act 44 put SEPTA in a good position to rebrand the regional rail network to attract higher ridership, he said.

Viewed that way, the regional rail name change becomes part of a broader SEPTA effort at improving communication, from better signage to the authority’s popular Twitter account (http://twitter.com/septa), which provides riders with up-to-date service information.

And without the short headways envisioned by S-Bahn service, it’s probably not realistic to assume that SEPTA could capture a significant portion of the suburb-to-suburb commuter market that through-service advocates want to serve, Krykewycz said.

The current regional rail system does a good job bringing commuters into and out of Center City but isn’t nearly as efficient at serving suburban residents who commute to jobs in the suburbs, he explained.

A plan to provide such suburban-to-suburban service was included in a failed iteration of the Schuylkill Valley Metro project and would have used a light rail line to connect regional rail lines. (A schematic of this and other proposed SEPTA expansion projects can be found here [ http://septawatch.com/maps/single-gallery/4283147 ].

The DVRPC’s Brady also pointed out that few suburban rail stations are close to employment centers. Barring a wave of transit-oriented development, employers would either have to run shuttles or SEPTA would have to reconfigure its suburban bus routes substantially to bring workers from train stations to their jobs.

At the same time, the DVRPC hasn’t done a comprehensive study of suburb-to-suburb commuters that regional rail could serve under a new train routing system, so it’s possible, Krykewycz said, that new data could show a benefit of routing certain trains in new ways to capture more riders.

Contact the reporter at campisi.anthony@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.